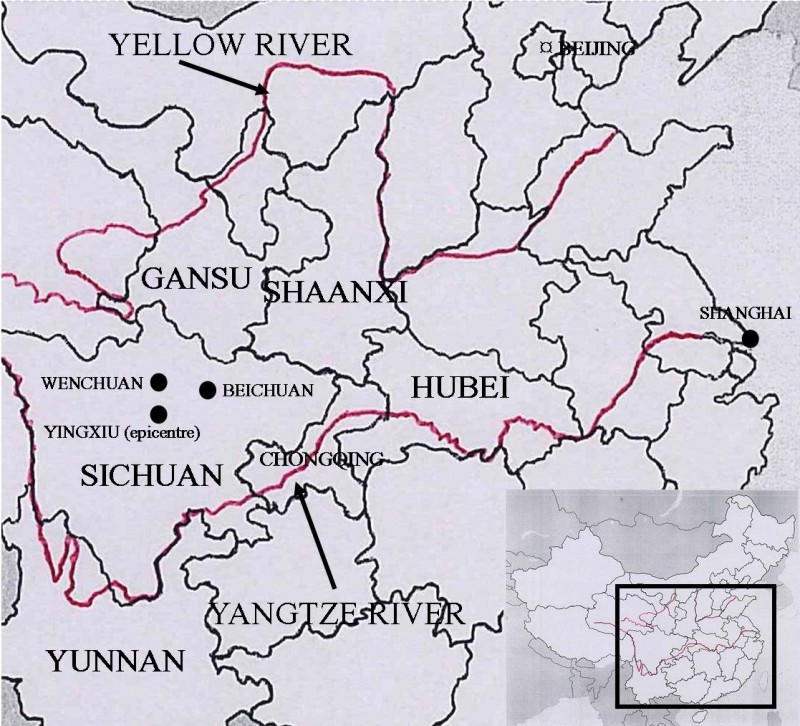

On May 12, 2008, Wenchuan county in Sichuan province, in Southwest China, was hit by an 8.0 magnitude earthquake that severely affected the northern areas of the province as well as some regions of the neighbouring provinces Gansu and Shaanxi. Altogether ten provinces suffered some damage as a consequence of the quake and the tremors were also felt in Beijing and Shanghai. The earthquake began at 2:28:01 p.m. and the epicentre, 19 km deep, was located in Yingxiu town. Officially, 51 counties were classified either “seriously” or “very seriously” affected by the Wenchuan earthquake. Most of the very seriously affected counties, whose combined population at the time of the disaster was approximately four million, suffered near-complete destruction. The hardest-hit communities were largely inhabited by ethnic minorities and located in the mountainous rural areas. Several strong aftershocks, landslides, mud-rock flows, quake lakes and bad weather made rescue and relief efforts even more challenging. Altogether, the earthquake affected the lives of more than 45.5 million people.

Context

The Wenchuan earthquake happened only 88 days before the opening ceremony of the Beijing Summer Olympics. At first, there were some doubts whether China would be able to host the games so soon after a major disaster, but the Chinese government rapidly reassured the international sporting community that all the preparations would proceed as planned. Because of the approaching Olympics as well as the suppression of protests that took place in Tibet in March 2008, China had been in the spotlight. This heightened international attention added the pressure for the government to effectively deal with the disaster and emphasize national unity. Moreover, the government had been sharply criticized earlier the same year, when a massive snowstorm hit Southern China, paralyzing the transportation and causing other related problems. The timing of the blizzard was the worst possible as it happened during the Chinese New Year holiday when millions of people travel to meet their families. People were stuck in train stations for days and the government’s response was widely considered slow and feeble.[1]

News reel clip of a BBC report on the earthquake, May 15, 2008

Source: BBC, ‘China Sichuan Quake – BBC report,’ newsreel, May 15, 2008

The Wenchuan earthquake came as somewhat of a surprise to both the authorities and the local residents, although there were long-term forecasts that a major earthquake would strike the area. Sichuan is long known to be a seismically active region and the Longmen Mountain fault, where the movements of the tectonic plates took place, has a history of restlessness.[2] In 2004, the China Earthquake Administration had designated Ganzi-Aba, including the Mt. Longmen fault, as a danger zone where earthquake monitoring and research should take place.[3] In addition, the Sichuan provincial government published in 2005 a plan to strengthen earthquake monitoring and disaster reduction measures and to increase public awareness of calamities.[4] The plan particularly emphasized improving the safety of rural communities through educating the public on earthquake-resistant building methods and improving the quality of construction as well as improving the safety of hydropower facilities and better supervision of the compliance with the anti-seismic construction standards in urban areas.

It is not clear how much effect the 2005 earthquake monitoring plan had, but at least in Wenchuan and Mianyang, local governments had started running earthquake quiz competitions in order to educate the public on seismic hazards.[5] However, despite all the legal reforms, the preparedness level was still inadequate and many buildings could not stand the tremors. After the earthquake, a research group from Tsinghua University launched an investigation on building damage in collaboration with Southwest Jiaotong University and Beijing Jiaotong University and they reported that many buildings, particularly schools and industrial structures, lacked the adequate level of seismic resistance. The author of the research paper, professor Lu Xinzhen of Tsinghua University’s Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Project Research Center, attributed this to the failure of application of preventive measures.[6]

Damage

According to official records released on August 25, 2008, the death toll was 69,226 people, while 374,643 were injured and 17,923 are missing and presumed dead.[7] At least 15 million people were evacuated from their homes and more than 5 million were left homeless. An estimated 5.36 million buildings collapsed and more than 21 million buildings were damaged in Sichuan and in parts of Chongqing, Gansu, Hubei, Shaanxi and Yunnan. The total economic loss was estimated at 800 billion yuan. Beichuan, Dujiangyan, Wuolong and Yingxiu were almost completely destroyed. Landslides and rockfalls damaged or destroyed several mountain roads and railways and buried buildings in the Beichuan-Wenchuan area, cutting off access to the region for several days.[8]

Responses

The authorities responded to the news about the earthquake rapidly. Just 90 minutes after the main shock, Premier Wen Jiabao flew to the disaster zone to oversee the rescue work.[9] The government started the flow of supplies to the area on the day of the earthquake and mobilized approximately 130,000 – 140,000 People’s Liberation Army soldiers and paramilitary police to the affected region. Government ministries and departments, mass organizations like the Communist Youth League (CYL) and so-called GONGOs such as the Chinese Red Cross sent supplies and search-and-rescue teams, and mobilized volunteers and funds through their national networks. A week after the earthquake, the Sichuan provincial CYL estimated that it had about 200,000 volunteers in the earthquake areas.[10] Both the CYL and Red Cross were quickly able to secure permission to work in the disaster area and raise money for the relief effort, but they lacked staff to make use of their resources efficiently.[11]

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, media was allowed to report from the affected area in an exceptionally open manner, and for a while, even highly critical reports were published.[12] This short period of relative openness was the first time in the People’s Republic the Chinese media public was intensely exposed to the scenes of large-scale disaster and suffering, an experience that generated wide-spread sympathy for the victims and survivors. Individuals, companies and civil society organizations volunteered to help the affected population by donating money, blood and goods. In many cases, volunteers also travelled to the disaster area to assist in rescue and relief work and the local taxi drivers provided an important transportation channel.[13] Even though Chinese authorities usually view NGOs with suspicion, in the immediate aftermath of the Wenchuan earthquake, they temporarily loosened legal restrictions. Non-governmental organizations and informal groups nevertheless experienced difficulties with the authorities.[14] Despite the challenges, volunteers and grassroots organizations managed to play an important role in the relief work, even though their inexperience with such tasks occasionally drew criticism and the window of opportunity for their participation proved to be rather short-lived. The sheer scale of the demand for help overwhelmed the authorities’ capacity to deal with the situation, but on top of that the local state apparatus in most devastated places was seriously damaged.[15]

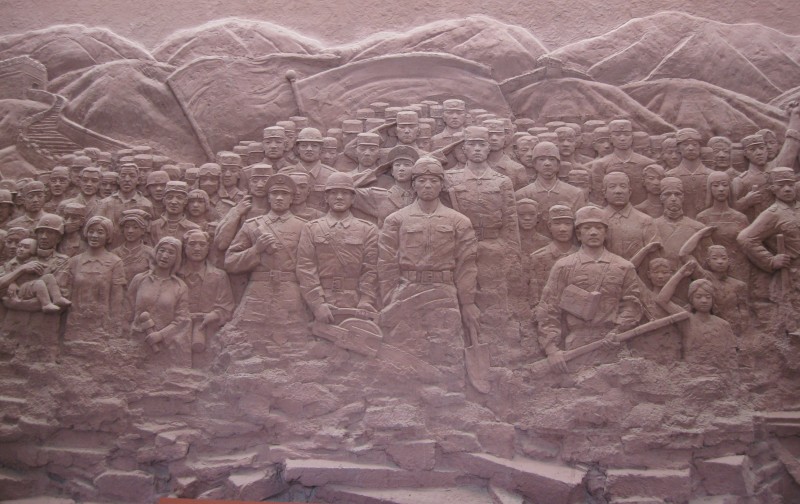

Mural of the Wenchuan Earthquake at the Jianchuan Museum Cluster, located outside the Sichuan provincial capital, Chengdu

Source: Jianchuan museum mural, photo taken by author

The response to the Wenchuan earthquake was rapid, particularly when compared with the 1976 Tangshan earthquake or the blizzard that hit China earlier in 2008. For example, Richard Suttmeier concludes that compared to the aforementioned disasters, response times were good, interagency coordination between central ministries and between central ministries and local authorities was rather effective, information management was improved, and civil society actors had opportunities to participate in the response.[16] However, problems were not uncommon. There were issues in the chain of command between the civilian and military leaders; there was a shortage of necessary equipment, such as tents and tarpaulins; preparedness level was inadequate; and corruption hampered the reconstruction.[17] Moreover, several remote and scattered villages could not be reached for several days because of blocked roads and inadequate numbers of professional rescue teams.[18]

Reconstruction

In the Post-Wenchuan Earthquake Recovery and Reconstruction Master Plan the total cost was estimated to be one trillion yuan.[19] The provincial governments in quake-stricken areas were responsible for the enforcement of the post-earthquake restoration and reconstruction. The local (township and village/neighbourhood) government, on the other hand, were tasked with distributing compensations and building dwellings. The governments at and above the county level were required to raise funds for the post-earthquake restoration and reconstruction by such means as government investment, one-to-one assistance, social fund-raising and market operation.[20]

News reel clip reporting the earthquake on CCTV in May 2008.

Source: CCTV, ‘CCTV report of Sichuan earthquake,’ newsreel, May 12, 2008

The official target for completing the housing reconstruction was set to be September 2010, but according to the survey conducted by CASTED (Chinese Academy of Science and Technology for Development) and Norwegian Fafo Institute of Applied International Studies, 0.6 percent of the surveyed households still lived in tents or other temporary housing in the summer of 2011.[21] Households who needed to repair or rebuild their homes were offered cash subsidies, low-cost loans and tax exemptions, but family savings were still the most important source of funding especially for those who needed to buy or rebuild. Among the households that had to repair their house or obtain a new one, 80 percent received government subsidies for doing so. Government subsidies covered approximately 40 percent of the reparation costs in both urban and rural areas. However, for households that had to rebuild or buy a new house government assistance accounted for only 26 percent for rural areas and 12 percent for urban households.[22] Most rural households rebuilt their houses either by themselves or with the county[23] and local level government guidance, whereas urban households were more likely to receive a new house, presumably by a special-built replacement or new purchase.[24]

Even though the Sichuan provincial government required that all affected houses should be evaluated and should undertake earthquake-proof measures during reparation and rebuilding, these policies did not materialize very well. The Fafo-CASTED survey found that in 2011, when the reconstruction was completed, only 43 percent of households (N=3754 households) in the survey area lived in a house reinforced with earthquake-proof measures. The situation was somewhat better with new-built or bought houses, 75 percent of which (N=1500 households) complied with the anti-seismic building standards.[25]

Disaster politics

During and after the Wenchuan disaster, state propaganda emphasized the efficient leadership of the Communist Party and the heroic rescue efforts of the People’s Liberation Army. Also national unity and selfless heroism of ordinary citizens were important themes of the official discourse. However, these narratives that emphasised the positive aspects of rescue and relief were challenged by the news that thousands of students had died in shoddy school-buildings. The exact number of student victims is not known and the figures vary from the official death toll of 5,335 to the estimate released by Reuters news agency soon after the disaster that put the number of deaths to as high as 9,000. This estimate was based on figures released in the reports of Xinhua and local media.[26]

The Old Beichuan city, which now serves as an outdoor museum to the disaster, as seen in July 2014

Source: Photo taken by the author, 2014

In addition to independent investigations into various aspects of the disaster, including school collapses and student deaths by parents and environmentalist Tan Zuoren and artist Ai Weiwei, among others, Fan Xiao, the chief engineer of the Sichuan Geology and Mineral Bureau, published an article that claimed that the large Zipingpu reservoir had possibly increased the seismic instability in the area and triggered the quake, but the theory is hypothetical at best. It connects, however, to sensitive questions of government responsibility and the battles over hydropower projects in Sichuan, which is why the topic was censored in China.[27]

Marjaana Mäenpää is a doctoral candidate at the Department of Philosophy, Contemporary History and Political Science at the University of Turku, Finland.

NOTES

[1] Xu, Bin (2012): “Grandpa Wen: Scene and political performance”. Sociological Theory, 30(2), p.124.

[2] Qian Gang (2009a): “Learning our hard lessons from Sichuan’s March 2008 earthquake quiz competitions”. China Media Project blog. May 12. <http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/12/1608/>. [Accessed January 27, 2016.] For example, Beichuan suffered from M 6.2 earthquake in 1958 and in 1976 quakes took place at Songbo and Pingwu.

[3] Zhang, Peizhen: “十一届全国人大常委会专题讲座第四讲中国地震灾害与防震减灾”. Published on the website of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. <http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/xinwen/2008-06/30/content_1435752.htm>. [Accessed February 1, 2016.]

[4] Sichuan zhengbao (2005): ”四川省人民政府关于进一步加强防震减灾工作的通知”. 川府发[2005]6号. January 31.<http://www.sc.gov.cn/sczb/lmfl/szfwj/200706/t20070608_185659.shtml>. [Accessed February 1, 2016.]

[5] Qian 2009a.

[6] China Media Project: “A news story on school collapses tantalizes, then disappears”. May 26, 2009. http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/26/1641/. [Accessed March 2, 2016.] The news story on the research originally appeared in China Economic Weekly and was reposted by China Media Project.

[7] Xinhua: ”权威发布:四川汶川地震抗震救灾进展情况”. August 25, 2008. <http://news.xinhuanet.com/newscenter/2008-08/25/content_9707753.htm>. [Accessed January 28, 2016.]

[8] US Geological Survey: “M7.9 – eastern Sichuan, China”. <http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/usp000g650#general_summary>. [Accessed January 18, 2016.]

[9] China.com.cn: ”5.12四川汶川7.8级地震日志:5月12日”. May 17, 2008. <http://www.china.com.cn/news/txt/2008-05/17/content_15287221.htm>. [Accessed January 29, 2016.]

[10] GONGO = Government organized non-governmental organization. Shieh, Shawn & Deng Guosheng (2011): “An emerging civil society: The impact of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake on grassroots associations in China”. Research report. The China Journal, 65, p. 185.

[11] Xu, Bin (2014): “Consensus crisis and civil society: The Sichuan earthquake response and state-society relations”. The China Journal, 71, p. 95.

[12] The Central Party Propaganda Department forbade sending journalists to the quake zone but this verbal ban was made obsolete by the Central Politburo, who instructed the Xinhua News Agency and China Central Television to report on the disaster in “timely, accurate, open and transparent” manner (Xu 2012, p. 120). Nevertheless, the Central Propaganda Department prohibited the detailed reporting on school collapses on May 15, but in practice the ban was enforced only in June. Before that, several critical articles were published and even though most of them appeared online, they there published by established commercial media outlets such as Southern Metropolis Daily and Southern Weekend and even by Party mouthpieces, such as People’s Daily and Xinhua. (Bandurski, David (2008):, ‘中国媒体大地震’ (The great earthquake of Chinese Media). Wall Street Journal China Online, May 29. <http://chinese.wsj.com/gb/20080529/opn091318.asp?source=email>. [Accessed 15 May 2014]; Qian, Gang, (2009b): “Looking back on Chinese media reporting of school collapses”. China Media Project blog, May 7. http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/07/1599/. [Accessed 15 May 2014.])

[13] Xu, Bin (2009): “Durkheim in Sichuan: the earthquake, national solidarity and the politics of small things”. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72(1), pp. 5 – 8; Paik, Wooyeal (2011): “Authoritarianism and humanitarian aid: regime stability and external relief in China and Myanmar”. The Pacific Review, 24(4), pp. 439 – 462; Xu 2012, pp. 120 – 121.

[14] Roney, Britton (2011): ”Earthquakes and civil society: A comparative study of the response of China’s nongovernment organizations to the Wenchuan earthquake”. China Information 25(1), p. 86; Xu 2014, pp. 98 – 99.

[15] Xu 2014, p. 94.

[16] Suttmeier, Richard P. (2011), “China’s management of environmental crises”. In Jae Ho Chung (ed.), China’s Crisis Management. Routledge, p. 116.

[17] See for example. Suttmeier 2011, pp. 116–117; Yang, Jun et al (2014): “Comparison of two large earthquakes in China: the 2008 Sichuan Wenchuan Earthquake and the 2013 Sichuan Lushan Earthquake”. Natural Hazards, 73, p. 1130.

[18] Suttmeier 2011, 117; Xu 2014, p. 94.

[19] Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China: ”汶川地震灾后恢复重建总体规划”. 国发〔2008〕31号. September 23, 2008. <http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2008-09/23/content_1103686.htm>. [Accessed February 1, 2016.]

[20] The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: “Regulations on Post-Wenchuan-Earthquake Restoration and Reconstruction”. Order of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Order No. 526. June 8, 2008. http://www.sc.gov.cn/10462/10758/10759/10764/2012/7/26/10219700.shtml. [Accessed March 3, 2016.]; Dalen, Kristin, Hedda Flatø, Liu Jing and Zhang Huafeng (2012): Recovering from the Wenchuan Earthquake: Living Conditions and Development in the Disaster Areas 2008-2011, Fafo-report, 39 p. 174.

[21] Dalen et al (2012), p. 43. The first round of survey took place soon after the earthquake in 2008 (n=3652 households), the second one year later (n=4015 households), and the last three years later in the summer 2011 (n=3841 households).The final report (Dalen et al) was published in 2012. The stated purpose of the first survey was to provide Chinese authorities information on the circumstances and needs of the people living in the disaster area, while the second and third survey aimed at assessing the implementation of reconstruction plan and its impact on the affected households. Survey design, sampling methods and fieldwork are explained in the final report, Dalen et al (2012), pp. 15-16.

[22] Dalen et al (2012), pp. 36-37, 43-44.

[23] The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: “Regulations on Post-Wenchuan-Earthquake Restoration and Reconstruction”.

[24] Dalen et al, p.43.

[25] Dalen et al., p. 49.

[26] The Guardian: “China releases earthquake death toll of children”. May 7, 2009. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/may/07/china-earthquake-anniversary-death-toll>. [Accessed January 15, 2016.] Chen Min, ‘[重建之思] 真相比荣誉更重要——林强访谈录’ ([Thinking about reconstruction] Truth is more important than glory – the record of the interview with Lin Qiang). Southern Weekend, 30 May 2008. <http://www.infzm.com/content/12753>. [Accessed May 14, 2014.] Sichuan province’s own investigation report stated that there were five reasons for the collapse of schools: the earthquake surpassed the forecasted strength; the quake struck at a time when classes were still on; third, the classrooms and corridors, where the most students were, were weakly connected; the buildings were old-fashioned and backward; and the design of anti-seismic elements in the construction had some innate flaws. However, the sheer force of the quake was considered to be the main reason for destruction.

[27] Roney 2011, pp. 89-90.

SOURCES

Bandurski, David (2008):‘中国媒体大地震’ (The great earthquake of Chinese Media). Wall Street Journal China Online, May 29. <http://chinese.wsj.com/gb/20080529/opn091318.asp?source=email>. [Accessed 15 May 2014]

Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China: ”汶川地震灾后恢复重建总体规划”. 国发〔2008〕31号. September 23, 2008. <http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2008-09/23/content_1103686.htm>. [Accessed February 1, 2016.]

Chen Min, ‘[重建之思] 真相比荣誉更重要——林强访谈录’ ([Thinking about reconstruction] Truth is more important than glory – the record of the interview with Lin Qiang). Southern Weekend, 30 May 2008. <http://www.infzm.com/content/12753>. [Accessed May 14, 2014.]

China.com.cn: ”5.12四川汶川7.8级地震日志:5月12日”. May 17, 2008. <http://www.china.com.cn/news/txt/2008-05/17/content_15287221.htm>. (Last visited January 29,

2016.)

China Media Project: “A news story on school collapses tantalizes, then disappears”. May 26, 2009. http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/26/1641/. [Accessed March 2, 2016.]

Dalen, Kristin, Hedda Flatø, Liu Jing and Zhang Huafeng (2012): Recovering from the Wenchuan Earthquake: Living Conditions and Development in the Disaster Areas 2008-2011, Fafo-report, 39.

Paik, Wooyeal (2011): “Authoritarianism and humanitarian aid: regime stability and external relief in China and Myanmar”. The Pacific Review, 24(4), pp. 439–462.

Qian Gang (2009a): “Learning our hard lessons from Sichuan’s March 2008 earthquake quiz competitions”. China Media Project blog. May 12. <http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/12/1608/>.

Qian, Gang, (2009b): “Looking back on Chinese media reporting of school collapses”. China Media Project blog, May 7. http://cmp.hku.hk/2009/05/07/1599/. [Accessed 15 May 2014.]

Roney, Britton (2011): ”Earthquakes and civil society: A comparative study of the response of China’s nongovernment organizations to the Wenchuan earthquake”. China Information 25(1), pp. 83–104.

Shieh, Shawn & Deng Guosheng (2011): “An emerging civil society: The impact of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake on grassroots associations in China”. Research report. The China Journal, 65,

Sichuan zhengbao (2005): ”四川省人民政府关于进一步加强防震减灾工作的通知”. 川府发[2005]6号. January 31. <http://www.sc.gov.cn/sczb/lmfl/szfwj/200706/t20070608_185659.shtml>. (Last accessed February 1, 2016.)

Suttmeier, Richard P. (2011), “China’s management of environmental crises”. In Jae Ho Chung (ed.), China’s Crisis Management. Routledge, pp. 108–129.

The Guardian: “China releases earthquake death toll of children”. May 7, 2009. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/may/07/china-earthquake-anniversary-death-toll>. [Accessed January 15, 2016.]

The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: “Regulations on Post-Wenchuan-Earthquake Restoration and Reconstruction”. Order of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Order No. 526. June 8, 2008. http://www.sc.gov.cn/10462/10758/10759/10764/2012/7/26/10219700.shtml. [Accessed March 3, 2016.]

US Geological Survey: “M7.9 – eastern Sichuan, China”. <http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/usp000g650#general_summary> (Last visited January 18, 2016)

Xinhua: ”权威发布:四川汶川地震抗震救灾进展情况”. August 25, 2008. <http://news.xinhuanet.com/newscenter/2008-08/25/content_9707753.htm>. (Last visited January 28, 2016.)

Xu, Bin (2014): “Consensus crisis and civil society: The Sichuan earthquake response and state-society relations”. The China Journal, 71, pp. 91–108.

Xu, Bin (2012): “Grandpa Wen: Scene and political performance”. Sociological Theory, 30(2), 2012, pp. 114–129.

Xu, Bin (2009): “Durkheim in Sichuan: the earthquake, national solidarity and the politics of small things”. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72(1), pp. 5–8.

Yang, Jun, Chen Jinhong, Liu Huiliang & Zheng Jingchen (2014): “Comparison of two large earthquakes in China: the 2008 Sichuan Wenchuan Earthquake and the 2013 Sichuan Lushan Earthquake”. Natural Hazards, 73, pp. 1127–1136.

Yin, Liangen and Wang Haiyan (2010): “People-centred myth: Representation of the Wenchuan earthquake in China Daily”. Discourse & Communication, 4(4), pp. 383 – 398.

Zhang, Peizhen: “十一届全国人大常委会专题讲座第四讲中国地震灾害与防震减灾”. Published on the website of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. <http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/xinwen/2008-06/30/content_1435752.htm>. (Last accessed February 1, 2016.)