1876至1879年間,中國皇朝漫長的飢荒災難史上最致命的乾旱飢荒襲擊了山東,直隸,山西,河南,陝西這五個北部省份。黃河流域盆地的乾旱從1876年開始,在1877年時,因為全面性的缺雨而急遽惡化。 直到1879年,狀況開始穩定,受影響地區的總人口為1.08億人, 據估計其中的950萬-1300萬人死於飢餓以及與饑荒相關的疾病。[1]

因果關係

在1870年代末期,重創華北地區的嚴重旱災是催化劑,而不是造成大飢荒的根本原因。像清朝這種廣大且高度商業化的經濟體,區域性的嚴重匱乏不一定會造成重大的饑荒。十八世紀期間,清朝政府存放和分配糧食的能力與投入達到巔峰,曾多次有效地預防嚴重乾旱所導致的大規模饑餓。[2] 相比之下,十九世紀中葉的叛亂、財政危機、缺乏強大的領導能力和外國帝國主義的壓力下,使得十九世紀末期的清朝政府勢力已大幅削弱。因此,清朝再也無法動用必要的介入來預防乾旱造成的飢荒。十九世紀中期的叛亂從1850年代開始,使國家資源和各省資源的耗費達到危險的程度,因此國家無法準備就緒處理嚴重的乾旱。太平之亂(1851-1864),捻亂(1853-1868)和穆斯林革命(1855-1873)對財政影響巨大。據統計,軍費佔政府總支出的近四分之三。太平戰爭摧毀了一些中國最富有的長江流域的省分,來自十三個省份的土地稅和鹽巴壟斷的收益所產生的國家資金因此中斷。同時,捻亂的叛亂者中斷了政府在北部四省的行政管理,而穆斯林革命使西南和西北地區人口減少. [3] 為了壓制這些十九世紀中葉的叛亂,清朝耗費了相當大的努力,造成了糧倉管理系統的大浩劫。尤其是在乾旱多發的北方省份,清朝官員依靠國家和社區糧倉來維持較低的糧食價格,並在生計危機期間提供緊急救援。糧倉系統的衰落始於1790年代,並在十九世紀中葉的叛亂之後達到危機。這樣的衰頹意味著,在1870年代華北地區乾旱蔓延時,清朝政府對抗嚴重糧食危機的第一道防線,大多被地方精英所執行的臨時系統所取代,這些人缺乏維持大型糧倉和執行重要的區域間穀物轉移的國家能力。[4]

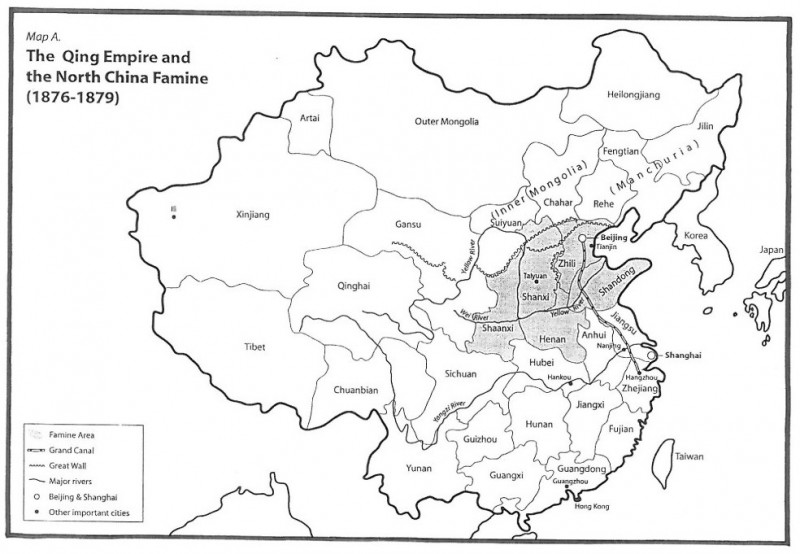

大清帝國與華北饑荒

Source: Graphic Services, Indiana University

財政問題也是造成清末國家無力及時解除乾旱的原因。十八世紀,由於國家財政充裕,中央政府官員能夠維持有效的糧倉制度,糧食通常維持在二千萬噸或以上。 直至1870年代,旱災襲擊華北,清朝的國庫遭受重大的情勢逆轉。十八世紀末期,財政儲備開始衰退,當時國家必須花費十萬兩白銀,來壓制1796-1804年的白蓮花叛亂。十九世紀初期,徵稅變得更加困難,皇朝官員自清初的2000名成員增加到30,000名,一年要花費幾百萬兩白銀的俸祿。[5] 隨著世紀交替,生態破壞造成的水災日益嚴重,維護黃河堤壩的成本大幅增加。[6] 軍事對立後賠償獲勝的西方強國,以及資助海岸防禦工程以改善能力驅逐海上侵略者,都帶來更多的財政壓力。西方以及日本的帝國主義者帶來的威脅,也迫使清朝統治者及高層官員針對如何妥善利用減少的資源,做出困難的抉擇。1856-60年的鴉片戰爭,清朝戰敗英國和法國的恥辱,加深西方對於中國的威脅。而1874年,日本在台灣的「懲罰性考察」,則顯示出日本有意挑戰清朝政府在東亞的優勢。大清帝國的西北邊境也遭受攻擊,當時富裕的伊利谷,也就是現代的新疆,在十八世紀中葉時清朝皇帝一直積極努力征服,在1871年被俄羅斯入侵和占領。為了收復今日的新疆,政府採取昂貴的軍事行動,與飢荒最嚴重的年頭正好吻合,使得國家對於華北災民的救災工作更為艱辛。[7] 缺乏強有力的領導,是阻礙清末政府能快速並有效應對乾旱的另一個因素。在1876-1879年大旱災時期,皇室特別積弱不振,因為1895年,乾旱的前一年,發生了光緒皇帝繼承王位的合法問題。1870年代後期,失去強勢的皇室領導的清朝政府,比過去更難以實施大規模支出的飢荒政策。[8] 總而言之,內亂,外侵,財政問題,糧食系統的瓦解,以及權力高層的薄弱與分化,使得清朝政府無法處理旱災規模等同於1876年至1879年襲擊華北的大旱災。[9]

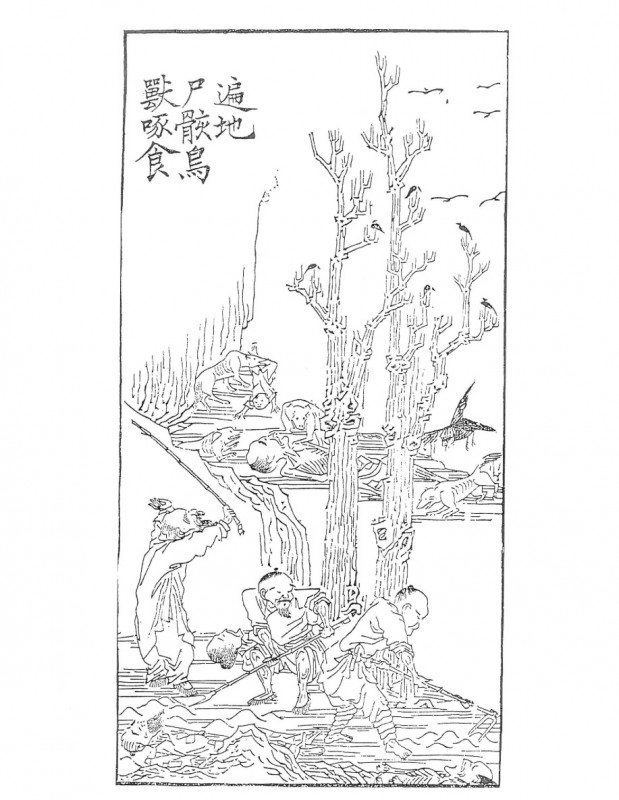

木版印刷:尚未被埋葬的屍體被鳥類與野獸吞噬

Source: “Si sheng gao zai tu qi,” shou juan (Pictures reporting the disaster in the four provinces, opening volume), in Qi Yu Jin Zhi zhenjuan zhengxin lu (Statement of accounts for relief contributions for Shandong, Henan, Shanxi, and Zhili) (n.p., 1881), 14a. Courtesy of the Shanghai Library.

對策

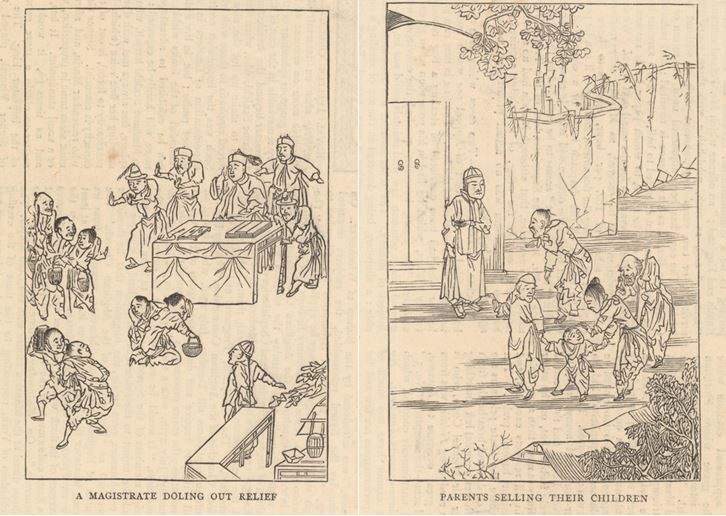

中國對1876 – 1979年華北飢荒的對策,反映出中國千年以來對於飢荒成因的傳統思維,而且在國共時代,這些新議題預料將會變得越來越重要。如同康雍乾盛世的祖先,1870年代的清朝統治者和官員呈現出仁慈的人民父母的模樣,將飢餓的人視為需要國家幫助的受苦孩童。他們進行一系列儀式,藉由展現誠意以及對人民的痛苦的深切關懷,祈求感動上蒼,使天下雨。[10] 國家還依靠歷史悠久的策略,例如,在災區,以低於市場的價格出售國家糧食,以穩定糧食價格,減少或者取消課稅,調查受影響地區,根據房屋的受災程度做分類,並與當地精英合作,開設廚房與收容所。[11] 身為中國海關官員和歷史學家的H.B.莫爾斯計算出1876年至1878年間,清朝政府給予受旱災的山西,河南,陝西,直隸地區1800多萬兩的減免稅,超過「國庫一年總收入的五分之一。」中央政府還撥款500多萬兩,直接援助救荒,並命令飢荒地區以外的省份讓乾旱省份借貸額外的救濟金。[12] 然而,與康雍乾盛世不同的是,1870年代的政府不再有資源和意願,將大量糧食運送給受災群眾。例如,在飢荒最為嚴重的山西,政府救災辦事處共發放一千零七十萬兩的救災金,但救災糧食只有一百萬石。[13]

木板印刷:地方官發放救濟物資,及父母正販賣他們的孩子

Source: The Graphic (London), July 6, 1878. From the collection of Pierre Fuller.

災難的嚴重性和範圍不僅激起清朝朝廷以及負責紓困北方省份的官員採取行動,西方傳教士以及生活在富裕江南地區(揚子江南部)的中國慈善家也跟著行動。上海出版的中英文報紙大幅報導這個災難。在1877年春天,上海大型外國社會團體的重要成員回應傳教士的援助呼籲,遊說外國人捐助救濟金。[14] 1878年1月,中國飢荒救濟基金委員會在上海成立,擴大在海外的籌款活動,並監督三十名負責將委員會募到的現金發放給山西,山東,直隸的飢荒災民的外國救災分配員(主要是英美新教傳教士)。委員會共收到並分發204,560兩的救濟金。至少有四十名與上海委員會沒有官方關係的天主教徒,也參與救濟。[15] 晚清時期,清朝無力為北方乾旱省份提供充足的救濟; 加上中國新起的西式報紙對飢荒的批判報導,最關鍵的是上海的《申報》,也刺激江南地區的中國學者,商人和官員,組成廣大的飢荒救災網絡。到了1878年的夏天,籌畫救災的仕紳與商人在上海,杭州,蘇州和揚州,設立特別救濟辦事處(協賑公所)。在接下來的三年,這些網絡共同合作,募得一百多萬兩的救災費用。他們與天津的官方救災辦事處合作,但保持獨立分開。[16]

結果

對一個已經陷入內部動亂,外來侵略和財政困境的帝國而言,華北的饑荒顯得是個嚴重危機。雖然清朝統治者與官員未放棄「國家有養育人民的責任」的言論,但實際上,在1870年代後期,官員們對於如何將匱乏的資源分配給饑荒救濟和軍費支出有很大的歧見。一群強勢官員和滿族王子,想將中國有限的資源用於自強項目,尤其是海防。另一群有影響力的官員們認為,西北的邊防,特別是收復新疆的運動,比海上防衛更為緊迫。最後,一群被稱為清流(Pure Stream)的低階官員們認為,解除饑荒應該是政府的首要任務。清廷官員間的意見分歧,阻礙政府快速有效地應對饑荒的能力。一個堅強並且自信的皇帝,當時或許可能阻止內鬨。不幸的是,在1870年代後期,沒有任何一個人或團體有權力和信心去制定明確的政策。相反地,衰弱的清廷不斷在不同的想法中搖擺,例如是要跟隨清流的觀念:「養育人民應該是仁慈之國的首要任務」,或是跟隨自強派的想法,認為保衛領土抵擋外國的入侵更加迫切。自強派與清流支持者之間的辯論,意味著兩方對於重大災難的詮釋無法達成共識。到了1870年代,了解饑荒意義以及飢荒所需的何種對策,如此的整體背景慢慢地從統治者的主要議題為避免失去天命,轉變為強調保衛國家抵擋貪婪強取且日益強大的外國勢力。[17]

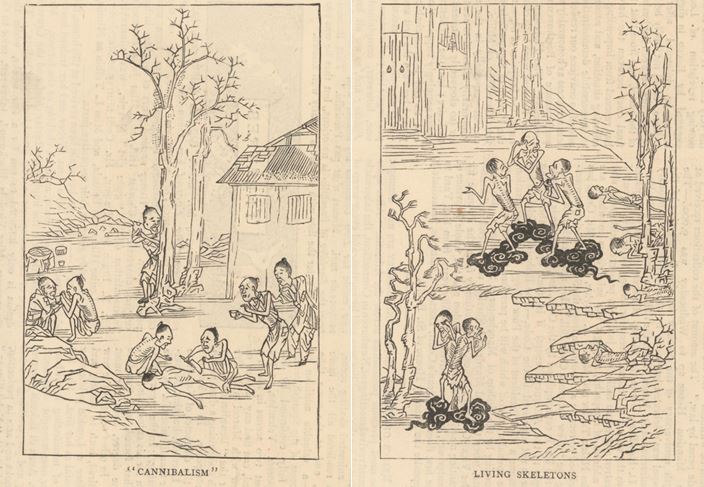

木板印刷:人類互食,與瘦骨如柴的人們

Source: The Graphic (London), July 6, 1878. From the collection of Pierre Fuller.

正如瑪麗蘭金、朱胡、安德烈·揚庫克,以及凱瑟琳·埃德頓塔普利合著的作品所顯示,饑荒對於在富裕的江南地區具有影響力的精英,也產生重大的影響。在那裏,這場災難使得中國慈善家們越過他們的地域,專注於遙遠的華北地區挨餓的陌生人,而不是在自己土生土長所在的窮人。他們與外國人主辦的救濟活動進行競爭,在國家無法養育人民時擔負起政府官員的職責。[18] 中國政府救災工作的延遲和貧乏讓江南精英們強烈失望,也引起對清朝官僚政府的批評和巨大的改革呼聲。面對外國對清政府救災工作不斷的砲火攻擊,以及因為外國傳教士趕到北方省份發放救援物資而造成的質疑,江南商界和文學界精英們開始認為這次飢荒是國家恥辱。尤其是在上海,這個饑荒是19世紀主要的危機之一,迫使通商港的精英活躍分子,開始約瑟夫·列文森所謂的從「文化主義」轉向「民族主義」的過程。現代的民族主義在1860年代開始進入中國,不同於早期的中國身份形態,現代的民族主義既強調國家之間的競爭,而且拒絕以往構成中國身份的方式。」[19] 國外的批評、海外救援工作的新資訊,以及傳教士在中國的救濟活動,迫使上海受過教育的中國人不安地思索,中國可能不是「全天下」,而只是「眾多國家之一」,因此中國的饑荒救災方式,並不是「救災方法」,而只是處理災難的眾多方式之一。 [20]

史地概觀

僅管在1870年代,饑荒受到國內和國際的廣泛關注,但是二十世紀絕大部分,華北饑荒被中外學者所遺忘。一直到1958 – 62年毛澤東時代的大躍進飢荒,造成大約三千萬人死亡,人民的記憶才被刻意拉回到1870年代末期的恐懼,藉此淡化中華人民共和國在養育人民方面全然的失敗。1960年代初期出版了有關「清末饑荒」的討論,直接了當地將華北饑荒歸咎於貪婪的官員,並認為只有在自相殘殺的舊「封建社會」中,貪腐的領導人,強取豪奪的地方精英,以及有缺陷的社會制度,使得天災導致大規模的飢餓,甚至是家庭內的同類互食。[21]

木版印刷: 飢餓死亡的母親和孩子,和因為饑餓而自殺的人。

Source: The Graphic (London), July 6, 1878. From the collection of Pierre Fuller.

1980年代,進行國家級研究的中國史學家們對於1876 – 1979年的饑荒產生興趣,以它身為為害清末中國的重大天災之一來做研究。華北飢荒原本被視為是體現「舊封建社會」的貪腐與無情的實例,但是文化大革命後,有關華北饑荒的學術文獻已經轉移觀點。新的焦點是檢驗1876 – 1879年的饑荒以及其他的清末災難是否是中國在十九世紀時落後西方的可能關鍵,是否是晚清「現代化」的努力成為空談的原因。例如,歷史學家夏明芳主張,1861-1895年的自強運動旨在促進工業化以強化中國,卻因為一連串代價昂貴的破壞性旱災和水災而嚴重受阻。根據夏明芳的論點,這些災難耗盡清朝國庫,轉移了官員們對現代化建設的注意力,阻礙了原始資本的累積,阻礙了十九世紀末期中國的商品和勞動市場的發展。[22]

有關這場饑荒的影響,社會學家麥克·戴維斯(Mike Davis)已將討論推向全球性。他認為在十九世紀,和旱災有關的毀滅性飢荒襲擊中國、印度、巴西、非洲南部和埃及,既是徵兆也是原因,說明了十八世紀次大陸強國體系的前核心區域轉變為以倫敦為中心的世界經濟中的飢餓圈。[23] 戴維斯指責帝國主義對殖民地和半殖民地實行自由市場經濟,造成驚人的饑荒死亡人數。戴維斯認為,就中國的情況而言,國家能力與普及福利急遽衰退,尤其隨著清朝政府被英國及其他強國強迫「開放」現代化,飢荒救災也跟著同步衰退。戴維斯認為,「我們今天所說的『第三世界』是收入和財富不平等的產物,在非歐洲農民最初融入世界經濟時,產生十九世紀最後的十五年決定性改變。」[24] 最後,受文化歷史的影響,安德烈·揚庫克和凱瑟琳·埃德頓塔普利的近期著作,考察中國對1876 – 1979年,華北饑荒的回應與解讀。例如,在揚庫克的其中一篇文章,他表明,西方傳教士與江南慈善家在飢荒期間,進行籌款活動的競爭,是一種「精神層面上的對抗」,與十九世紀末延續至二十世紀初中國的「佛教復興」相關。 [25] 埃德頓塔普(Edgerton-Tarpley)關於飢荒的專著《鐵眼淚》(2008),分析災難產生的不同文化與政治反應。書中的一個章節研究鬧飢荒的山西省村民、負責救濟工作的省政府和中央政府官員、 通商港口的慈善家、以及英美傳教士與記者等人如何解釋饑荒的因果關係,如何定義大規模饑餓下的道德與不道德的反應。最後一章探討中國觀察家挑選重要影像與故事來顯示饑荒的可怕。

來源類型

關於1876-79年的華北飢荒,有許多主要的參考資料。有許多容易取得的地方資料,例如地方志或是文史資料的出版品,特別是山西省的相關資料。上海及蘇州的中國慈善家所設計的木板印刷插畫以及附帶的哀悼(詳見:參考書目中的《齊豫晉直賑捐賑興錄》),可以在上海圖書館找到,而上海申報則提供了詳細的災難報導。在紀念饑荒的相關出版品、總理衙門所搜集的法令(詳見:《籌辦各省荒賑案》,以及《光緒朝東華錄》中皆可找到重要的省級官員與中央官員的觀點。有用的飢荒英文主要文獻包括上海的《北華捷報》、英國國會文件中的一份冗長的報導《天朝》,以及傳教士的出版品,如《億萬華民》以及李提摩太的《在中國的四十五年》。在二手文獻方面,中國出版的饑荒相關研究書籍,包含何漢威的《光緒初年》 (1876-79) 《華北的大旱災》(1980), 朱滸的 《地方性流動及其超越:晚清義賑與近代中國的新陳代謝》 (2006), 以及郝平的《丁戊奇荒:光緒初年山西災荒與救濟研究》(2014)。 而英文版的研究書籍則包括保羅·理查德·玻爾的《中國的饑荒與傳教士:救濟行政官與國家改革倡導者李提摩太,1876-1884 (1972)》,埃德頓塔普(Edgerton-Tarpley)的《鐵眼淚:中國十九世紀飢荒的文化反應》(2008)。 夏明芳,李文海,安德烈·揚庫,瑪麗·蘭金,李莉安·李和邁克·戴維斯都出版了關於這場災難的重要文章或書籍章節(見參考書目)。

度量

死亡率:難以估計華北饑荒期間的死亡率。1879年,中國饑荒救難基金委員會提出報告,估計山西死亡人數550萬人,直隸250萬人,河南省100萬人,山東50萬人,總計共有950萬人因為飢餓以及與饑荒有關的疾病而死亡,如斑疹、傷寒與痢疾。李立蓮指出,因為救災行動確實抵達直隸省受創最嚴重的南部地區,因此,報告中直隸的死亡人數為250萬可能高估了。另一方面,山西的死亡人數可能更高(見下文),報告中並沒有估計也受旱災影響的陝西省的死亡人數。現代歷史學家一般估計死亡人數為950-1300萬人之間。

在推估饑荒中心的山西省因飢荒而損失的人口時出現極大的差異。外援工作人員估計,山西地區在飢荒前有1500萬人,而約有550萬人死於饑荒和隨之而來的瘟疫。對比之下,山西省省長曾國權在災情將結束時寫道,山西有近一半的人民,在災難一開始時就死了,而且因為傳染病的緣故持續有人死亡。飢荒過後不久,在曾國權的命令下,編纂了《山西省地名詞典》並在1892年出版,書中提到,根據人口登記,饑荒期間的死亡人數不下1000萬。劉Rentuan近來利用地名錄來研究飢荒對於1877年到1953年間的山西人口的影響。他發現山西省飢荒前的人口以及飢荒死亡人數都高於國外的估計值,但是低於曾國權所估計的數字。劉先生指出,1876年至1880年間,山西人口從1720萬人下降到960萬人,人口減少44.2%。不幸的是,不可能從地名錄來確定失踪的數百萬人當中有多少是在飢荒時期死亡的,有多少人是遷徙到其他地區。

地理範圍:乾旱和饑荒影響山東,直隸,山西,河南,陝西等五個北部省份,佔地面積約30萬平方英里。

受影響人口:鬧旱災的華北五省約1.08億人口。

時間:三年 – 1876年夏天至1879年夏天。最嚴重的時期是1877年至1878年。乾旱山東,直隸開始,接著蔓延到山西,河南,陝西。

凱瑟琳·埃德頓塔普是聖地亞哥州立大學,晚期帝國與現代中國歷史的副教授。

翻譯: 邱奕齊

注釋

[1] R.J. Forrest, “China Famine Relief Fund” (Shanghai, 1879), 1, 9; Susan Cotts Watkins and Jane Menken, “Famines in Historical Perspective,” Population and Development Review 11 (1985): 650.

[2] Pierre-Etienne Will, Bureaucracy and Famine in Eighteenth-Century China, trans. Elborg Forster (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990); Lillian M. Li, Fighting Famine in North China: State, Market, and Environmental Decline, 1690s-1990s (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), chapter 8.

[3] Pao Chao Hsieh, The Government of China, 1644-1911, (Baltimore: The Johns Hpkins Press, 1925), 205-206, 214; Philip A. Kuhn, “The Taiping Rebellion,” in The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 10, 264-316.

[4] Pierre-Etienne Will and R. Bin Wong, Nourish the People: The State Civilian Granary System in China, 1650-1850 (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, 1991); Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World (London: Verso, 2001).

[5] Will, Bureaucracy and Famine, 290-92.

[6] Li, Fighting Famine, chapters 2 and 9; Will, Bureaucracy and Famine, 292-93.

[7] Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron: Cultural Responses to Famine in Nineteenth-Century China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 28-39, 92-102. The Xinjiang campaign cost 52.3 million taels between 1875 and 1881. Xinjiang became a full-fledged Chinese province only in 1884.

[8] Richard Horowitz, “Central Power and State-Making: The Zongli Yamen and Self-Strengthening in China, 1860-1880,” (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1998), 105-106.

[9] Mike Davis demonstrates convincingly that the cause of the severe droughts that impacted places as diverse as northern China, India, southern Africa, and northeastern Brazil in the late 1870s was a particularly powerful “El Nino event,” or a rapid warming of the eastern tropical Pacific that led to the prolonged and virtually complete failure of the monsoons that normally provide rainfall for the affected areas. The grand “El Nino event” of 1876-1878 disrupted the entire tropical monsoon belt, as well as the East Asian and Arabian Monsoons that provide rainfall for North China and North Africa. (Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts).

[10] Jeffrey Snyder-Reinke, Dry Spells: State Rainmaking and Local Governance in Late Imperial China (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009), chapter 4.

[11] Li, Fighting Famine, chapter 8; Will, chapters 7-8; Will and Wong, chapter 3.

[12] H.M. Morse, The International Relations of the Chinese Empire, vol. 2, (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1918), 312; He Hanwei. Guangxu chunian (1876-79) Huabei de da hanzai (The great Huabei region drought disaster of the early Guangxu period) (Hong Kong: Zhongwen daxue chuban she, 1980), ch. 4.

[13] Shanxi tongzhi, j. 82, 18b-19a. The gazetteer states that 3,402,833 people in Shanxi received relief between 1877 and 1879 and that a total of 10,700,315 taels of relief silver and 1,001,657 shi of relief grain were distributed in the province.

[14] Paul Richard Bohr, Famine in China and the Missionary: Timothy Richard as Relief Administrator and Advocate of National Reform, 1876-1884 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972), 89-90.

[15] Bohr 1972: 187-189, 113-114.

[16] Mary Rankin, Elite Activism and Political Transformation in China: Zhejiang Province, 1865-1911 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986), 142-147.

[17] Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley,“Tough Choices: Grappling with Famine in Qing China, the British Empire, and Beyond.” Journal of World History Vol. 24, No. 1 (March 2013): 166-169.

[18] Rankin, Elite Activism, chapter 4; Zhu Hu, Difangxing liudong ji qi chaoyue: wan Qing yizhen yu jindai Zhongguo de xinchen daixie (The fluidity and transcendence of localism: Late-Qing charitable relief and the supersession of the old by the new in modern China) (Beijing: Zhongguo renmin daxue chubanshe, 2006); Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, chapter 6; Andrea Janku, “The North-China Famine of 1876-1879: Performance and Impact of a Non-Event,” 2001 online publication.

[19] Henrietta Harrison,“Newspapers and Nationalism in Rural China, 1890-1929,” Past and Present 166 (1999): 182.

[20] Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, chapter 8.

[21] Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, chapter 9.

[22] Xia Mingfang, “Cong Qingmo zaihai qun faqi kan Zhongguo zaoqi xiandaihua de lishi tiaojian: zaihuang yu Yangwu Yundong yanjiu zhi yi,” (Looking at the historical conditions for China’s early modernization from the rise of late-Qing disasters: Part I of research on disasters and the Westernization Movement) Qingshi yanjiu (January 1998): 70. See also Xia Mingfang, “Zhongguo zaoqi gongyehua jieduan yuanshi jilei guocheng de zaihai shi fenxi” (An analysis of the impact of natural disasters on primitive accumulation during the early stages of industrialization in China), Qingshi yanjiu 1 (1999): 62-81.

[243 Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts, 291.

[24] Davis, 9; 15-16; chapter 11.

[25] Andrea Janku, “Sowing Happiness: Spiritual Competition in Famine Relief Activities in Late Nineteenth-Century China.” Minsu Quyi 143 (March 2004): 89-118.

原件資料

British Parliamentary Papers. “Report on the Famine in the Northern Provinces of China.” Irish University Press Area Studies Series. China, 42.2 (1878): 119-150.

Celestial Empire: A Journal of Native and Foreign Affairs in the Far East. Shanghai, 1876-1880.

China’s Millions. China Inland Mission. London, 1877-1881. Includes Report of R.J. Forrest (1879) and Report of Walter C. Hillier (1880).

“Chouban ge sheng huangzheng an” (Proposals for preparing famine relief policies for each province). In Guojia tushuguan cang Qingdai guben neige liubu dangan, compiled by Sun Xuelei and Liu Jiaping. Beijing: Quanguo tushuguan wenxian suowei fuzhi zhongxin, 2003, 38: 18455-963.

“Chouban ge sheng huangzheng an chaodang mulu” (Catalogue of proposals for preparing famine relief policies for each province). In Guojia tushuguan cang Qingdai guben neige liubu dangan, compiled by Sun Xuelei and Liu Jiaping. Beijing: Quanguo tushuguan wenxian suowei fuzhi zhongxin, 2003, 37: 18375-413.

Chronicle of the London Missionary Society for the year 1878. (London, 1878).

Committee of the China Famine Relief Fund. The Famine in China: Illustrations by a Native Artist with a Translation of the Chinese Text. Translated by James Legge. London: C. Kegan Paul & Co., 1878.

Dezong shilu (Veritable records of the Guangxu emperor), part 2. In Qing shilu (Veritable records of the Qing), vol. 53. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1987.

Forrest, R.J. “Report of R.J. Forrest, Esq., H.B.M. Consul at Tien-tsin, and Chairman of the Famine Relief Committee at Tien-tsin.” In China’s Millions (November, 1879): 134-139.

Gordon, C.A. An Epitome of the Reports of the Medical Officers to the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service from 1871 to 1882. London: Bailliere, Tindall, and Cox, 1884.

Guangxu chao Donghualu (Guangxu reign period [1875-1908] records from the Eastern Gate), 5 vols. Zhu Shoupeng, comp., 1909. Reprint, Beijing: Zhonghua shuju chubanshe, 1958.

Hejian xianzhi (Gazetteer of Hejian county). 1880.

Hill, David. Papers and Letters. Methodist Missionary Society collection. School of Oriental and African Studies Library Archives and Manuscripts, London.

Hillier, Walter C. “Report of Walter Hillier, Esq., H.M.B Consular Service,” submitted to the chairman of the China Famine Relief Committee in Shanghai. In North China Herald and Supreme Court and Consular Gazette, 15 April 1879. The Hillier report was also published in full in China’s Millions (1880), 4-8, 20-24.

Hongtong xianzhi (Gazetteer of Hongtong county). 1917. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 79. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Jing Yuanshan. Juyi chuji (Dwelling in leisure, first collection). 3 vols. Shanghai, 1902.

Legge, James, trans. The Famine in China: Illustrations by a Native Artist with a Translation of the Chinese Text. London: Kegan Paul & Co., 1879.

Liang Peicai (Qing). “Shanxi miliang wen” [A Shanxi essay on grain], in Guangxu sannian nian jinglu. Taiyuan: Shanxi sheng remin weiyuan hui bangong ting, 1961.

Linfen xianzhi (Gazetteer of Linfen county). 1933. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi

congshu 415. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Linjin xianzhi (Gazetteer of Linjin county). 1923. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 420. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1976.

Liu Xing (Qing). “Huangnian ge” (Song of the famine years). 1897. Edited version published in Yuncheng zaiyi lu (Record of disasters in Yuncheng), compiled and edited by Zhang Bowen and Wang Mancang, 105-114. Yuncheng: Yuncheng shizhi ban, 1986. Unedited manuscript copy owned by Mr. Nan Xianghai.

Min Erchang (comp.), Beizhuan jibu [Supplementary collection of stele biographies], 1923, in reprint, Qingdai zhuanji congkan 123. Taibei: 1985.

Missionary Herald, The. Baptist Missionary Society, 1876-1881. London.

North China Herald and Supreme Court and Consular Gazette. Shanghai, 1876-1879.

Peking Gazette (Jingbao). Excerpts translated by the North China Herald, and excerpts reprinted in the Shenbao. Shanghai, 1876-1880.

Pinglu xian xuzhi (A continuation of the gazetteer of Pinglu county). 1932. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 426. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Pingyao xianzhi (Gazetteer of Pingyao county). 1883.

Qi Yu Jin Zhi zhenjuan zhengxin lu (Statement of accounts for relief contributions for Shandong, Henan, Shanxi, and Zhili), n.p., 1881.

Qing Guangxu chouban gesheng huangzheng dang’an (Guangxu-period famine relief policy archives for each province). Compiled by Chen Zhanqi. Beijing: Quanguo tushuguan wenxian suowei zhongxin, 2008.

“Report on the Famine in the Northern Provinces of China.” In Irish University Press Area Studies Series British Parliamentary Papers. China, 42.2 (1878): 1-19.

Richard, Timothy. Forty-five Years in China: Reminiscences. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1916.

Shanxi tongzhi (Gazetteer of Shanxi Province). Compiled by Zeng Guoquan and Wang Xuan. 1892.

“Si sheng gao zai tu qi,” shou juan (Pictures reporting the disaster in the four provinces, opening volume). In Qi Yu Jin Zhi zhenjuan zhengxin lu (Statement of accounts for relief contributions for Shandong, Henan, Shanxi, and Zhili). n.p., 1881.

Shenbao (The Shenbao Daily News). Shanghai, 1876-1881.

Sun Anbang, comp. Qing shilu: Shanxi ziliao huibian (Veritable Records of the Qing Dynasty: A compilation of materials regarding Shanxi). 3 vols. Taiyuan: Shanxi guji chubanshe, 1996.

Wang Xilun, Yiqingtang wenji (1912).

Wanrong xianzhi (Gazetteer of Wanrong county). Beijing: Haichao chubanshe, 1995.

Wu Jun. Collection of rubbings of stele inscriptions from the Yuncheng area, held in the Yuncheng shi Hedong bowuguan (Yuncheng City Hedong Museum). Yuncheng, Shanxi.

Xia xianzhi (Gazetteer of Xia county). 1880.

Xie xianzhi (Gazetteer of Xie county). 1920. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 84. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Xiezhou Ruicheng xianzhi (Gazetteer of Xie department, Ruicheng county). 1880.

Xu Yishi xianzhi (A continuation of the gazetteer of Yishi county). 1880.

Xuxiu Jiangzhou zhi (A continued and revised gazetteer of Jiang department). 1879.

Xuxiu Jishan xianzhi (A continued and revised gazetteer of Jishan county). 1885.

Xuxiu Linjin xianzhi (A continued and revised gazetteer of Linjin county). 1880.

Xuxiu Quwo xianzhi (A continued and revised gazetteer of Quwo county). 1880.

Xuxiu Xizhou zhi (A continued and revised gazetteer of Xi department). 1898. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 428. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1976.

Yicheng xianzhi (Gazetteer of Yicheng county). 1929. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 417. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Yonghe xianzhi (Gazetteer of Yonghe county). 1931. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 88. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Yongji xianzhi (Gazetteer of Yongji county). 1886.

Zeng Guoquan. Zeng Zhongxiang gong (Guoquan) shuzha (Zeng Guoquan’s correspondence). Compiled by Xiao Rongjue, 1903.

_____. Zeng Zhongxiang gong (Guoquan) zouyi (Zeng Guoquan’s memorials). Compiled by Xiao Rongjue, 1903. Reprinted in Jindai Zhongguo shiliao congkan (Modern Chinese Historical Materials) 44, edited by Shen Yunlong. Taipei: Wenhai chubanshe, 1969.

Zheng Guanying. Jiuhuang fubao (Good fortune received as recompense for famine relief). 1878. Reprint, 1935.

______. Zheng Guanying ji, (Collected works of Zheng Guanying), 2 vols. Edited by Xia Dongyuan. Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1982.

媒體

Pingyao County Historical Relics Bureau, “Xian Taiye Bai Chenghuang: Xiju Xiaopin” (The county magistrate pays respects to the City God: A short drama), unpublished manuscript, 2001.

書目

Barber, W.T.A. David Hill: Missionary and Saint. London: Charles H. Kelly, 1898.

Bohr, Paul Richard. Famine in China and the Missionary: Timothy Richard as Relief Administrator and Advocate of National Reform, 1876-1884. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Chai Jiguang. “Xuelei banban shi leshi zhu houren: Du Guangxu sannian zaiqing beiwen zhaji” (Blood-tears affairs carved into stone to exhort later people: Commentary on reading stele inscriptions concerning disaster conditions in Guangxu 3). Hedong shike yanjiu (Hedong stone stele research), first issue (1994): 33-37.

Chen Yongqin. “Wan Qing Qingliu pai de xumin sixiang” (The late-Qing Qingliu group’sideology of relieving the people). Lishi dangan 2 (2003): 105-112.

Cohen, Paul. History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World. London: Verso, 2001.

Deng Yunte. Zhongguo jiuhuang shi (The history of famine relief in China). Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan gufen youxian gongsi, 1970.

Dunstan, Helen. Conflicting Counsels to Confuse the Age: A Documentary Study of Political Economy in Qing China, 1644-1840. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, 1996.

Eastman, Lloyd. “Ch’ing-I and Chinese Policy Formation during the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Asian Studies 24.4 (August 1965): 595-611.

Edgerton-Tarpley, Kathryn. “Chinese Responses to Disaster: A View from the Qing,” originally appeared on the China Beat blog (5/19/2008), reprinted in Kate Merkel-Hess, Kenneth L. Pomeranz, and Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom, eds., China in 2008: A Year of Great Significance. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Press, 2009, pp. 101-104.

______. “Family and Gender in Famine: Cultural Responses to Disaster in North China, 1876-1879,” Journal of Women’s History (Vol. 16, No. 4, 2004), pp. 119-147.

______. “From ‘Nourish the People’ to ‘Sacrifice for the Nation’: Changing Responses to Disaster in Late Imperial and Modern China.” The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 73, No. 2 (May 2014): 447-469.

______. “‘Governance with Government:’ Non-State Responses to the North China Famine of 1876-1879,” Chinese History and Society/Berliner China-Hefte (Vol. 35, 2009): 33-47.

______. “Pictures to Draw Tears from Iron: Depicting Disaster and Raising Relief Funds during the North China Famine of 1876-1879,” unit for Visualizing Cultures project, MIT. Published on MIT OpenCourseWare (visualizingcultures.mit.edu), spring 2011.

______. Tears from Iron: Cultural Responses to Famine in Nineteenth-Century China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008. Chinese edition: 铁泪图: 19 世纪中国对于饥馑的文化反应, translated by Cao Xi 曹曦. Nanjing: Jiangsu People’s Publishing House, 2011.

______. “The ‘Feminization of Famine,’ The Feminization of Nationalism: Famine and Social Activism in Treaty-port Shanghai, 1876-1879,” Social History, (Vol. 30, No. 4, November 2005), pp. 421-443.

______. “The Semiotics of Starvation in Late-Qing China: Cultural Responses to the “Incredible Famine” of 1876-1879.” Ph.D. Diss., Indiana University, 2002.

______. “Tough Choices: Grappling with Famine in Qing China, the British Empire, and Beyond.” Journal of World History Vol. 24, No. 1 (March 2013): 135-176.

______. “WanQing Zhongguo de zaihuang yu yishi xingtai – 1876-1879 nian ‘Dingwu qihuang’ qijian guanyu zaihuang chengyin he fanghai wenti de duilixing chanshi (Famine and ideology in Late-Qing China: Contending interpretations of famine causation and prevention during the ‘Incredible Famine’ of 1876-1879,”) in Li Wenhai and Xia Mingfang, eds., Tian you xiongnian: Qingdai zaihuang yu Zhongguo shehui (Years of Disaster: Natural Calamities and Chinese Society during the Qing Dynasty). Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 2007, pp. 509-537.

Elvin, Mark. “Who Was Responsible for the Weather? Moral Meteorology in Late Imperial China.” Osiris 12 (1998): 213-237.

Feng Jinniu. “Sheng Xuanhuai dang’an zhong de Zhongguo jindai zaizhen shiliao” (The Sheng Xuanhuai Archives: Modern China’s disaster relief materials). Qingshi Yanjiu 3 (2000): 94-100.

Grady, Lolan Wang. “The Career of I-Hsin, Prince Kung, 1858-1880: A Case-Study of the Limits of Reform in the Late Ch’ing.” PhD diss., University of Toronto, 1980.

Guangxu sannian nianjing lu (Annual record of the third year of the Guangxu reign). Taiyuan: Shanxi sheng remin weiyuanhui bangong ting, 1961.

Guangxu sannian nianjing lu, xubian (Annual record of the third year of the Guangxu reign, continuation). Taiyuan: Shanxi sheng renmin weiyuanhui bangong ting, 1962.

Hao Ping. Dingwu Qihuang: Guangxu chunian Shanxi zaihuang yu jiuji yanjiu (The Incredible Famine of 1877-78: Research on the early Guangxu-period Shanxi famine and famine relief). Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 2012.

Harrison, Henrietta. The Man Awakened from Dreams: One Man’s Life in a North China Village, 1857-1942. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005.

______. The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

______. “Newspapers and Nationalism in Rural China, 1890-1929.” Past and Present 166 (1999): 181-204.

He Hanwei. Guangxu chunian (1876-79) Huabei de da hanzai (The great Huabei region drought disaster of the early Guangxu period). Hong Kong: Zhongwen daxue chuban she, 1980.

Horowitz, Richard. “Central Power and State-Making: The Zongli Yamen and Self-Strengthening in China, 1860-1880.” Ph. D. diss., Harvard University, 1998.

Janku, Andrea. “’Heaven-Sent Disasters’ in Late Imperial China: the Scope of the State and Beyond,” in Mauch, Christof and Pfister, Christian, eds. Natural Disasters, Cultural Responses: Case Studies Toward a Global Environmental History. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2009, pp. 233-264.

______. “Sowing Happiness: Spiritual Competition in Famine Relief Activities in Late Nineteenth-Century China.” Minsu Quyi 143 (March 2004): 89-118.

______. “The North-China Famine of 1876-1879: Performance and Impact of a Non-Event,” in Measuring Historical Heat: Event, Performance, and Impact in China and the West. Symposium in Honour of Rudolf G. Wagner on His 60th Birthday. (Heidelberg, November 3rd-4th, 2001, online publication).

_______. “Towards a History of Natural Disasters in China: The Case of Linfen County.” The Medieval History Journal 10 (2007): 267-301.

_______. “Wei Huabei jihuang zuo zheng: jiedu Xiangling xianzhi ‘zhenwu’ juan (Documenting the North-China Famine: The chapter on relief affairs in the Xiangling xianzhi), in Li Wenhai and Xia Mingfang, eds., Tian you xiongnian: Qingdai zaihuang yu Zhongguo shehui (Years of Disaster: Natural Calamities and Chinese Society during the Qing Dynasty). Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 2007, pp. 479-508.

________. “What Chinese Biographies of Moral Exemplars Tell Us about Disaster Experiences (1600-1900), in Summermatter, Stephanie, et al., ed., Nachhaltige Geschichte: Festschrift für Christian Pfister. Zürich: Chronos, 2009, pp. 129-148.

Kaiser, Andrew T. “Encountering China: The Evolution of Timothy Richard’s Missionary Thought (1870-1891).” Ph.D. diss., University of Edinburgh, 2014.

Li Fubin. “Qingdai zhonghouqi Zhili Shanxi chuantong nongyequ kenzhi shulun” (An account of land reclamation in the traditional agricultural areas of Zhili and Shanxi during the mid and late Qing). Zhongguo lishi dili luncong 2 (1994): 147-166.

Li, Lillian M. Fighting Famine in North China: State, Market, and Environmental Decline, 1690s-1990s. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

______. “Introduction: Food, Famine, and the Chinese State.” Journal of Asian Studies 41.4 (August 1982): 687-707.

Li Wenhai. Jindai Zhongguo zaihuang jinian (A chronological record of disasters in Modern China). Hunan: Hunan jiaoyu chubanshe, 1990.

______, Cheng Xiao, Liu Yangdong, and Xia Mingfang. Zhongguo jindai shi da zaihuang (The ten great famines of China’s modern period). Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1994.

______ and Xia Mingfang, editors. Tian you xiongnian: Qingdai zaihuang yu Zhongguo shehui (Years of Disaster: Natural Calamities and Chinese Society during the Qing Dynasty). Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 2007.

______ and Zhou Yuan. Zaihuang yu jijin. Beijing: Xinhua shudian, 1991.

Liu Fengxiang. “Qianxi ‘Dingwu qihuang’ de yuanyin” (A brief analysis of the causes of the ‘Incredible Famine of 1877-78”). Jining shizhuan xuebao 4 (2000): 1-3.

Liu Rentuan. “‘Dingwu qihuang’ dui Shanxi renkou de yingxiang (The influence of the ‘incredible famine of 1877-78’ on Shanxi’s population). In Ziran zaihai yu Zhongguo shehui lishi jiegou (Natural disasters and social structure in Chinese history), edited by Institute of Chinese Historical Geography, Fudan University, 91-131. Shanghai: Fudan daxue chubanshe, 2001.

Mallory, Walter H. China: Land of Famine. New York: American Geographical Society, 1926.

Mittler, Barbara. A Newspaper for China? Power, Identity, and Change in Shanghai’s News Media (1872-1912). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Nathan, Andrew J. A History of the China International Famine Relief Commission. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965.

Peking United International Famine Relief Committee. The North China Famine of 1920-1921, With Special Reference to the West Chili Area. 1922. Reprint, Taipei: Ch’eng-wen Publishing Company, 1971.

Pomeranz, Kenneth. The Making of a Hinterland: State, Society, and Economy in Inland North China, 1853-1937. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Rankin, Mary. Elite Activism and Political Transformation in China: Zhejiang Province, 1865-1911. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986.

______. “‘Public Opinion’ and Political Power: Qingyi in Late Nineteenth Century China.” Journal of Asian Studies 41.3 (May 1982): 453-484.

Read, Bernard E. Famine Foods Listed in the Chiu Huang Pen Ts’ao. Taipei: Reprinted by Southern Materials Center, Inc., 1982.

Snyder-Reinke, Jeffrey. Dry Spells: State Rainmaking and Local Governance in Late Imperial China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009.

Tao Fuhai. “Qing Guangxu Dingchou Jin, Shaan, Yu da han kuixi” (Analyzing the great drought in Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Henan in the third year of the Guangxu reign). In Pingyang minsu congtan (A collection of Pingyang folk customs). Taiyuan: Shanxi guji chubanshe, 1995.

Tsu Yu-yue. The Spirit of Chinese Philanthropy: A Study on Mutual Aid. New York, AMS Press, 1912.

Wagner, Rudolf. “The Role of the Foreign Community in the Chinese Public Sphere.” China Quarterly 142 (June 1995): 421-443.

Wang Jingxiang. “Shanxi ‘Dingwu qihuang’ luetan” (A brief exploration of the “Incredible Famine of 1877-78” in Shanxi). Zhongguo nongye shi 3 (1983): 21-29.

Wang Yongnian and Jie Fuping. “Dingchou zhenzai ji” (Record of famine relief in 1877). Yuncheng wenshi ziliao (Yuncheng literary and historical materials) 2 (1988): 97-125.

Watkins, Susan Cotts, and Jane Menken. “Famines in Historical Perspective.” Population and Development Review 11.4 (1985): 647-675.

Will, Pierre-Etienne. Bureaucracy and Famine in Eighteenth-Century China. Translated by Elborg Forster. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990.

______ and R. Bin Wong. Nourish the People: The State Civilian Granary System in China, 1650-1850. With James Lee, Jean Oi and Peter Perdue. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, 1991.

Wong, R. Bin. China Transformed: Historical Change and the Limits of European Experience. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997.

______. “Food Riots in the Qing Dynasty.” Journal of Asian Studies 41.4 (1982): 767-788.

Wu Jun. “Shanxi shike yanjiuhui Yuncheng diqu fenhui choubei gongzuo qingkuang huibao” (Report on the preparatory work situation of the Yuncheng area branch society of the Shanxi stone carvings research association). Hedong shike yanjiu (Hedong stone carvings research), first issue (1994): 5-7, 28-32.

Wue, Roberta. “The Profits of Philanthropy: Relief Aid, Shenbao, and the Art World in Later Nineteenth-Century Shanghai.” Late Imperial China 25.1 (June 2004): 187-211.

Xia Dongyuan. Zheng Guanying zhuan (Biography of Zheng Guanying). Shanghai: Huadong shifan daxue chuban she, 1985.

Xia Mingfang. “Cong Qingmo zaihai qun faqi kan zhongguo zaoqi xiandaihua de lishi tiaojian: zaihuang yu Yangwu Yundong yanjiu zhiyi” (Looking at the historical conditions of China’s early modernization as initiated by the cluster of late-Qing disasters: Part I of research on disasters and the Westernization Movement). Qingshi yanjiu 1 (1998): 62-81.

______. “Qingji ‘Dingwu qihuang’ de zhenji ji shanhou wenti chutan” (An initial exploration of the relief and reconstruction problems during the Qing-era “Incredible Famine of 1877-78”). Jindaishi yanjiu 2 (1993): 1-36.

______. “Zhongguo zaoqi gongyehua jieduan yuanshi jilei guocheng de zaihai shi fenxi” (An analysis of the impact of natural disasters on primitive accumulation during the early stages of industrialization in China). Qingshi yanjiu 1 (1999): 62-81.

Xu Zaiping and Xu Ruifang. Qingmo sishinian Shenbao shiliao (Materials on the Shenbao in the last forty years of the Qing). Beijing: Xinhua chubanshe, 1988.

Yang Jianli. “Wan Qing shehui zaihuang jiuzhi gongneng de yanbian: yi ‘Dingwu qihuang’ de liang zhong zhenji fangshi wei li” (Changes in social disaster relief in the Late Qing: Taking the two kinds of relief methods during the “Incredible Famine of 1877-78” as an example). Qingshi yanjiu 4 (2000): 59-76.

Yuanqu wenshi ziliao (Yuanqu literary and historical materials) 4 (1988), compiled by Zhongguo renmin zhengzhi xieshang huiyi Yuanqu xian weiyuanhui (The Yuanqu county committee of the Chinese people’s political consultative conference).

Yuncheng shi bowuguan bian (Yuncheng city museum publication), compiled by Wang Zhangbao. Yuncheng, 1989.

Yuncheng zaiyi lu (Record of disasters in Yuncheng). Compiled and edited by Zhang Bowen and Wang Mancang. Yuncheng: Yuncheng shizi ban, 1986.

Zhang Jie. Shanxi ziran zaihaishi nianbiao, 730 B.C. – 1985 A.D. (A yearly record of Shanxi’s natural disasters). Taiyuan: Shanxi sheng chubanshi, 1988.

Zhang Kemin, ed. “Zhongguo jindai zaihuang yu shehui wending” (Disasters in Modern China and social stability). In Zhongwai lishi wenti ba ren tan (An eight person discussion of questions in Chinese and foreign history), 158-206. Beijing: Guojia jiaowei gaojiao shehui kexue fazhan yanjiu zhongxin, 1998.

Zhao Lianyue. “Renhuo jiazhong le tianzai: 1876-1879 nian ‘Dingwu qihuang’ bianxi” (Man-made disaster adds to natural disaster: critical analysis of the 1876-1879 “Incredible Famine”). Guangxi Youjiang minzu shifan gaodeng zhuanke xuexiao xuebao 12.1 (1999): 41-43.

Zhao Shiyuan. “’Dingwu qihuang’ shulue” (An account of the “Incredible Famine of 1877-78). Xueshu yuekan 141.2 (1981): 65-68.

Zheng Guosheng. “Yipian beiwen” (One stele inscription). Zhongguo qingnian 5 (1961): 33-34.

Zhu Hu. Difangxing liudong ji qi chaoyue: wan Qing yizhen yu jindai Zhongguo de xinchen daixie (The fluidity and transcendence of localism: Late-Qing charitable relief and the supersession of the old by the new in modern China). Beijing: Zhongguo renmin daxue chubanshe, 2006.