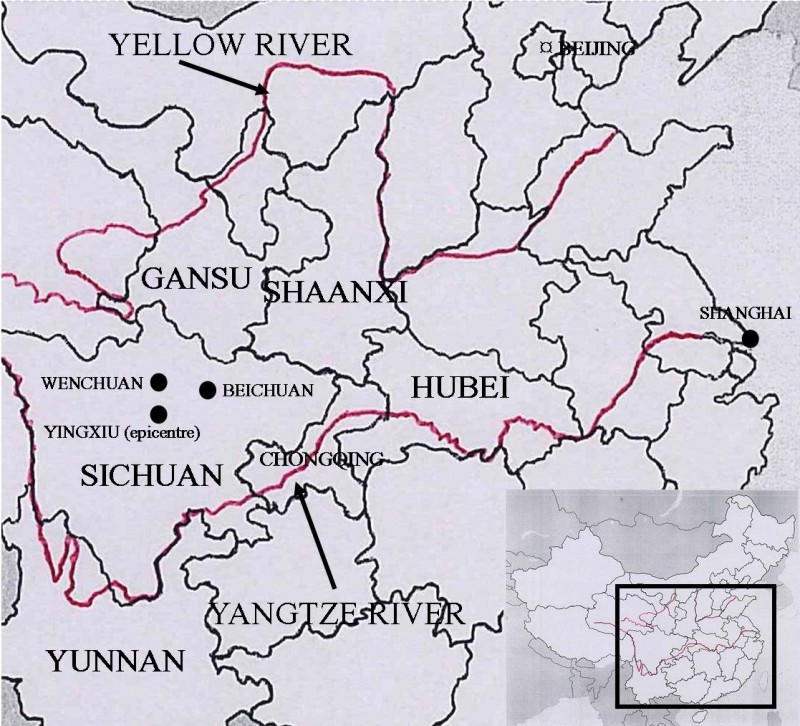

2008年5月12日,中國西南的四川汶川縣遭受8.0級地震,嚴重影響該省北部地區,以及鄰近的甘肅省和陝西省 。共有十個省份受到地震的破壞。甚至北京與上海也感受到地震。地震從下午2:28:01開始,震央在映秀鎮,深度為19公里。根據官方報告,受汶川地震影響的51個縣被歸類為 「嚴重」或「非常嚴重」。災情最嚴重的縣市,在地震當時加起來的人口約有四百萬人,遭受幾近徹底的破壞。受創最嚴重的地區主要由少數民族居住,位於山上的鄉村。多次的強烈餘震,山崩,土石流,堰塞湖(因山崩或土石流形成的河床,儲水後形成湖泊)以及惡劣的天氣狀況,使得救援行動備受挑戰。汶川地震共影響四千五百五十萬人的生活。

背景

離北京夏季奧運開幕典禮只有88天,發生汶川地震。一開始,讓人質疑中國是否能夠在重大災難發生不久後主辦這場國際競賽,但中國政府迅速向國際體育團體保證,所有的籌備工作將如期進行。2008年3月,由於奧運即將到來以及西藏發生鎮壓抗議,使得中國成為焦點。因為國際的關注提高,讓中國更加感受到有效處理災難以及強調國家團結的壓力。此外,在2008年稍早的時候,巨大的暴風雪襲擊華南地區,癱瘓交通並造成其他相關問題,中國政府為此受到強烈抨擊。這個暴風雪發生在最糟的時機,因為是在農曆春節期間,這時數百萬人要返鄉團圓。人民被困在火車站多天,而政府對此的反應,普遍被認為緩慢而沒有力道。[1]

2008年5月15日 英國廣播公司報導汶川地震的新聞剪輯。

Source: BBC, ‘China Sichuan Quake – BBC report,’ newsreel, May 15, 2008

雖然長期以來預測這個地區有可能發生大地震,但是對政府以及當地居民來說,汶川地震都讓人意外。長久以來大家都知道四川是地震活躍區,而板塊運動所在地的龍門山斷層具有不安定的歷史。[2]2004年,中國地震局指定甘肅 – 阿壩,包括龍門山斷層,作為地震監測與研究的危險區域。[3] 此外,四川省政府在2005年發佈了加強地震監測以及減災措施的計劃,以提高公眾的災害意識。[4] 該計劃特別強調透過以下方法來改善農村的安全:教育民眾抗震的建築工法,改善施工品質,改善水力發電設施的安全,更嚴密監督是否遵守都市的抗震建築標準。

2005年的地震監測計劃,還不清楚有多大的影響,但至少汶川和綿陽的地方政府已經開始進行地震測驗比賽,以教育公眾了解地震的危害。[5] 然而,儘管進行法律改革,但備災程度仍然不足,許多建築物都無法承受震動。 地震發生後,清華大學的研究小組與西南交通大學和北京交通大學合作展開建築物損壞調查,報告提到,許多建築物,特別是學校和工業建築,缺乏足夠的抗震能力。研究報告的作者是清華大學防災減災計畫研究中心的陸新珍教授,陸教授將原因歸咎於預防措施應用上的失敗。[6]

損害

根據2008年8月25日發布的官方記錄,死亡人數為69,226人,傷者為374,643人,失踪的17,923人被認定死亡。[7] 至少1500萬人撤離家園,500多萬人無家可歸。四川省、一部分的重慶、甘肅、湖北、陝西、雲南等地估計有536萬棟建築倒塌,2100多萬棟建築受損。整體的經濟損失估計為8000億元。北川,都江堰,烏龍,映秀幾乎全毀。山崩和落石損壞或毀壞北川汶川地區的幾條山路和鐵路,並且掩埋建築物,切斷進入該地區的通道達數天之久。[8]

災難反應

有關地震的消息,當局採取迅速的回應。在主震過90分鐘後,溫家寶總理飛到災區監督救援工作。[9] 地震當天,政府開始將物資送到災區,並動員大約13萬至14萬人民解放軍和準軍事警察到受影響的地區。政府部門、共青團這類大型的組織,以及中國紅十字會這類公益組織派送物資和搜救隊,並且透過國家網絡來動員志工和資金。地震發生一周後,四川省共青團估計在地震區大約有20萬名志工。[10] 共青團和紅十字會能夠迅速取得在災區工作的許可,為救災工作籌集資金,但缺乏有效利用資源的工作人員。[11]

災難發生後當下,媒體被允許以非常開放的方式從災區報導,有一段時間,甚至發表非常批判性的報導。[12] 這個相當開放的情況為時短暫,是中華人民共和國首度讓媒體熱烈地接觸到大規模的災難和苦難的場景,這種經歷使大眾普遍產生對罹難者和生還者的同情。個人、公司和民間社會組織自發性的藉由捐款、捐血和捐贈貨物來幫助災民。許多志工還進到災區協助救援工作,而當地的計程車司機則提供重要的交通管道。[13] 即使中國當局抱持懷疑的態度來看待非政府組織,但汶川地震過後不久,卻暫時放寬了法律限制。不過,非政府組織和非正式的團體仍然遭遇到當局的刁難。[14] 儘管面臨挑戰,志工和基層組織在救援工作中發揮了重要的作用,即使他們這類任務的經驗不足,偶爾會招致批評,而讓他們參與救災的這個機遇其實是相當短暫的。需求幫忙的規模遠遠壓過當局處理這種情況的能力,而且除此之外,受創最嚴重的地區其當地的國家機關受到嚴重破壞。[15]

政府對汶川地震的處理反應很快,尤其是與1976年唐山地震或2008年年初的暴風雪相比。例如,理查德·蘇特邁爾認為,與上述災害相比,反應時間良好,中央各部門之間的機構協調、以及中央各部門和地方當局之間的協調都相當有效,信息管理有所改善,民間的社會行動者有機會參與響應。[16] 然而,問題並不罕見。平民領袖和軍事領袖間的指揮鏈存在著問題; 欠缺必要的設備,如帳篷和防水布; 備災水平不足; 腐敗阻礙重建。[17] 此外,由於道路封閉和專業救援隊數量不足,有好幾天的時間外界無法進入幾個偏遠和分散的村莊。[18]

重建工作

在「汶川地震後修復和重建總體規劃」中,總成本估計為一兆元。[19] 災區各省級政府負責執行災後修復和重建工作。另一方面,地方(鄉,村/社區)政府的任務是分配補償金和建造住所。縣級以上政府被要求募款做為修復和重建之用,募款的方法如政府投資、一對一援助、社會集資、和市場運作等。[20]

2008年5月,中央電視台新聞剪輯報導汶川地震。

Source: CCTV, ‘CCTV report of Sichuan earthquake,’ newsreel, May 12, 2008

官方設定的目標是在2010年9月完成住房重建,但根據CASTED(中國科學技術發展研究院)和挪威法福應用國際研究所進行的調查,受調查的住戶有0.6%仍然住在2011年夏天搭建的帳篷或其他的臨時房屋。[21] 需要修理或重建家園的家庭獲得現金補貼,低利率貸款和免稅,但家庭儲蓄仍然是最重要的資金來源,特別是那些需要購買或重建房屋的民眾。在必須修屋或買房的家庭中,有80%獲得政府補助。政府補助約占城鄉修補費的40%。然而,必須重建或購買新房的農村家庭所獲得的政府補助僅有26%,而城市地區只有12%。[22] 大多數農村家庭靠自己或者在縣[23] 和地方層級的政府指導下重建房屋,然而城市家庭比較可能收到新房子,新房可能是特別打造的替代品或新添購的屋子。[24]

即使四川省政府要求對所有受影響的房屋接受評估,並在修復和重建過程中採取防震措施,但這些政策沒有妥善地具體實施。挪威法福和中國科學技術發展研究院所做的調查發現,2011年重建工作完成之後,調查區只有43%的家庭(N = 3754戶)居住在採用防震措施來強化的房屋。新建或新購的房屋則情況較好,其中75%(N = 1500戶)符合抗震建築標準。[25]

災難政治學

汶川災難期間和之後,國家的政治宣傳強調共產黨的高效率領導和人民解放軍英勇的救援工作。民族團結和平民百姓無私的英雄主義也是官方論述的重要主題。然而,一些消息卻質疑這些強調援救的積極面的敘述,該消息提到數千名學生葬身在劣質的學校建築物中。確切的罹難學生人數不得而知,而且數字不同,官方公布的死亡人數為5,335人,而路透社在災後不久公布的估計死亡人數高達9000人。這個估計是根據新華社和當地媒體報導所公布的數據。[26]

學生家長、環保人士譚作人和藝術家艾未未等人針對災難的各個方面進行獨立調查,包括學校的塌陷和學生的死亡,此外,四川省地質礦產局總工程師肖曉還發表文章,聲稱大紫坪舖水庫可能增加該地區的不穩定性,引發地震,但是這項理論,充其量只是個假設而已。然而,它卻關連到政府責任和四川水力發電計畫的爭執等敏感的問題,這就是為什麼這個話題在中國會受到審查。[27]

作者:MarjaanaMäenpää是芬蘭圖爾庫大學哲學、當代歷史與政治學系的博士候選人。

翻譯: 邱奕齊

注釋

[1] Xu, Bin (2012): “Grandpa Wen: Scene and political performance”. Sociological Theory, 30(2), p.124.

[2] Qian Gang (2009a): “Learning our hard lessons from Sichuan’s March 2008 earthquake quiz competitions”. China Media Project blog. May 12. <http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/12/1608/>. [Accessed January 27, 2016.] For example, Beichuan suffered from M 6.2 earthquake in 1958 and in 1976 quakes took place at Songbo and Pingwu.

[3] Zhang, Peizhen: “十一届全国人大常委会专题讲座第四讲中国地震灾害与防震减灾”. Published on the website of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. <http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/xinwen/2008-06/30/content_1435752.htm>. [Accessed February 1, 2016.]

[4] Sichuan zhengbao (2005): ”四川省人民政府关于进一步加强防震减灾工作的通知”. 川府发[2005]6号. January 31.<http://www.sc.gov.cn/sczb/lmfl/szfwj/200706/t20070608_185659.shtml>. [Accessed February 1, 2016.]

[5] Qian 2009a.

[6] China Media Project: “A news story on school collapses tantalizes, then disappears”. May 26, 2009. http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/26/1641/. [Accessed March 2, 2016.] The news story on the research originally appeared in China Economic Weekly and was reposted by China Media Project.

[7] Xinhua: ”权威发布:四川汶川地震抗震救灾进展情况”. August 25, 2008. <http://news.xinhuanet.com/newscenter/2008-08/25/content_9707753.htm>. [Accessed January 28, 2016.]

[8] US Geological Survey: “M7.9 – eastern Sichuan, China”. <http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/usp000g650#general_summary>. [Accessed January 18, 2016.]

[9] China.com.cn: ”5.12四川汶川7.8级地震日志:5月12日”. May 17, 2008. <http://www.china.com.cn/news/txt/2008-05/17/content_15287221.htm>. [Accessed January 29, 2016.]

[10] GONGO = Government organized non-governmental organization. Shieh, Shawn & Deng Guosheng (2011): “An emerging civil society: The impact of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake on grassroots associations in China”. Research report. The China Journal, 65, p. 185.

[11] Xu, Bin (2014): “Consensus crisis and civil society: The Sichuan earthquake response and state-society relations”. The China Journal, 71, p. 95.

[12] The Central Party Propaganda Department forbade sending journalists to the quake zone but this verbal ban was made obsolete by the Central Politburo, who instructed the Xinhua News Agency and China Central Television to report on the disaster in “timely, accurate, open and transparent” manner (Xu 2012, p. 120). Nevertheless, the Central Propaganda Department prohibited the detailed reporting on school collapses on May 15, but in practice the ban was enforced only in June. Before that, several critical articles were published and even though most of them appeared online, they there published by established commercial media outlets such as Southern Metropolis Daily and Southern Weekend and even by Party mouthpieces, such as People’s Daily and Xinhua. (Bandurski, David (2008):, ‘中国媒体大地震’ (The great earthquake of Chinese Media). Wall Street Journal China Online, May 29. <http://chinese.wsj.com/gb/20080529/opn091318.asp?source=email>. [Accessed 15 May 2014]; Qian, Gang, (2009b): “Looking back on Chinese media reporting of school collapses”. China Media Project blog, May 7. http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/07/1599/. [Accessed 15 May 2014.])

[13] Xu, Bin (2009): “Durkheim in Sichuan: the earthquake, national solidarity and the politics of small things”. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72(1), pp. 5 – 8; Paik, Wooyeal (2011): “Authoritarianism and humanitarian aid: regime stability and external relief in China and Myanmar”. The Pacific Review, 24(4), pp. 439 – 462; Xu 2012, pp. 120 – 121.

[14] Roney, Britton (2011): ”Earthquakes and civil society: A comparative study of the response of China’s nongovernment organizations to the Wenchuan earthquake”. China Information 25(1), p. 86; Xu 2014, pp. 98 – 99.

[15] Xu 2014, p. 94.

[16] Suttmeier, Richard P. (2011), “China’s management of environmental crises”. In Jae Ho Chung (ed.), China’s Crisis Management. Routledge, p. 116.

[17] See for example. Suttmeier 2011, pp. 116–117; Yang, Jun et al (2014): “Comparison of two large earthquakes in China: the 2008 Sichuan Wenchuan Earthquake and the 2013 Sichuan Lushan Earthquake”. Natural Hazards, 73, p. 1130.

[18] Suttmeier 2011, 117; Xu 2014, p. 94.

[19] Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China: ”汶川地震灾后恢复重建总体规划”. 国发〔2008〕31号. September 23, 2008. <http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2008-09/23/content_1103686.htm>. [Accessed February 1, 2016.]

[20] The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: “Regulations on Post-Wenchuan-Earthquake Restoration and Reconstruction”. Order of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Order No. 526. June 8, 2008. http://www.sc.gov.cn/10462/10758/10759/10764/2012/7/26/10219700.shtml. [Accessed March 3, 2016.]; Dalen, Kristin, Hedda Flatø, Liu Jing and Zhang Huafeng (2012): Recovering from the Wenchuan Earthquake: Living Conditions and Development in the Disaster Areas 2008-2011, Fafo-report, 39 p. 174.

[21] Dalen et al (2012), p. 43. The first round of survey took place soon after the earthquake in 2008 (n=3652 households), the second one year later (n=4015 households), and the last three years later in the summer 2011 (n=3841 households).The final report (Dalen et al) was published in 2012. The stated purpose of the first survey was to provide Chinese authorities information on the circumstances and needs of the people living in the disaster area, while the second and third survey aimed at assessing the implementation of reconstruction plan and its impact on the affected households. Survey design, sampling methods and fieldwork are explained in the final report, Dalen et al (2012), pp. 15-16.

[22] Dalen et al (2012), pp. 36-37, 43-44.

[23] The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: “Regulations on Post-Wenchuan-Earthquake Restoration and Reconstruction”.

[24] Dalen et al, p.43.

[25] Dalen et al., p. 49.

[26] The Guardian: “China releases earthquake death toll of children”. May 7, 2009. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/may/07/china-earthquake-anniversary-death-toll>. [Accessed January 15, 2016.] Chen Min, ‘[重建之思] 真相比荣誉更重要——林强访谈录’ ([Thinking about reconstruction] Truth is more important than glory – the record of the interview with Lin Qiang). Southern Weekend, 30 May 2008. <http://www.infzm.com/content/12753>. [Accessed May 14, 2014.] Sichuan province’s own investigation report stated that there were five reasons for the collapse of schools: the earthquake surpassed the forecasted strength; the quake struck at a time when classes were still on; third, the classrooms and corridors, where the most students were, were weakly connected; the buildings were old-fashioned and backward; and the design of anti-seismic elements in the construction had some innate flaws. However, the sheer force of the quake was considered to be the main reason for destruction.

[27] Roney 2011, pp. 89-90.

資料

Bandurski, David (2008):‘中国媒体大地震’ (The great earthquake of Chinese Media). Wall Street Journal China Online, May 29. <http://chinese.wsj.com/gb/20080529/opn091318.asp?source=email>. [Accessed 15 May 2014]

Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China: ”汶川地震灾后恢复重建总体规划”. 国发〔2008〕31号. September 23, 2008. <http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2008-09/23/content_1103686.htm>. [Accessed February 1, 2016.]

Chen Min, ‘[重建之思] 真相比荣誉更重要——林强访谈录’ ([Thinking about reconstruction] Truth is more important than glory – the record of the interview with Lin Qiang). Southern Weekend, 30 May 2008. <http://www.infzm.com/content/12753>. [Accessed May 14, 2014.]

China.com.cn: ”5.12四川汶川7.8级地震日志:5月12日”. May 17, 2008. <http://www.china.com.cn/news/txt/2008-05/17/content_15287221.htm>. (Last visited January 29,

2016.)

China Media Project: “A news story on school collapses tantalizes, then disappears”. May 26, 2009. http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/26/1641/. [Accessed March 2, 2016.]

Dalen, Kristin, Hedda Flatø, Liu Jing and Zhang Huafeng (2012): Recovering from the Wenchuan Earthquake: Living Conditions and Development in the Disaster Areas 2008-2011, Fafo-report, 39.

Paik, Wooyeal (2011): “Authoritarianism and humanitarian aid: regime stability and external relief in China and Myanmar”. The Pacific Review, 24(4), pp. 439–462.

Qian Gang (2009a): “Learning our hard lessons from Sichuan’s March 2008 earthquake quiz competitions”. China Media Project blog. May 12. <http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/12/1608/>.

Qian, Gang, (2009b): “Looking back on Chinese media reporting of school collapses”. China Media Project blog, May 7. http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/07/1599/. [Accessed 15 May 2014.]

Roney, Britton (2011): ”Earthquakes and civil society: A comparative study of the response of China’s nongovernment organizations to the Wenchuan earthquake”. China Information 25(1), pp. 83–104.

Shieh, Shawn & Deng Guosheng (2011): “An emerging civil society: The impact of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake on grassroots associations in China”. Research report. The China Journal, 65,

Sichuan zhengbao (2005): ”四川省人民政府关于进一步加强防震减灾工作的通知”. 川府发[2005]6号. January 31. <http://www.sc.gov.cn/sczb/lmfl/szfwj/200706/t20070608_185659.shtml>. (Last accessed February 1, 2016.)

Suttmeier, Richard P. (2011), “China’s management of environmental crises”. In Jae Ho Chung (ed.), China’s Crisis Management. Routledge, pp. 108–129.

The Guardian: “China releases earthquake death toll of children”. May 7, 2009. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/may/07/china-earthquake-anniversary-death-toll>. [Accessed January 15, 2016.]

The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: “Regulations on Post-Wenchuan-Earthquake Restoration and Reconstruction”. Order of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Order No. 526. June 8, 2008. http://www.sc.gov.cn/10462/10758/10759/10764/2012/7/26/10219700.shtml. [Accessed March 3, 2016.]

US Geological Survey: “M7.9 – eastern Sichuan, China”. <http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/usp000g650#general_summary> (Last visited January 18, 2016)

Xinhua: ”权威发布:四川汶川地震抗震救灾进展情况”. August 25, 2008. <http://news.xinhuanet.com/newscenter/2008-08/25/content_9707753.htm>. (Last visited January 28, 2016.)

Xu, Bin (2014): “Consensus crisis and civil society: The Sichuan earthquake response and state-society relations”. The China Journal, 71, pp. 91–108.

Xu, Bin (2012): “Grandpa Wen: Scene and political performance”. Sociological Theory, 30(2), 2012, pp. 114–129.

Xu, Bin (2009): “Durkheim in Sichuan: the earthquake, national solidarity and the politics of small things”. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72(1), pp. 5–8.

Yang, Jun, Chen Jinhong, Liu Huiliang & Zheng Jingchen (2014): “Comparison of two large earthquakes in China: the 2008 Sichuan Wenchuan Earthquake and the 2013 Sichuan Lushan Earthquake”. Natural Hazards, 73, pp. 1127–1136.

Yin, Liangen and Wang Haiyan (2010): “People-centred myth: Representation of the Wenchuan earthquake in China Daily”. Discourse & Communication, 4(4), pp. 383 – 398.

Zhang, Peizhen: “十一届全国人大常委会专题讲座第四讲中国地震灾害与防震减灾”. Published on the website of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. <http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/xinwen/2008-06/30/content_1435752.htm>. (Last accessed February 1, 2016.)