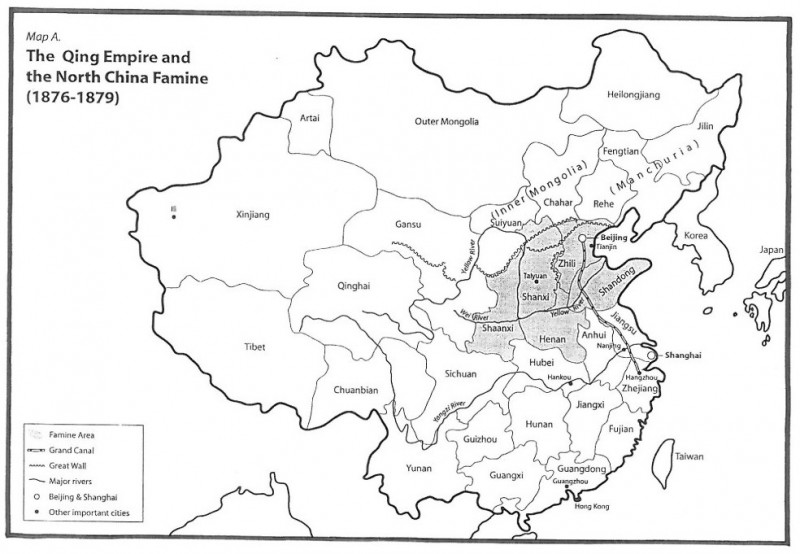

Between 1876 and 1879, the most lethal drought-famine in imperial China’s long history of famines and disasters struck the five northern provinces of Shandong, Zhili, Shanxi, Henan, and Shaanxi. The drought in the Yellow River basin area began in earnest in 1876, and worsened dramatically with the almost total failure of rain in 1877. By the time conditions began to stabilize in 1879, an estimated 9.5 to 13 million of the affected area’s total population of about 108 million people had perished of starvation and famine-related diseases.[1]

CAUSATION

The severe drought that struck North China in the late 1870s was the catalyst but not the underlying cause of the Incredible Famine. In a vast and highly commercialized economy like Qing China’s, a serious regional dearth did not have to result in a major famine. During the eighteenth century, when the Qing state’s power and commitment to storing and distributing grain were at their apex, the state on several occasions effectively prevented serious droughts from resulting in mass starvation.[2] In contrast, by the late nineteenth century the Qing state had been considerably weakened by the mid-century rebellions, fiscal crisis, a lack of strong leadership, and the pressure of foreign imperialism. It thus was no longer able to muster the degree of intervention necessary to prevent the drought from causing a famine.

The mid-century rebellions that began in the 1850s depleted both national and provincial resources to dangerous levels, leaving the state woefully ill-prepared to deal with a major drought. The combined fiscal impact of the Taiping Rebellion (1851-1864), the Nian Rebellion (1853-1868) and the Muslim Revolts (1855-1873) was enormous. According to some calculations, military expenses constituted nearly three-fourths of the total expenditure of the government. The Taiping war devastated some of China’s richest Yangzi valley provinces and cut off the capital from the land tax and salt monopoly revenue of thirteen provinces. Simultaneously, the Nian rebels disrupted administration in large sections of four northern provinces, and the Muslim revolts in the southwest and the northwest depopulated entire areas.[3] The monumental effort expended to suppress the mid-century rebellions wreaked havoc on the Qing granary system. Especially in the drought-prone northern provinces, Qing officials relied on state and community granaries to keep grain prices down and to provide emergency relief during subsistence crises. The decline of the granary system began in the 1790s and reached crisis levels after the mid-century rebellions. This decline meant that by the time drought spread across North China in the late 1870s, the Qing state’s first line of defense against serious food crises had for the most part been replaced by a “makeshift” system run by local elites who lacked the state’s power to maintain enormous granary reserves and to carry out vital inter-regional grain transfers.[4]

Fiscal problems also contributed to the late-Qing state’s inability to relieve the drought-stricken provinces in a timely manner. High-Qing officials were able to maintain an effective granary system in large part because of the state’s generous fiscal reserves, which normally remained at or exceeded 20,000,000 taels during the eighteenth century. By the time drought struck North China in the 1870s, the Qing treasury had suffered major reversals. The decline in fiscal reserves began in the late eighteenth century, when the state had to spend about 100,000,000 taels to suppress the White Lotus Rebellion of 1796-1804. By the early nineteenth century, tax collection became more and more difficult, and the imperial clan had grown from 2,000 members in the early-Qing period to 30,000 members whose maintenance cost several million taels a year.[5] As the century progressed, the cost of maintaining the Yellow River dikes grew tremendously because of increasingly serious flooding brought about by ecological destruction.[6] Paying indemnities to victorious Western powers after military confrontations and financing coastal defense projects that aimed to improve China’s ability to repel maritime invaders brought additional fiscal pressures.

The threat posed by western and Japanese imperialists also forced Qing rulers and their ministers to make excruciating choices about how best to use the country’s depleted resources. The country’s humiliating defeat at the hands of the British and the French in the Arrow War of 1856-60 accentuated the danger posed by the West, while the “punitive expedition” that Japan landed on Taiwan in 1874 signaled Japan’s growing willingness to challenge Qing predominance in East Asia. The empire’s northwestern frontier also fell under attack when the rich Ili Valley of modern-day Xinjiang, the Inner-Asian area that Qing emperors had worked so hard to conquer in the mid-eighteenth century, was invaded and occupied by Russia in 1871. The costly military campaign to recover what is today Xinjiang province coincided exactly with the worst years of the Incredible Famine, making it all the more difficult for the state to fund relief efforts for the starving people of North China.[7]

A lack of strong leadership was yet another factor that hindered the late-Qing state’s ability to respond quickly and effectively to the drought. The throne was particularly weak during the Incredible Famine of 1876-1879 due to questions about the legitimacy of the Guangxu emperor’s succession that occurred in 1875, only a year before the great drought began. Bereft of strong guidance from the throne, in the late 1870s it was more difficult than usual for the Qing government to implement a famine policy requiring large-scale expenditures. [8] In sum, the combination of internal rebellions, foreign aggression, fiscal problems, the demise of the granary system, and weakness and division in the top echelons of power left the Qing state unprepared for a drought of the magnitude of the one that struck North China between 1876 and 1879.[9]

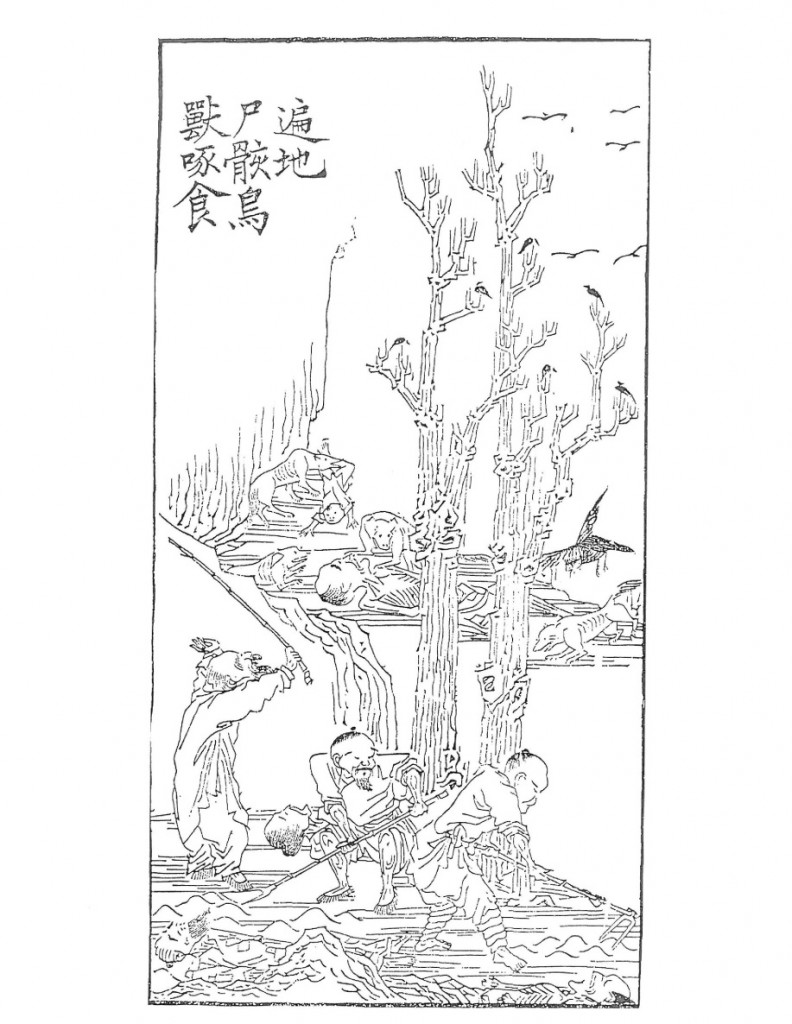

Woodblock Print Illustration: “Unburied Corpses Devoured by Birds and Beasts”

Source: “Si sheng gao zai tu qi,” shou juan (Pictures reporting the disaster in the four provinces, opening volume), in Qi Yu Jin Zhi zhenjuan zhengxin lu (Statement of accounts for relief contributions for Shandong, Henan, Shanxi, and Zhili) (n.p., 1881), 14a. Courtesy of the Shanghai Library.

RESPONSES

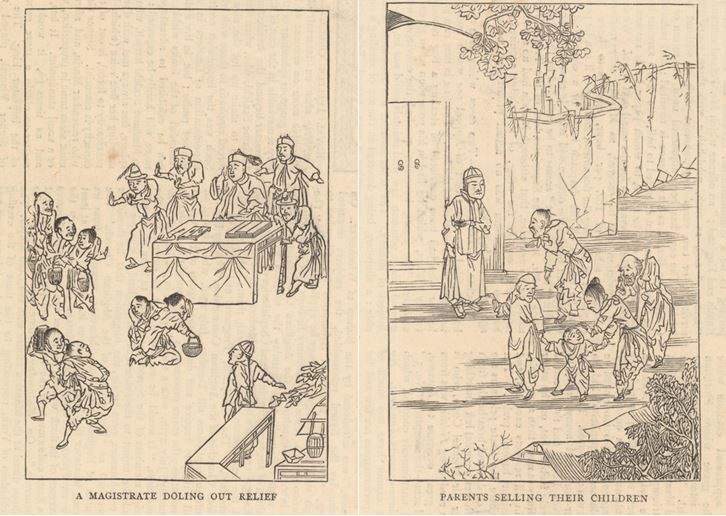

Chinese responses to the North China Famine of 1876-79 both drew on a millennium of traditional Chinese thinking about famine causation and anticipated new issues that would become increasingly important in the Republican and PRC eras. Like their high-Qing predecessors, during the 1870s Qing rulers and officials presented themselves as benevolent parents of the people, and portrayed the famished as suffering children in need of the state’s help. They carried out an array of rituals that aimed to move Heaven to send rain by demonstrating their sincerity and the depth of their concern for the people’s misery.[10] The state also relied on time-honored strategies such as selling state grain at below-market prices (pingtiao) in stricken areas in order to stabilize food prices, reducing or cancelling taxes, investigating affected areas in order to classify households according to their degree of disaster, and working with local elites to open soup kitchens and shelters.[11] The customs official and historian of China H.B. Morse calculated that between 1876 and 1878 the Qing government granted over 18 million taels of tax remissions, which equaled “more than one-fifth of one year’s receipts of the imperial treasury,” to drought-stricken Shanxi, Henan, Shaanxi, and Zhili. The central government also allocated over 5 million taels in direct aid for famine relief, and ordered provinces outside the famine area to loan additional relief money to the drought-stricken provinces.[12] Unlike the high-Qing state, however, in the 1870s the government no longer had the resources and the will to transport and distribute enormous amounts of grain to the stricken population. For example in Shanxi Province, where the famine was most severe, government relief offices dispensed a total of 10.7 million taels of relief silver, but only 1 million shi of relief grain, during the disaster.[13]

Woodblock Print Illustration:

“A Magistrate Doling Out Relief” & “Parents Selling Their Children”

Source: The Graphic (London), July 6, 1878. From the collection of Pierre Fuller.

The severity and scope of the disaster galvanized into action not only the Qing court and the officials in charge of relieving the famished northern provinces, but also Western missionaries and Chinese philanthropists living in the wealthy Jiangnan (lower-Yangzi) region. The catastrophe received widespread coverage in Chinese and English-language newspapers published in the treaty-port of Shanghai. In the spring of 1877, prominent members of the large foreign community in Shanghai responded to missionary appeals for aid by canvassing the foreign settlement for relief donations.[14] In January 1878 the Committee of the China Famine Relief Fund was founded in Shanghai to expand the fund-raising campaign overseas and to supervise the efforts of thirty foreign relief distributors (primarily British and American Protestant missionaries), who dispensed cash relief raised by the Committee to famine sufferers in Shanxi, Shandong, and Zhili. The Committee collected and distributed a total of 204,560 taels of relief funds. At least forty Roman Catholics who were not officially connected to the Shanghai committee also distributed relief.[15]

The late-Qing state’s inability to provide sufficient relief for the drought-stricken northern provinces, combined with critical coverage of the famine in China’s new Western-style newspapers, most importantly the Shanghai-based Shenbao, also spurred the emergence of an extensive famine relief network run by Chinese scholars, merchants, and officials in the Jiangnan region. By the summer of 1878, gentry and merchant relief organizers had established special relief offices (xiezhen gongsuo) in Shanghai, Hangzhou, Suzhou, and Yangzhou. Over the next three years these networks cooperated to raise over a million taels for disaster relief. They cooperated with, but remained separate from, the official relief- coordinating bureau in Tianjin.[16]

CONSEQUENCES

The North China Famine presented a serious crisis for an empire already beleaguered by internal unrest, foreign aggression, and fiscal woes. While Qing rulers and officials never abandoned the rhetoric that championed the State’s responsibility to nourish the people, in actual practice officials were deeply divided over how to divide scarce resources between famine relief and military spending in the late 1870s. One group of powerful officials and Manchu princes wanted to spend China’s limited resources on self-strengthening projects, most notably coastal defense. A second group of influential officials felt that frontier defense in the Northwest, particularly the costly campaign to recover Xinjiang, was even more urgent than maritime defense. Finally, members of a group of lower-ranking metropolitan officials known as the Qingliu (Pure Stream) argued that relieving the famine should be the government’s chief priority. Disagreements between powerful groups of officials hampered the Qing state’s ability to respond to the famine quickly and effectively. A strong and confident emperor might have been able to stop the infighting. Unfortunately, during the late 1870s no one person or group had the authority and confidence to set a clear policy. Instead, the weak Qing Court wavered between the Qingliu perspective that nourishing the people should be a benevolent state’s top priority, and the insistence from self-strengtheners that defending Qing territory from foreign invasion was even more urgent. The debates between self-strengtheners and Qingliu proponents signified a breakdown of consensus over how to interpret a major disaster. By the 1870s, the overall context for understanding the meaning of a famine and the type of response it required was slowly changing from one in which the key issue for rulers was avoiding the charge of losing the Mandate of Heaven, to one that emphasized defending the country from rapacious and increasingly powerful foreign powers.[17]

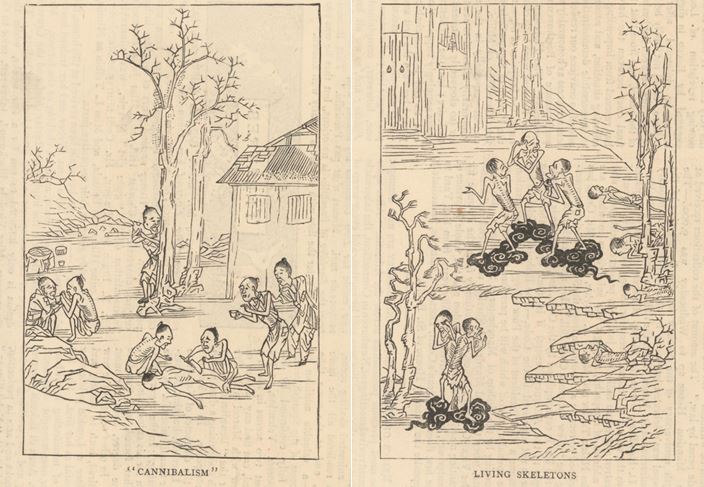

Woodblock Print Illustration:

“Cannibalism” & “Living Skeletons”

Source: The Graphic (London), July 6, 1878. From the collection of Pierre Fuller.

As work by Mary Rankin, Zhu Hu, Andrea Janku, and Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley has demonstrated, the famine also had a significant effect on influential elites in the wealthy Jiangnan region. There the disaster led Chinese philanthropists to move beyond their locale and focus on saving starving strangers in distant North China rather than the poor in their own native places, to compete with the relief activities organized by foreigners, and to take on the responsibility of government officials when the state failed to nourish the people.[18] Among some members of the Jiangnan elite, intense frustration over the Chinese government’s delayed and inadequate relief effort during the disaster also gave rise to critiques of Qing officialdom and loud cries for reform. Faced with a constant barrage of foreign critiques of the Qing government’s relief efforts and with the challenge posed by foreign missionaries who rushed to northern provinces to distribute famine relief, members of Jiangnan’s merchant and literati elite came to view the famine as primarily a national humiliation. Particularly in Shanghai, the famine was one of the major nineteenth-century crises that forced activist members of the treaty-port elite to begin what Joseph Levenson called the transition from “culturalism” to nationalism. As it began entering China from the West in the 1860s, modern nationalism differed from earlier forms of Chinese identity “both in its emphasis on the idea of competition between states and in its rejection of much of what previously constituted Chinese identity.”[19 Foreign critiques and new information about relief efforts overseas and missionary relief campaigns in China forced educated Chinese in Shanghai to wrestle uncomfortably with the possibility that just as China was not “all under heaven” but simply “one country among many,” so Chinese famine relief methods were not “the relief method,” but only one of many different ways of dealing with disaster.[20]

HISTORIOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW

In spite of the considerable national and international attention it received in the 1870s, throughout most of the twentieth-century the North China Famine was all but forgotten by Chinese and foreign scholars alike. It was not until the Mao-era Great Leap Famine of 1958-62, which killed approximately thirty million people, that the horrors of the late 1870s were deliberately drawn back into public memory in China to downplay the PRC state’s total failure to feed the Chinese people. Discussions of the late-Qing famine published in the early 1960s laid the blame for the North China Famine squarely at the foot of rapacious Qing officials, and argued that only in the cannibalistic “old feudal society” did corrupt leaders, rapacious local elites, and a fundamentally flawed social system allow natural disasters to result in mass starvation and even intra-familial cannibalism.[21]

Woodblock Print Illustration:

“Mother and Child Dead From Hunger” & “Starving People Committing Suicide”

Source: The Graphic (London), July 6, 1878. From the collection of Pierre Fuller.

In the 1980s, Chinese historians working on a national-level took a new interest in researching the 1876-79 famine as part of a cluster of major natural disasters that plagued China during the late-Qing period. Post-Cultural Revolution scholarly literature on the North China Famine has shifted away from using the disaster as a prime example of the corruption and heartlessness embedded in the “old feudal society.” One new focal point has been to examine the 1876-79 famine and other late-Qing disasters as possible keys to understanding why China fell behind the West during the nineteenth-century, and why late-Qing efforts to “modernize” come to naught. Historian Xia Mingfang, for example, asserts that the Self Strengthening Movement (1861-1895), which aimed to enrich and strengthen China by fostering industrialization, was seriously hampered by a series of costly and destructive droughts and floods. According to Xia, these disasters drained the Qing treasury, diverted the attention of progressive officials away from modernization efforts, and played a role in impeding primitive capital accumulation and the development of commodity and labor markets in late nineteenth-century China.[22]

Sociologist Mike Davis has taken the discussion of the impact of this famine to a global level. The devastating drought-related famines that struck China, India, Brazil, southern Africa, and Egypt in the late nineteenth century, he argues, were both a symptom and a cause of the transformation of “former ‘core’ regions of eighteenth-century subcontinental power systems” into “famished peripheries of a London-centered world economy.” [23] Davis blames the imperialist imposition of free-market economics on the colonized and semi-colonized world for the staggering death tolls caused by these famines. In the Chinese case, Davis argues, a “drastic decline in state capacity and popular welfare, especially famine relief” followed “in lockstep” with the Qing dynasty’s forced ‘opening’ to modernity by Britain and the other Powers. Borrowing David Arnold’s emphasis on famines as “engines of historical transformation,” Davis asserts that “what we today call the ‘third world’ is the outgrowth of income and wealth inequalities . . . that were shaped most decisively in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when the great non-European peasantries were initially integrated into the world economy.” [24]

Finally, influenced by the rise of cultural history, recent works by Andrea Janku and Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley have examined how cultural and religious ideas shaped Chinese responses to and interpretations of the North China Famine of 1876-79. In one of her articles, for instance, Janku demonstrates that the competition between Western missionaries and Jiangnan philanthropists pursued on a material level in the fund-raising campaigns during the famine was paralleled by a “rivalry on the spiritual level” that contributed in key ways to China’s “Buddhist revival” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[25] Edgerton-Tarpley’s monograph on the famine, Tears from Iron (2008), analyzes disparate cultural and political responses to the disaster. One section of her book examines how villagers in famine-stricken Shanxi, provincial and central-government officials in charge of relief efforts, treaty-port philanthropists, and Anglo-American missionaries and journalists interpreted famine causation and defined moral and immoral responses to mass starvation. The final section examines the key images and stories Chinese observers selected to signify the horror of the famine.

TYPES OF SOURCES

There is a wide array of primary source material on the North China Famine of 1876-79. There are many easily-accessible local sources such as county gazetteers and wenshi ziliao publications, especially for Shanxi Province. Woodblock print illustrations and accompanying laments (see Qi Yu Jin Zhi zhenjuan zhengxin lu in bibliography) designed by Chinese philanthropists in Shanghai and Suzhou are available in the Shanghai Library, and the Shanghai-based Shenbao newspaper provides detailed coverage of the disaster. The perspective of leading provincial and central-government officials can be found in a published collection of famine-related memorials and edicts gathered for use by the Zongli Yamen (see “Chouban ge sheng huangzheng an” in bibliography), and in the Guangxu chao Donghualu. Useful English-language primary sources on the famine include the Shanghai-based North China Herald and Celestial Empire, a lengthy report in the British Parliamentary Papers, and missionary publications such as China’s Millions and Timothy Richard’s Forty-five Years in China.

In terms of secondary sources, book-length studies of the famine published in Chinese include He Hanwei’s Guangxu chunian (1876-79) Huabei de da hanzai (1980), Zhu Hu’s Difangxing liudong ji qi chaoyue: wan Qing yizhen yu jindai Zhongguo de xinchen daixie (2006), and Hao Ping’s Dingwu Qihuang: Guangxu chunian Shanxi zaihuang yu jiuji yanjiu (2014). Book-length studies in English include Paul Richard Bohr’s Famine in China and the Missionary: Timothy Richard as Relief Administrator and Advocate of National Reform, 1876-1884 (1972), and Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley’s Tears from Iron: Cultural Responses to Famine in Nineteenth-Century China (2008). Important articles or book chapters (see bibliography) on this disaster have been published by Xia Mingfang, Li Wenhai, Andrea Janku, Mary Rankin, Lillian M. Li, and Mike Davis.

METRICS

Mortality: Determining famine mortality rates during the North China Famine is difficult. In 1879, the Report of the Committee of the China Famine Relief Fund estimated that 5.5 million people had died in Shanxi, 2.5 million in Zhili, 1 million in Henan, and .5 million in Shandong, for a total of 9.5 million deaths due to starvation and famine-related diseases such as typhus fever and dysentery. Lillian Li observes that the Report’s estimate of 2.5 million deaths in Zhili may be too high, since relief did reach the most severely-affected southern area of the province. On the other hand, the number of deaths in Shanxi may have been even higher (see below), and the Report did not include an estimate for the death toll in Shaanxi Province, which also suffered extensively from the drought. Modern historians have generally estimated the death toll as between 9.5 and 13 million people.

Estimates of famine-related population loss in Shanxi Province, the epicenter of the famine, vary considerably. Foreign relief workers estimated that roughly 5.5 million of Shanxi’s pre-famine population of 15 million people had “perished of famine and the subsequent pestilence.” In contrast, toward the end of the disaster Shanxi’s governor, Zeng Guoquan, wrote that nearly half of the people of Shanxi had died since the disaster began, and that deaths were continuing due to the arrival of epidemic disease. The edition of the Shanxi provincial gazetteer compiled shortly after the famine under Zeng Guoquan’s order and published in 1892 stated that based on the province’s population registers, no fewer than 10 million people died during the famine. Liu Rentuan’s recent gazetteer-based study of the impact that the famine had on Shanxi’s population from 1877 through 1953 finds that both the province’s pre-famine population and the level of population loss were higher than the foreign estimates but lower than Zeng Guoquan’s. Liu states that Shanxi’s population dropped from 17.2 to 9.6 million people between 1876 and 1880—an astounding 44.2 percent population loss. Unfortunately, it is impossible to use the gazetteer records to ascertain how many of Shanxi’s missing millions actually died during the famine and how many of them migrated to other areas.

Geographic Scope: The drought and famine affected the five northern provinces of Shandong, Zhili, Shanxi, Henan, and Shaanxi, which encompassed an area of approximately 300,000 square miles.

Affected population: The roughly 108 million people in the five northern provinces affected by the drought.

Duration: Three years — summer of 1876 to summer of 1879. The worst period was 1877-78. The drought began in Shandong and Zhili, and then spread to Shanxi, Henan, and Shaanxi.

Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley is Associate Professor of Late Imperial and Modern Chinese History at San Diego State University

NOTES

[1] R.J. Forrest, “China Famine Relief Fund” (Shanghai, 1879), 1, 9; Susan Cotts Watkins and Jane Menken, “Famines in Historical Perspective,” Population and Development Review 11 (1985): 650.

[2] Pierre-Etienne Will, Bureaucracy and Famine in Eighteenth-Century China, trans. Elborg Forster (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990); Lillian M. Li, Fighting Famine in North China: State, Market, and Environmental Decline, 1690s-1990s (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), chapter 8.

[3] Pao Chao Hsieh, The Government of China, 1644-1911, (Baltimore: The Johns Hpkins Press, 1925), 205-206, 214; Philip A. Kuhn, “The Taiping Rebellion,” in The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 10, 264-316.

[4] Pierre-Etienne Will and R. Bin Wong, Nourish the People: The State Civilian Granary System in China, 1650-1850 (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, 1991); Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World (London: Verso, 2001).

[5] Will, Bureaucracy and Famine, 290-92.

[6] Li, Fighting Famine, chapters 2 and 9; Will, Bureaucracy and Famine, 292-93.

[7] Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron: Cultural Responses to Famine in Nineteenth-Century China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 28-39, 92-102. The Xinjiang campaign cost 52.3 million taels between 1875 and 1881. Xinjiang became a full-fledged Chinese province only in 1884.

[8] Richard Horowitz, “Central Power and State-Making: The Zongli Yamen and Self-Strengthening in China, 1860-1880,” (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1998), 105-106.

[9] Mike Davis demonstrates convincingly that the cause of the severe droughts that impacted places as diverse as northern China, India, southern Africa, and northeastern Brazil in the late 1870s was a particularly powerful “El Nino event,” or a rapid warming of the eastern tropical Pacific that led to the prolonged and virtually complete failure of the monsoons that normally provide rainfall for the affected areas. The grand “El Nino event” of 1876-1878 disrupted the entire tropical monsoon belt, as well as the East Asian and Arabian Monsoons that provide rainfall for North China and North Africa. (Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts).

[10] Jeffrey Snyder-Reinke, Dry Spells: State Rainmaking and Local Governance in Late Imperial China (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009), chapter 4.

[11] Li, Fighting Famine, chapter 8; Will, chapters 7-8; Will and Wong, chapter 3.

[12] H.M. Morse, The International Relations of the Chinese Empire, vol. 2, (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1918), 312; He Hanwei. Guangxu chunian (1876-79) Huabei de da hanzai (The great Huabei region drought disaster of the early Guangxu period) (Hong Kong: Zhongwen daxue chuban she, 1980), ch. 4.

[13] Shanxi tongzhi, j. 82, 18b-19a. The gazetteer states that 3,402,833 people in Shanxi received relief between 1877 and 1879 and that a total of 10,700,315 taels of relief silver and 1,001,657 shi of relief grain were distributed in the province.

[14] Paul Richard Bohr, Famine in China and the Missionary: Timothy Richard as Relief Administrator and Advocate of National Reform, 1876-1884 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972), 89-90.

[15] Bohr 1972: 187-189, 113-114.

[16] Mary Rankin, Elite Activism and Political Transformation in China: Zhejiang Province, 1865-1911 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986), 142-147.

[17] Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley,“Tough Choices: Grappling with Famine in Qing China, the British Empire, and Beyond.” Journal of World History Vol. 24, No. 1 (March 2013): 166-169.

[18] Rankin, Elite Activism, chapter 4; Zhu Hu, Difangxing liudong ji qi chaoyue: wan Qing yizhen yu jindai Zhongguo de xinchen daixie (The fluidity and transcendence of localism: Late-Qing charitable relief and the supersession of the old by the new in modern China) (Beijing: Zhongguo renmin daxue chubanshe, 2006); Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, chapter 6; Andrea Janku, “The North-China Famine of 1876-1879: Performance and Impact of a Non-Event,” 2001 online publication.

[19] Henrietta Harrison,“Newspapers and Nationalism in Rural China, 1890-1929,” Past and Present 166 (1999): 182.

[20] Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, chapter 8.

[21] Edgerton-Tarpley, Tears from Iron, chapter 9.

[22] Xia Mingfang, “Cong Qingmo zaihai qun faqi kan Zhongguo zaoqi xiandaihua de lishi tiaojian: zaihuang yu Yangwu Yundong yanjiu zhi yi,” (Looking at the historical conditions for China’s early modernization from the rise of late-Qing disasters: Part I of research on disasters and the Westernization Movement) Qingshi yanjiu (January 1998): 70. See also Xia Mingfang, “Zhongguo zaoqi gongyehua jieduan yuanshi jilei guocheng de zaihai shi fenxi” (An analysis of the impact of natural disasters on primitive accumulation during the early stages of industrialization in China), Qingshi yanjiu 1 (1999): 62-81.

[243 Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts, 291.

[24] Davis, 9; 15-16; chapter 11.

[25] Andrea Janku, “Sowing Happiness: Spiritual Competition in Famine Relief Activities in Late Nineteenth-Century China.” Minsu Quyi 143 (March 2004): 89-118.

PRIMARY SOURCE BIBLIOGRAPHY

British Parliamentary Papers. “Report on the Famine in the Northern Provinces of China.” Irish University Press Area Studies Series. China, 42.2 (1878): 119-150.

Celestial Empire: A Journal of Native and Foreign Affairs in the Far East. Shanghai, 1876-1880.

China’s Millions. China Inland Mission. London, 1877-1881. Includes Report of R.J. Forrest (1879) and Report of Walter C. Hillier (1880).

“Chouban ge sheng huangzheng an” (Proposals for preparing famine relief policies for each province). In Guojia tushuguan cang Qingdai guben neige liubu dangan, compiled by Sun Xuelei and Liu Jiaping. Beijing: Quanguo tushuguan wenxian suowei fuzhi zhongxin, 2003, 38: 18455-963.

“Chouban ge sheng huangzheng an chaodang mulu” (Catalogue of proposals for preparing famine relief policies for each province). In Guojia tushuguan cang Qingdai guben neige liubu dangan, compiled by Sun Xuelei and Liu Jiaping. Beijing: Quanguo tushuguan wenxian suowei fuzhi zhongxin, 2003, 37: 18375-413.

Chronicle of the London Missionary Society for the year 1878. (London, 1878).

Committee of the China Famine Relief Fund. The Famine in China: Illustrations by a Native Artist with a Translation of the Chinese Text. Translated by James Legge. London: C. Kegan Paul & Co., 1878.

Dezong shilu (Veritable records of the Guangxu emperor), part 2. In Qing shilu (Veritable records of the Qing), vol. 53. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1987.

Forrest, R.J. “Report of R.J. Forrest, Esq., H.B.M. Consul at Tien-tsin, and Chairman of the Famine Relief Committee at Tien-tsin.” In China’s Millions (November, 1879): 134-139.

Gordon, C.A. An Epitome of the Reports of the Medical Officers to the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service from 1871 to 1882. London: Bailliere, Tindall, and Cox, 1884.

Guangxu chao Donghualu (Guangxu reign period [1875-1908] records from the Eastern Gate), 5 vols. Zhu Shoupeng, comp., 1909. Reprint, Beijing: Zhonghua shuju chubanshe, 1958.

Hejian xianzhi (Gazetteer of Hejian county). 1880.

Hill, David. Papers and Letters. Methodist Missionary Society collection. School of Oriental and African Studies Library Archives and Manuscripts, London.

Hillier, Walter C. “Report of Walter Hillier, Esq., H.M.B Consular Service,” submitted to the chairman of the China Famine Relief Committee in Shanghai. In North China Herald and Supreme Court and Consular Gazette, 15 April 1879. The Hillier report was also published in full in China’s Millions (1880), 4-8, 20-24.

Hongtong xianzhi (Gazetteer of Hongtong county). 1917. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 79. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Jing Yuanshan. Juyi chuji (Dwelling in leisure, first collection). 3 vols. Shanghai, 1902.

Legge, James, trans. The Famine in China: Illustrations by a Native Artist with a Translation of the Chinese Text. London: Kegan Paul & Co., 1879.

Liang Peicai (Qing). “Shanxi miliang wen” [A Shanxi essay on grain], in Guangxu sannian nian jinglu. Taiyuan: Shanxi sheng remin weiyuan hui bangong ting, 1961.

Linfen xianzhi (Gazetteer of Linfen county). 1933. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi

congshu 415. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Linjin xianzhi (Gazetteer of Linjin county). 1923. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 420. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1976.

Liu Xing (Qing). “Huangnian ge” (Song of the famine years). 1897. Edited version published in Yuncheng zaiyi lu (Record of disasters in Yuncheng), compiled and edited by Zhang Bowen and Wang Mancang, 105-114. Yuncheng: Yuncheng shizhi ban, 1986. Unedited manuscript copy owned by Mr. Nan Xianghai.

Min Erchang (comp.), Beizhuan jibu [Supplementary collection of stele biographies], 1923, in reprint, Qingdai zhuanji congkan 123. Taibei: 1985.

Missionary Herald, The. Baptist Missionary Society, 1876-1881. London.

North China Herald and Supreme Court and Consular Gazette. Shanghai, 1876-1879.

Peking Gazette (Jingbao). Excerpts translated by the North China Herald, and excerpts reprinted in the Shenbao. Shanghai, 1876-1880.

Pinglu xian xuzhi (A continuation of the gazetteer of Pinglu county). 1932. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 426. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Pingyao xianzhi (Gazetteer of Pingyao county). 1883.

Qi Yu Jin Zhi zhenjuan zhengxin lu (Statement of accounts for relief contributions for Shandong, Henan, Shanxi, and Zhili), n.p., 1881.

Qing Guangxu chouban gesheng huangzheng dang’an (Guangxu-period famine relief policy archives for each province). Compiled by Chen Zhanqi. Beijing: Quanguo tushuguan wenxian suowei zhongxin, 2008.

“Report on the Famine in the Northern Provinces of China.” In Irish University Press Area Studies Series British Parliamentary Papers. China, 42.2 (1878): 1-19.

Richard, Timothy. Forty-five Years in China: Reminiscences. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1916.

Shanxi tongzhi (Gazetteer of Shanxi Province). Compiled by Zeng Guoquan and Wang Xuan. 1892.

“Si sheng gao zai tu qi,” shou juan (Pictures reporting the disaster in the four provinces, opening volume). In Qi Yu Jin Zhi zhenjuan zhengxin lu (Statement of accounts for relief contributions for Shandong, Henan, Shanxi, and Zhili). n.p., 1881.

Shenbao (The Shenbao Daily News). Shanghai, 1876-1881.

Sun Anbang, comp. Qing shilu: Shanxi ziliao huibian (Veritable Records of the Qing Dynasty: A compilation of materials regarding Shanxi). 3 vols. Taiyuan: Shanxi guji chubanshe, 1996.

Wang Xilun, Yiqingtang wenji (1912).

Wanrong xianzhi (Gazetteer of Wanrong county). Beijing: Haichao chubanshe, 1995.

Wu Jun. Collection of rubbings of stele inscriptions from the Yuncheng area, held in the Yuncheng shi Hedong bowuguan (Yuncheng City Hedong Museum). Yuncheng, Shanxi.

Xia xianzhi (Gazetteer of Xia county). 1880.

Xie xianzhi (Gazetteer of Xie county). 1920. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 84. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Xiezhou Ruicheng xianzhi (Gazetteer of Xie department, Ruicheng county). 1880.

Xu Yishi xianzhi (A continuation of the gazetteer of Yishi county). 1880.

Xuxiu Jiangzhou zhi (A continued and revised gazetteer of Jiang department). 1879.

Xuxiu Jishan xianzhi (A continued and revised gazetteer of Jishan county). 1885.

Xuxiu Linjin xianzhi (A continued and revised gazetteer of Linjin county). 1880.

Xuxiu Quwo xianzhi (A continued and revised gazetteer of Quwo county). 1880.

Xuxiu Xizhou zhi (A continued and revised gazetteer of Xi department). 1898. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 428. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1976.

Yicheng xianzhi (Gazetteer of Yicheng county). 1929. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 417. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Yonghe xianzhi (Gazetteer of Yonghe county). 1931. Reprint, Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 88. Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968.

Yongji xianzhi (Gazetteer of Yongji county). 1886.

Zeng Guoquan. Zeng Zhongxiang gong (Guoquan) shuzha (Zeng Guoquan’s correspondence). Compiled by Xiao Rongjue, 1903.

_____. Zeng Zhongxiang gong (Guoquan) zouyi (Zeng Guoquan’s memorials). Compiled by Xiao Rongjue, 1903. Reprinted in Jindai Zhongguo shiliao congkan (Modern Chinese Historical Materials) 44, edited by Shen Yunlong. Taipei: Wenhai chubanshe, 1969.

Zheng Guanying. Jiuhuang fubao (Good fortune received as recompense for famine relief). 1878. Reprint, 1935.

______. Zheng Guanying ji, (Collected works of Zheng Guanying), 2 vols. Edited by Xia Dongyuan. Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1982.

MEDIA

Pingyao County Historical Relics Bureau, “Xian Taiye Bai Chenghuang: Xiju Xiaopin” (The county magistrate pays respects to the City God: A short drama), unpublished manuscript, 2001.

SECONDARY SOURCE BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barber, W.T.A. David Hill: Missionary and Saint. London: Charles H. Kelly, 1898.

Bohr, Paul Richard. Famine in China and the Missionary: Timothy Richard as Relief Administrator and Advocate of National Reform, 1876-1884. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Chai Jiguang. “Xuelei banban shi leshi zhu houren: Du Guangxu sannian zaiqing beiwen zhaji” (Blood-tears affairs carved into stone to exhort later people: Commentary on reading stele inscriptions concerning disaster conditions in Guangxu 3). Hedong shike yanjiu (Hedong stone stele research), first issue (1994): 33-37.

Chen Yongqin. “Wan Qing Qingliu pai de xumin sixiang” (The late-Qing Qingliu group’sideology of relieving the people). Lishi dangan 2 (2003): 105-112.

Cohen, Paul. History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World. London: Verso, 2001.

Deng Yunte. Zhongguo jiuhuang shi (The history of famine relief in China). Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan gufen youxian gongsi, 1970.

Dunstan, Helen. Conflicting Counsels to Confuse the Age: A Documentary Study of Political Economy in Qing China, 1644-1840. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, 1996.

Eastman, Lloyd. “Ch’ing-I and Chinese Policy Formation during the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Asian Studies 24.4 (August 1965): 595-611.

Edgerton-Tarpley, Kathryn. “Chinese Responses to Disaster: A View from the Qing,” originally appeared on the China Beat blog (5/19/2008), reprinted in Kate Merkel-Hess, Kenneth L. Pomeranz, and Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom, eds., China in 2008: A Year of Great Significance. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Press, 2009, pp. 101-104.

______. “Family and Gender in Famine: Cultural Responses to Disaster in North China, 1876-1879,” Journal of Women’s History (Vol. 16, No. 4, 2004), pp. 119-147.

______. “From ‘Nourish the People’ to ‘Sacrifice for the Nation’: Changing Responses to Disaster in Late Imperial and Modern China.” The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 73, No. 2 (May 2014): 447-469.

______. “‘Governance with Government:’ Non-State Responses to the North China Famine of 1876-1879,” Chinese History and Society/Berliner China-Hefte (Vol. 35, 2009): 33-47.

______. “Pictures to Draw Tears from Iron: Depicting Disaster and Raising Relief Funds during the North China Famine of 1876-1879,” unit for Visualizing Cultures project, MIT. Published on MIT OpenCourseWare (visualizingcultures.mit.edu), spring 2011.

______. Tears from Iron: Cultural Responses to Famine in Nineteenth-Century China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008. Chinese edition: 铁泪图: 19 世纪中国对于饥馑的文化反应, translated by Cao Xi 曹曦. Nanjing: Jiangsu People’s Publishing House, 2011.

______. “The ‘Feminization of Famine,’ The Feminization of Nationalism: Famine and Social Activism in Treaty-port Shanghai, 1876-1879,” Social History, (Vol. 30, No. 4, November 2005), pp. 421-443.

______. “The Semiotics of Starvation in Late-Qing China: Cultural Responses to the “Incredible Famine” of 1876-1879.” Ph.D. Diss., Indiana University, 2002.

______. “Tough Choices: Grappling with Famine in Qing China, the British Empire, and Beyond.” Journal of World History Vol. 24, No. 1 (March 2013): 135-176.

______. “WanQing Zhongguo de zaihuang yu yishi xingtai – 1876-1879 nian ‘Dingwu qihuang’ qijian guanyu zaihuang chengyin he fanghai wenti de duilixing chanshi (Famine and ideology in Late-Qing China: Contending interpretations of famine causation and prevention during the ‘Incredible Famine’ of 1876-1879,”) in Li Wenhai and Xia Mingfang, eds., Tian you xiongnian: Qingdai zaihuang yu Zhongguo shehui (Years of Disaster: Natural Calamities and Chinese Society during the Qing Dynasty). Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 2007, pp. 509-537.

Elvin, Mark. “Who Was Responsible for the Weather? Moral Meteorology in Late Imperial China.” Osiris 12 (1998): 213-237.

Feng Jinniu. “Sheng Xuanhuai dang’an zhong de Zhongguo jindai zaizhen shiliao” (The Sheng Xuanhuai Archives: Modern China’s disaster relief materials). Qingshi Yanjiu 3 (2000): 94-100.

Grady, Lolan Wang. “The Career of I-Hsin, Prince Kung, 1858-1880: A Case-Study of the Limits of Reform in the Late Ch’ing.” PhD diss., University of Toronto, 1980.

Guangxu sannian nianjing lu (Annual record of the third year of the Guangxu reign). Taiyuan: Shanxi sheng remin weiyuanhui bangong ting, 1961.

Guangxu sannian nianjing lu, xubian (Annual record of the third year of the Guangxu reign, continuation). Taiyuan: Shanxi sheng renmin weiyuanhui bangong ting, 1962.

Hao Ping. Dingwu Qihuang: Guangxu chunian Shanxi zaihuang yu jiuji yanjiu (The Incredible Famine of 1877-78: Research on the early Guangxu-period Shanxi famine and famine relief). Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 2012.

Harrison, Henrietta. The Man Awakened from Dreams: One Man’s Life in a North China Village, 1857-1942. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005.

______. The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

______. “Newspapers and Nationalism in Rural China, 1890-1929.” Past and Present 166 (1999): 181-204.

He Hanwei. Guangxu chunian (1876-79) Huabei de da hanzai (The great Huabei region drought disaster of the early Guangxu period). Hong Kong: Zhongwen daxue chuban she, 1980.

Horowitz, Richard. “Central Power and State-Making: The Zongli Yamen and Self-Strengthening in China, 1860-1880.” Ph. D. diss., Harvard University, 1998.

Janku, Andrea. “’Heaven-Sent Disasters’ in Late Imperial China: the Scope of the State and Beyond,” in Mauch, Christof and Pfister, Christian, eds. Natural Disasters, Cultural Responses: Case Studies Toward a Global Environmental History. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2009, pp. 233-264.

______. “Sowing Happiness: Spiritual Competition in Famine Relief Activities in Late Nineteenth-Century China.” Minsu Quyi 143 (March 2004): 89-118.

______. “The North-China Famine of 1876-1879: Performance and Impact of a Non-Event,” in Measuring Historical Heat: Event, Performance, and Impact in China and the West. Symposium in Honour of Rudolf G. Wagner on His 60th Birthday. (Heidelberg, November 3rd-4th, 2001, online publication).

_______. “Towards a History of Natural Disasters in China: The Case of Linfen County.” The Medieval History Journal 10 (2007): 267-301.

_______. “Wei Huabei jihuang zuo zheng: jiedu Xiangling xianzhi ‘zhenwu’ juan (Documenting the North-China Famine: The chapter on relief affairs in the Xiangling xianzhi), in Li Wenhai and Xia Mingfang, eds., Tian you xiongnian: Qingdai zaihuang yu Zhongguo shehui (Years of Disaster: Natural Calamities and Chinese Society during the Qing Dynasty). Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 2007, pp. 479-508.

________. “What Chinese Biographies of Moral Exemplars Tell Us about Disaster Experiences (1600-1900), in Summermatter, Stephanie, et al., ed., Nachhaltige Geschichte: Festschrift für Christian Pfister. Zürich: Chronos, 2009, pp. 129-148.

Kaiser, Andrew T. “Encountering China: The Evolution of Timothy Richard’s Missionary Thought (1870-1891).” Ph.D. diss., University of Edinburgh, 2014.

Li Fubin. “Qingdai zhonghouqi Zhili Shanxi chuantong nongyequ kenzhi shulun” (An account of land reclamation in the traditional agricultural areas of Zhili and Shanxi during the mid and late Qing). Zhongguo lishi dili luncong 2 (1994): 147-166.

Li, Lillian M. Fighting Famine in North China: State, Market, and Environmental Decline, 1690s-1990s. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

______. “Introduction: Food, Famine, and the Chinese State.” Journal of Asian Studies 41.4 (August 1982): 687-707.

Li Wenhai. Jindai Zhongguo zaihuang jinian (A chronological record of disasters in Modern China). Hunan: Hunan jiaoyu chubanshe, 1990.

______, Cheng Xiao, Liu Yangdong, and Xia Mingfang. Zhongguo jindai shi da zaihuang (The ten great famines of China’s modern period). Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1994.

______ and Xia Mingfang, editors. Tian you xiongnian: Qingdai zaihuang yu Zhongguo shehui (Years of Disaster: Natural Calamities and Chinese Society during the Qing Dynasty). Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 2007.

______ and Zhou Yuan. Zaihuang yu jijin. Beijing: Xinhua shudian, 1991.

Liu Fengxiang. “Qianxi ‘Dingwu qihuang’ de yuanyin” (A brief analysis of the causes of the ‘Incredible Famine of 1877-78”). Jining shizhuan xuebao 4 (2000): 1-3.

Liu Rentuan. “‘Dingwu qihuang’ dui Shanxi renkou de yingxiang (The influence of the ‘incredible famine of 1877-78’ on Shanxi’s population). In Ziran zaihai yu Zhongguo shehui lishi jiegou (Natural disasters and social structure in Chinese history), edited by Institute of Chinese Historical Geography, Fudan University, 91-131. Shanghai: Fudan daxue chubanshe, 2001.

Mallory, Walter H. China: Land of Famine. New York: American Geographical Society, 1926.

Mittler, Barbara. A Newspaper for China? Power, Identity, and Change in Shanghai’s News Media (1872-1912). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Nathan, Andrew J. A History of the China International Famine Relief Commission. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965.

Peking United International Famine Relief Committee. The North China Famine of 1920-1921, With Special Reference to the West Chili Area. 1922. Reprint, Taipei: Ch’eng-wen Publishing Company, 1971.

Pomeranz, Kenneth. The Making of a Hinterland: State, Society, and Economy in Inland North China, 1853-1937. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Rankin, Mary. Elite Activism and Political Transformation in China: Zhejiang Province, 1865-1911. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986.

______. “‘Public Opinion’ and Political Power: Qingyi in Late Nineteenth Century China.” Journal of Asian Studies 41.3 (May 1982): 453-484.

Read, Bernard E. Famine Foods Listed in the Chiu Huang Pen Ts’ao. Taipei: Reprinted by Southern Materials Center, Inc., 1982.

Snyder-Reinke, Jeffrey. Dry Spells: State Rainmaking and Local Governance in Late Imperial China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009.

Tao Fuhai. “Qing Guangxu Dingchou Jin, Shaan, Yu da han kuixi” (Analyzing the great drought in Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Henan in the third year of the Guangxu reign). In Pingyang minsu congtan (A collection of Pingyang folk customs). Taiyuan: Shanxi guji chubanshe, 1995.

Tsu Yu-yue. The Spirit of Chinese Philanthropy: A Study on Mutual Aid. New York, AMS Press, 1912.

Wagner, Rudolf. “The Role of the Foreign Community in the Chinese Public Sphere.” China Quarterly 142 (June 1995): 421-443.

Wang Jingxiang. “Shanxi ‘Dingwu qihuang’ luetan” (A brief exploration of the “Incredible Famine of 1877-78” in Shanxi). Zhongguo nongye shi 3 (1983): 21-29.

Wang Yongnian and Jie Fuping. “Dingchou zhenzai ji” (Record of famine relief in 1877). Yuncheng wenshi ziliao (Yuncheng literary and historical materials) 2 (1988): 97-125.

Watkins, Susan Cotts, and Jane Menken. “Famines in Historical Perspective.” Population and Development Review 11.4 (1985): 647-675.

Will, Pierre-Etienne. Bureaucracy and Famine in Eighteenth-Century China. Translated by Elborg Forster. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990.

______ and R. Bin Wong. Nourish the People: The State Civilian Granary System in China, 1650-1850. With James Lee, Jean Oi and Peter Perdue. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, 1991.

Wong, R. Bin. China Transformed: Historical Change and the Limits of European Experience. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997.

______. “Food Riots in the Qing Dynasty.” Journal of Asian Studies 41.4 (1982): 767-788.

Wu Jun. “Shanxi shike yanjiuhui Yuncheng diqu fenhui choubei gongzuo qingkuang huibao” (Report on the preparatory work situation of the Yuncheng area branch society of the Shanxi stone carvings research association). Hedong shike yanjiu (Hedong stone carvings research), first issue (1994): 5-7, 28-32.

Wue, Roberta. “The Profits of Philanthropy: Relief Aid, Shenbao, and the Art World in Later Nineteenth-Century Shanghai.” Late Imperial China 25.1 (June 2004): 187-211.

Xia Dongyuan. Zheng Guanying zhuan (Biography of Zheng Guanying). Shanghai: Huadong shifan daxue chuban she, 1985.

Xia Mingfang. “Cong Qingmo zaihai qun faqi kan zhongguo zaoqi xiandaihua de lishi tiaojian: zaihuang yu Yangwu Yundong yanjiu zhiyi” (Looking at the historical conditions of China’s early modernization as initiated by the cluster of late-Qing disasters: Part I of research on disasters and the Westernization Movement). Qingshi yanjiu 1 (1998): 62-81.

______. “Qingji ‘Dingwu qihuang’ de zhenji ji shanhou wenti chutan” (An initial exploration of the relief and reconstruction problems during the Qing-era “Incredible Famine of 1877-78”). Jindaishi yanjiu 2 (1993): 1-36.

______. “Zhongguo zaoqi gongyehua jieduan yuanshi jilei guocheng de zaihai shi fenxi” (An analysis of the impact of natural disasters on primitive accumulation during the early stages of industrialization in China). Qingshi yanjiu 1 (1999): 62-81.

Xu Zaiping and Xu Ruifang. Qingmo sishinian Shenbao shiliao (Materials on the Shenbao in the last forty years of the Qing). Beijing: Xinhua chubanshe, 1988.

Yang Jianli. “Wan Qing shehui zaihuang jiuzhi gongneng de yanbian: yi ‘Dingwu qihuang’ de liang zhong zhenji fangshi wei li” (Changes in social disaster relief in the Late Qing: Taking the two kinds of relief methods during the “Incredible Famine of 1877-78” as an example). Qingshi yanjiu 4 (2000): 59-76.

Yuanqu wenshi ziliao (Yuanqu literary and historical materials) 4 (1988), compiled by Zhongguo renmin zhengzhi xieshang huiyi Yuanqu xian weiyuanhui (The Yuanqu county committee of the Chinese people’s political consultative conference).

Yuncheng shi bowuguan bian (Yuncheng city museum publication), compiled by Wang Zhangbao. Yuncheng, 1989.

Yuncheng zaiyi lu (Record of disasters in Yuncheng). Compiled and edited by Zhang Bowen and Wang Mancang. Yuncheng: Yuncheng shizi ban, 1986.

Zhang Jie. Shanxi ziran zaihaishi nianbiao, 730 B.C. – 1985 A.D. (A yearly record of Shanxi’s natural disasters). Taiyuan: Shanxi sheng chubanshi, 1988.

Zhang Kemin, ed. “Zhongguo jindai zaihuang yu shehui wending” (Disasters in Modern China and social stability). In Zhongwai lishi wenti ba ren tan (An eight person discussion of questions in Chinese and foreign history), 158-206. Beijing: Guojia jiaowei gaojiao shehui kexue fazhan yanjiu zhongxin, 1998.

Zhao Lianyue. “Renhuo jiazhong le tianzai: 1876-1879 nian ‘Dingwu qihuang’ bianxi” (Man-made disaster adds to natural disaster: critical analysis of the 1876-1879 “Incredible Famine”). Guangxi Youjiang minzu shifan gaodeng zhuanke xuexiao xuebao 12.1 (1999): 41-43.

Zhao Shiyuan. “’Dingwu qihuang’ shulue” (An account of the “Incredible Famine of 1877-78). Xueshu yuekan 141.2 (1981): 65-68.

Zheng Guosheng. “Yipian beiwen” (One stele inscription). Zhongguo qingnian 5 (1961): 33-34.

Zhu Hu. Difangxing liudong ji qi chaoyue: wan Qing yizhen yu jindai Zhongguo de xinchen daixie (The fluidity and transcendence of localism: Late-Qing charitable relief and the supersession of the old by the new in modern China). Beijing: Zhongguo renmin daxue chubanshe, 2006.