Starting in summer 1919, a rainless twelve months visited five Chinese provinces, precipitating China’s most severe food crisis since the 1870s. The famine would affect roughly the same geographical area as in the great North China famine of 1876-79, menacing anywhere between 20 and 30 million destitute residents of Zhili, Henan, Shandong, Shanxi and Shaanxi over the winter of 1920-21. Although the crisis struck toward the beginning of China’s so-called Warlord period, a formidable relief response was mobilised by Chinese society starting in the summer of 1920. Together with a major international relief operation launched later in the year, famine-related deaths were limited to an estimated 500,000 by the time healthy spring harvests returned to much of the North in 1921.

CAUSATION

The immediate catalyst for the famine was partial or total failure of the Autumn 1920 harvest in more than 300 counties, but other underlying factors allowed the drought to lead to starvation conditions for many millions: among these were extreme poverty in remote and densely populated rural areas, limited transport infrastructure, a weak and cash-poor central government, and an ecologically scarred, flood-prone landscape that limited fall-back sources of income for afflicted communities. The failure of harvests across the North in 1920 also came in the immediate wake of the Zhili-Anhui war that July, which saw the troops of three political factions involved in fighting in the environs of Beijing. While it lasted, the fighting disrupted supply routes across the North, destroyed crops, and led to looting in a dozen counties just south of Beijing; short-lived and confined to a handful of counties in the vicinity of Beijing, however, the ten-day war offers little explanation for the food crisis affecting tens of millions in five northern provinces.

A map from a Shanghai newspaper comparing the extent of the five-province North China drought-famine (indicated by horizontal lines covering the entirety of the affected provinces, not merely the stricken areas) with areas ravaged by soldiers (bingzai) in central and south China (Sichuan, Hunan and Guangdong indicated by vertical lines) and floods along the eastern coast in Zhejiang.

Source: Shenbao (Shanghai), October 10, 1920.

High levels of productivity allowed communities on the dry and temperate North China plain to sustain one of the densest populations in all of China, reaching 2,000 people per square mile in the village districts of Zhili (called Hebei from 1928) and more than 3,000 in Shandong.[1] The intense organic fertilization, shallow cultivation, and other inherited farming techniques used by North China’s wheat and sorghum-cultivating communities to achieve this level of productivity was admired at the time by US Department of Agriculture soil management specialists.[2] Yet, North China relies on summer monsoons for the vast majority of its rainfall; when these failed to come, or fell at the wrong time, the one or two harvests a year on which much of the northern population subsisted could be ruined.[3]

Starting in the summer of 1919, drought conditions persisted for a year, most severely in the section of the North China plain north of the Yellow River: central and southern Zhili, western Shandong, and northern Henan. While well-irrigation was generally widespread in the drought-affected regions in 1919, it was used for only a small portion of overall cultivated crops, which were predominantly dependent on rainfall.[4]

Human transformation of the landscape over the centuries had also lowered the terrain’s ability to retain moisture while precipitating frequent flooding. The North China plain had been thoroughly denuded of trees, losing the retention of moisture that root systems provided. Meanwhile, deforestation of slopes along the river system deeper in China’s interior had led to erosion, the build-up of sediment downstream and nearly annual flooding along great stretches of the North China plain. Household reserves and community granaries had also not yet recovered from the disastrous 1917 floods that had struck much of Zhili province just two years before.[5]

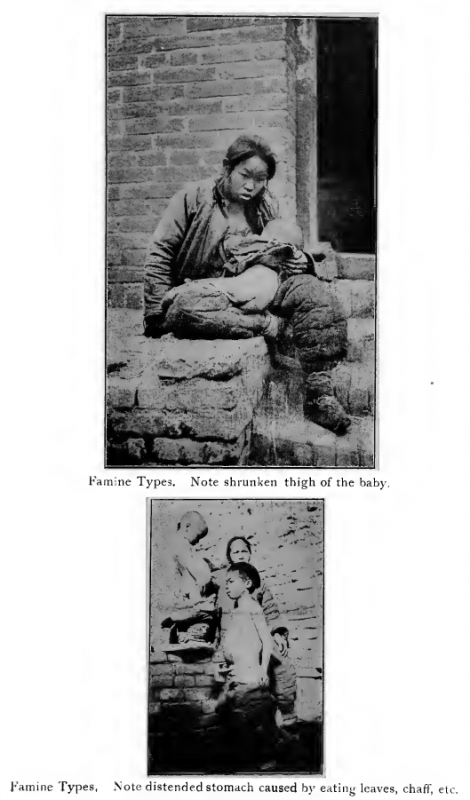

“Disaster stricken (zaimin)” in Tongguan, Shaanxi, near the Henan border.

Source: Jiuzai zhoukan (Beijing), March 20, 1921.

In normal years households in Zhili devoted roughly three-quarters of expenditure on food, rendering them especially vulnerable to even the slightest increase in prices.[6] With limited access to credit in northern villages,[7] few fall-back sources of income for many when harvests failed, and immense local pressure on the food supply by dense populations, enormous amounts of grain imports were required to stabilise and make prices more accessible to the poorest.

Based on the prevailing definition of the “affected population” as defined by the main international relief committee operating through the crisis – in other words, those requiring assistance to survive to the next anticipated harvest in Spring 1921 – the famine struck 20 million people across five provinces; of these, 8,836,772, or nearly half, were in Zhili, where thirteen counties saw over 90 percent of the population in need of assistance. The Chinese government arrived at a considerably higher estimate of 30 million famine-stricken (zaimin).[8]

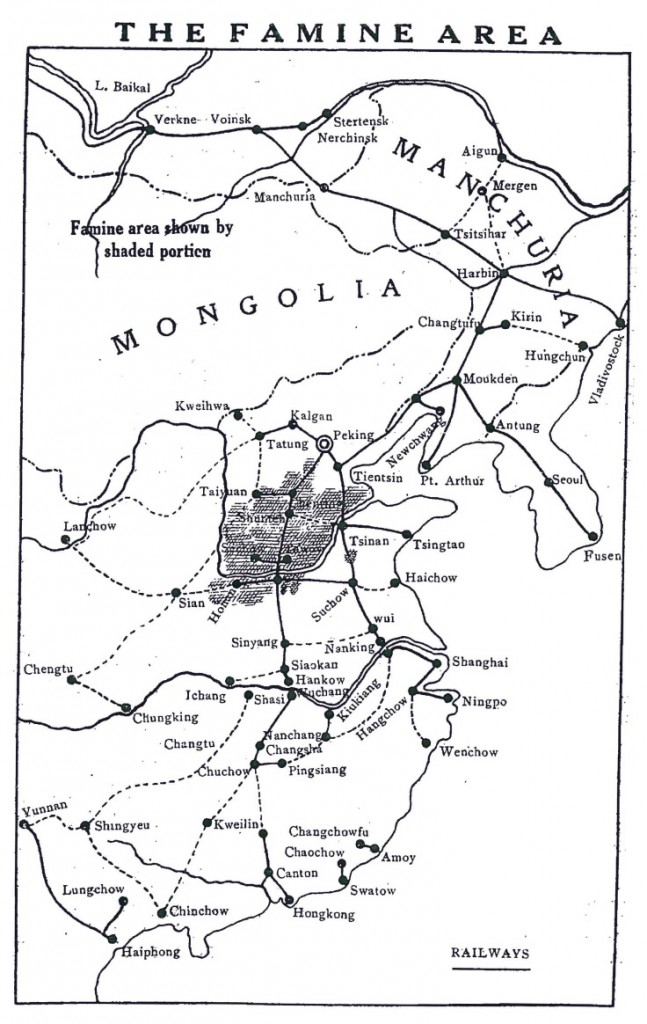

American Red Cross map showing the extent of the drought-famine of 1920-21

in relation to railways (indicated by bold lines) and major cities.

Source: American Red Cross, Report of the China Famine Relief October, 1920 – September, 1921. Courtesy of the Cornell University Library.

RESPONSES

In 1920-21, major efforts to combat the food shortage lasted roughly ten months from September to May and were remarkably decentralised and diverse. They involved a broad-based response by stricken communities, local and regional governments, specially-formed relief societies, and the international community. Efforts pulled from an eclectic combination of methods inherited from disaster relief during China’s late imperial period together with modern communication, publicity and finance, such as trains and newspapers. The famine, in other words, reflected a precise moment in a period of great social and political flux in China: while the state had by 1920 splintered into regional factions with autonomous armies, the country was still a few years away from its descent into a quarter century of incessant civil and anti-Japanese war lasting from 1925 to 1950. In 1920, the political scene was marked by sufficient coordination between rival military governments for massive transfers of resources and refugees into and out of the North China famine field.[9]

When harvest failure loomed in rural communities, many – starting with able-bodied men – left along well-established seasonal migration routes to Manchuria or south to Hankou or Shanghai; those that stayed behind turned to fallback measures, which for some involved growing peanuts and other hardy crops in marginal lands along river beds; others, especially in the highly-alkaline flood plains of the Yellow River, weathered the 1920-21 food crisis by producing earth salt for the market, whose home production had traditionally been a major source of income for struggling families.[10]

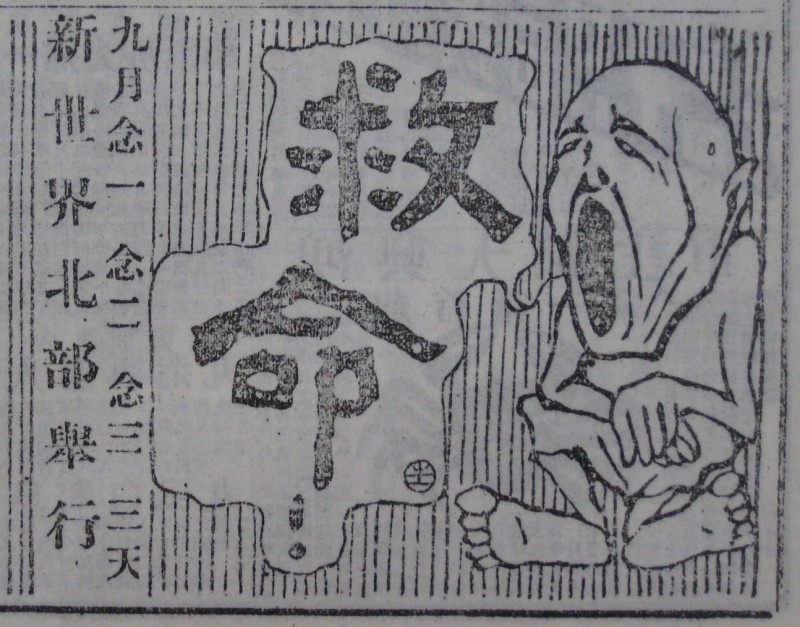

An advertisement stating ‘Save life!’ for a three-day disaster relief event

at Shanghai’s New World entertainment complex.

Source: Shenbao (Shanghai) October 31, 1920.

Official acts to combat rising grain prices included the remission of taxes on the production and transport of grain by the central state and bans on the distilling of alcohol in greater Beijing to take pressure off the food supply, policies that were continued into the Spring of 1921.[11] While relief agencies of the central and provincial governments would carry on moderate amounts of relief distribution over the year, the main official role over the crisis was coordinating relief at the district level while facilitating the movement of resources nationwide (the Ministry of Communications remitted eight million yuan in railway transport fees for relief grain moving on the national rail system over the year).[12]

Starting in late summer 1920, widespread scavenging for roots and herbs, or preparation of ‘famine foods’ meant to stave off hunger, such as tree bark, sorghum husks, and Fuller’s earth, indicated the exhaustion of household cash or grain reserves and the arrival of full-fledged famine conditions. Some communities were abandoned temporarily in part or whole, with entire families fleeing the drought zone. Other communities conducted meetings at which mutual aid plans were devised at village level, involving the establishment of soup kitchens or distribution of money, grain and clothing as either loans or outright grants depending on the level of destitution of the recipients.[13]

At the district level, when local granary stores were exhausted, merchants and gentry pooled funds to import grain from neighboring provinces in a bid to stabilise local grain prices (pingtiao) through discounted sales to the poor, a coordinated response to local food scarcity practiced in China for centuries.[14] When many families could no longer afford even discounted grain, some communities opened soup kitchens starting in mid-Autumn 1920 serving several hundred to several thousand at each, and as many as 25,000 people a day in the case of one gentry-run station in Anyang, Henan.[15]

News reel clip of a famine aid parade in Shanghai in Spring 1921.

Source: British Pathé/Pathé Gazette, ‘Natives of Shanghai,’ newsreel, May 23, 1921

As local resources ran out, considerable volumes of grain were brought to maintain these operations. Over the month of December 1920, Chinese official and charity relief groups moved 170,457,191 jin of grain along the national rail network, mostly from Manchuria, into the five-province famine zone, which amounted to daily relief rations for 31 days for roughly 8.8 million people.[16] As the winter wore on, Manchurian grain transported into North China increased, exceeding in January 1921 by more than six-fold the previous record set in 1919.[17]

Apart from that originating with county governments and official military and other relief agencies, much of the movement of aid into the famine zone was mobilised by several dozen Chinese relief societies that formed in Beijing, Tianjin, and other cities in late summer and autumn 1920.[18] In October, some of these Chinese societies combined with efforts initiated by members of the resident foreign community to form eight joint Chinese-foreign ‘international’ relief societies with operations in the five province-famine field. After getting off the ground in January 1921, the international societies assisted, largely with grain hand-outs, roughly seven million people, the majority of them in April and May just before the Spring harvest. In addition, the American Red Cross assisted labourers and their dependents, a total of 928,000 people, through the famine through work relief projects, centred in Shandong. Finally, Christian missions spent at least two million Chinese yuan on relief over the year.[19]

By the time of the Spring harvest in early June an estimated 500,000 had died across the five provinces, mainly due to malnourishment and exposure to the cold; famine-related disease, typhus in particular, was kept relatively low through epidemic prevention measures, largely by the international societies, which credited delousing and a policy of keeping relieved populations scattered and close to their homes.[20] While horrific, half a million deaths – or 1.6 to 2.5 percent of the famine-afflicted – was a considerably lower death rate than the 9.5 to 13 million of the 1870s famine, or the several million later dying in the next major famine to strike the North in the late 1920s. Tellingly, incidents of cannibalism do not crop up in accounts of 1920-21, unlike some other major famines of China’s modern period.

The cover of the North China Relief Society’s Jiuzai zhoukan (Famine Relief Weekly),

one of several periodicals devoted to drought-famine relief matters over the course of 1920-21.

Source: Jiuzai zhoukan (Beijing), April 24, 1921.

CONSEQUENCES

The drought and ensuing famine of 1920-21 occurred in a moment of great intellectual and political ferment in China, between the launching of the May Fourth movement in 1919 and the inaugural meeting of the Chinese Communist Party in July 1921. While it spurred major efforts to engineer famine prevention infrastructure and credit cooperatives in China’s interior through the creation of the China International Famine Relief Commission, the famine – along with other major humanitarian crises that followed in the 1920s – would ultimately contribute to the general social malaise fuelling the revolutions in the ensuing decades.

Back-to-back harvest failures followed by increasingly desperate measures to pull families through ten months of extreme scarcity led to further immiseration of communities already living already on thin margins of existence. Families disintegrated amid famine by flight, by suicide, and by the sale of children and teenagers, mainly girls, often to join more affluent families as servants, concubines or future wives, but also to traffickers for the sex and entertainment industry.

A man dismantling his house for sale during the famine.

Source: American Red Cross, Report of the China Famine Relief October, 1920 – September, 1921. Courtesy of the Cornell University Library.

North China was predominantly an owner-cultivator economy, with some three-quarters of all northern farmers owning their land. A considerable amount of land changed hands during the crisis, but it is unclear how much: in one south Zhili district with 40 percent of the population rendered destitute by the famine, 13 percent of all land owned before the crisis was sold, which may or may not be representative. There was in fact a steady rise in land values across the region in the period, which does not suggest land sales en masse, and which stands in marked contrast to the precipitous drop in land values later in the decade in Gansu and Shaanxi when those northwestern provinces were hit by severe famine in 1928-30.[21]

Chinese farming families were more likely to choose deep debt over alienation from their land, and so many families survived the crisis by becoming indebted to more affluent neighbors; homes were often devoid of roofs or furniture by the end of the crisis, having been stripped bare for sale at the peak of food prices. Productive capital, such as farm tools and livestock, were readily sold off and therefore unavailable when planting resumed. Families commonly lost winter garments, which many had pawned in summer 1920 to purchase seeds for the planting of winter wheat, making them especially vulnerable in the coming winter.[22]

Fleeing by cart in an unspecified section of the drought-famine zone.

Source: Jiuzai zhoukan (Beijing), May 8, 1921.

As famines had in the past, the food crisis also changed China’s demographic landscape. As their forebears had done, one million fled the North China plain for the three northeastern provinces comprising what was then known as Manchuria: Fengtian, Jilin and Heilongjiang; roughly one third stayed and settled there.[23] Many of these refugees fled the disaster zone for free, subsidized by the Chinese state-owned railroad, along the 6,000 miles of track that had been laid in China since the great 1870s famine.[24] Still, only one rail line cut through the heart of the 1920-21 famine zone, and relief, as well as refugee movement, was still conveyed as it had been for centuries in the majority of drought districts, by foot or cart over notoriously slow-going, rutted roads. These infrastructural failings spurred calls for increased investment in famine prevention across the country.

In autumn of 1921 representatives of the eight joint Chinese-foreign relief committees formed the China International Famine Relief Commission with leftover funds from the 1920-21 relief operation. The Commission, based in Beijing and with a one-man majority of foreign committee members to maintain its independence from Chinese government, would serve through the 1920s as one of the largest sponsors in China of road building, dike repair and other engineering projects aimed at famine prevention.[25]

The famine unfolded four years into a period, later dubbed the Warlord period (1916-27), of increasingly intense civil war between rival military cliques in the disintegrating Chinese Republic after the death of President Yuan Shikai in 1916. The fighting between provincial armies that began in Hunan in late 1917 soon spilled over into neighbouring provinces, at first mostly in central and south China;[26] by the mid-1920s nearly all of China had become a theater of disastrous droughts and floods exacerbated by banditry and nearly incessant war, leading 1920-21 American relief worker Walter Mallory to famously dub the country a “Land of Famine” in 1926.[27]

HISTORIOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW

Few historians have written on the 1920-21 North China famine. Massive in scale, the famine was nonetheless upstaged in two important ways. First, it occurred amid a surge of global relief activity in the wake of the First World War, led by Herbert Hoover’s American Relief Administration in Europe, the Near East, and Russia. This surge in international relief mobilisation in the late 1910s and early 1920s is the focus of a recent flurry of studies: Keith David Watenpaugh, Bread from Stones: the Middle East and the making of modern humanitarianism (Oakland, 2015); Bruno Cabanes, The Great War and the Origins of Humanitarianism, 1918-1924 (Cambridge, 2014); and Bertrand Patenaude, The big show in Bololand: the American relief expedition to Soviet Russia in the famine of 1921 (Stanford, 2002). But 1920-21 China is beyond the scope of these studies. Major histories of relief organisations that were active in China also overlook the event: Julia Irwin’s Making the world safe: the American Red Cross and a nation’s humanitarian awakening (Oxford, 2013), for example, does not mention the organisation’s role in 1920-21 China.

Another reason for the later obscurity of what was an enormous humanitarian crisis is that it occurred during China’s so-called Warlord era (1916-27). This chaotic period of increasing civil warfare between the fall of the Qing Dynasty and rise of the Nationalists in 1928 has attracted considerably less attention from historians of disaster than, say, the Second Sino-Japanese war or the Great Leap Forward famine under Mao in the 1950s, both of which have recently seen a growth in academic studies. That said, over the century since 1920 a few important works have at least touched on the 1920-21 famine, namely Walter Mallory, China: Land of Famine (New York, 1926); Andrew Nathan, A History of the China International Famine Relief Commission (Cambridge, Mass., 1966); Marie-Claire Bergère, “Une crise de subsistence en Chine, 1920-1922.” Annales: Economies, Societés, Civilisations (1973); Xia Mingfang, et al., 20 shiji Zhongguo zaibian tushi (Fuzhou, 2001); and Lillian Li, Fighting Famine in North China: State, Market, and Environmental Decline, 1690s-1990s (Stanford, 2007). Based largely on foreign sources on the 1920-21 famine, however, these histories stress the international relief efforts mobilised halfway through the crisis in the spring of 1921. They are largely silent on relief responses mobilised earlier by Chinese state and society over the autumn of 1920, including local relief and disaster management by Chinese military authorities. Unfortunately, the social and political dynamics as they played out on the drought-stricken North China plain in 1920-21 are still little appreciated. Despite the relatively successful ways in which military authorities, local elites, and international actors coordinated relief for tens of millions over the year, the event has come to serve merely as part of the overall backdrop of civil strife and mass suffering during China’s Warlord era.

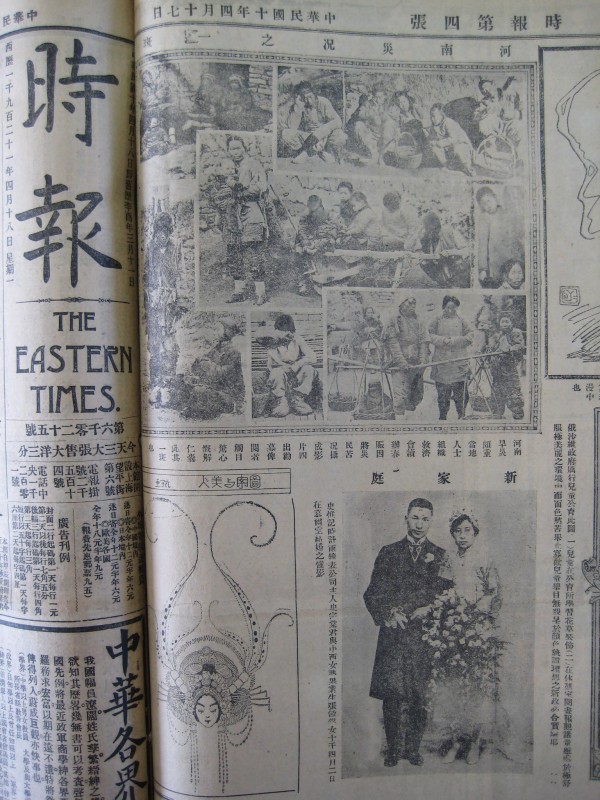

Disaster victims in Henan Province presented in a Shanghai newspaper

near the height of the famine.

Source: Shibao (Shanghai), April 17, 1921.

TYPES OF SOURCES

The most comprehensive and easily accessible sources are reports issued by the major international relief organisations, such as the American Red Cross’s Report of the China Famine Relief October, 1920 – September, 1921 and Peking United International Famine Relief Committee’s The North China Famine of 1920-1921, with Special Reference to the West Chihli Area, published in both Chinese and English versions Beijing in 1922. (Both reports are available in major university libraries in, for example, the United Kingdom and United States, and digital copies exist online of the Yale and Cornell copies.) As valuable as these reports are, they cannot come close to capturing all the relief activity over the year. The North China Famine report puts relief totals over the year from all sources at $37 million when at the famine’s outset the authors themselves had estimated relief needs would be $120 million.[28] The report then concedes that its estimate for Chinese relief societies is “merely a guess”.[29] Considerable relief efforts, both formal and informal, by native groups and individuals are clearly left out of these reports.

Good sources for the activity of Chinese relief groups are the periodicals devoted to covering the disaster that year, such as the weekly Jiuzai zhoukan and daily Zhenzai ribao, both published in Beijing. Provincial gazettes such as the central government’s Zhengfu gongbao, and Laifu bao issued by the Shanxi provincial government in Taiyuan, regularly covered official relief contributions and policies. National news dailies also gave extensive daily coverage of the crisis, especially Beijing’s Chenbao, the Tianjin-based and government-owned Da gongbao, and the Japanese-owned and Beijing-based Shuntian shibao. A handful of news dailies in Beijing at the time, most notably Xiao gongbao and Shihua, offer great detail on the disaster experience at street level in and around the capital. Lastly, local gazetteers (difang zhi), and especially their biographical sections and transcriptions of stone stele and grave inscriptions, are the best window onto the disaster experience in the afflicted rural communities themselves.

Pierre Fuller is Lecturer in East Asian History at the University of Manchester

NOTES

[1] Mallory, China Land of Famine, 15-7.

[2] See King, Farmers of Forty Centuries.

[3] Buck, Land Utilization in China, 108-29.

[4] Buck, Land Utilization in China, 187; King, Farmers of Forty Centuries, 223; Jiuzai zhoukan, December 12, 1920.

[5] Li, Fighting Famine in North China, 285-95.

[6] Dittmer, ‘An Estimate of the Standard of Living in China’, 116. Dittmer’s study used statistics gathered in the rural outskirts of Beijing.

[7] Buck, Land Utilization, 465.

[8] Edwards, North China Famine, 10-11; Xia, Minguo shiqi ziran zaihai, 385.

[9] Fuller, “North China Famine Revisited”, 820-50.

[10] Thaxton, Salt of the Earth, 115, 249-50.

[11] Shuntian shibao (Beijing), September 23, 1920; Shihua (Beijing), February 4, 1921; Da gongbao (Tianjin), December 27, 1920; Fengsheng (Beijing), April 14, 1921.

[12] Zhongguo minbao (Beijing), November 4, 1920; Edwards, North China Famine, 21.

[13] Laifu bao (Taiyuan), October 10, 1920; Wei xianzhi 1929 16:46a.

[14] Shuntian shibao (Beijing), October 9, 1920; Celestial Empire (Shanghai), November 27, 1920.

[15] Shuntian shibao (Beijing), January 1, 1921; Edwards, North China Famine, 83.

[16] Zhengfu gongbao (Beijing), June 13, 1921.This estimate is calculated using the famine ration of five-eighths of a jin, or 1,400 calories, per day per idle woman or teenager, who formed a majority of relief recipients, a ration stipulated by the Chinese Ministry of Interior for soup kitchen operations and also employed by the American Red Cross. Fuller, “North China Famine Revisited”, 839; American Red Cross, Report of the China Famine Relief, 18.

[17] North China Herald (Shanghai), March 5, 1921.

[18] Egan, ‘Fighting the Chinese Famine’, April 9, 1921.

[19] American Red Cross, Report of the China Famine Relief, 228; Edwards, North China Famine, 3, 20, 25.

[20] Edwards, North China Famine, 78-84.

[21] Buck, Land Utilization in China, 196, 332; Edwards, North China Famine, 15.

[22] Edwards, North China Famine, 14-5.

[23] Yuandong bao (Harbin), December 30, 1920; Ma Ping’an, Jindai Dongbei yimin yanjiu, Jinan, 2009, 46.

[24] Mallory, Land of Famine, 30.

[25] Nathan, A History of the China International Famine Relief Commission, Cambridge, Mass., 1965, 11.

[26] McCord, Power of the Gun, 253-64.

[27] Mallory, China Land of Famine.

[28] The figures are in Mexican silver dollars, a common currency among many used in 1920s China. Fuller, “North China Famine Revisited”, 824-25.

[29] Edwards, North China Famine, 25.

PRIMARY SOURCE BIBLIOGRAPHY

Celestial Empire (Shanghai)

Da gongbao 大公報 (Tianjin)

Fengsheng 峰聲 (Beijing)

Jiuzai zhoukan 救災周刊 (Beijing)

Laifu bao 来复報 (Taiyuan)

North China Herald (Shanghai)

Shibao 時報 (Shanghai)

Shihua 實話 (Beijing)

Shuntian shibao 順天時報 (Beijing)

Zhenzai ribao 賑災日報 (Beijing)

Zhengfu gongbao 政府公報 (Beijing)

Zhongguo minbao 中國民報 (Beijing)

Yuandong bao 遠東報 (Harbin)

Wei xianzhi 威县志 1929

American Red Cross. “Report of the China Famine Relief, American Red Cross, October 1920 – September, 1921.” Shanghai, 1921?

Augustana Synod Missionaries. Our Second Decade in China, 1915-1925: Sketches and Reminiscences by Missionaries of the Augustana Synod Mission in the Province of Honan. Minneapolis: Board of Foreign Missions, 1925.

Buck, John Lossing. Land Utilization in China. London: Oxford University Press, 1937.

Dittmer, C. G., “An Estimate of the Standard of Living in China,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 33/1 (Nov., 1918), 107-126.

Edwards, Dwight W., ed. The North China Famine of 1920-21, with Special Reference to the West Chihli Area being the Report of the Peking United International Famine Relief Committee. Taipei: Ch’eng Wen Publishing Company, 1971. (First printed in Beijing, 1922.)

Egan, Eleanor Franklin. “Fighting the Chinese Famine,” The Saturday Evening Post, 9 April 1921.

Fuller, Stuart and M. T. Liang, eds. “Statement of Aims and Report on Famine Conditions and How They Are Being Met with Map of the Famine Region.” Tianjin: Tientsin Press for the North China International Society for Famine Relief cooperating with the Chinese-Foreign Relief Committee, Shanghai, 1920.

King, F. H. Farmers of Forty Centuries or Permanent Agriculture in China, Korea and Japan. Madison, Wisc., 1911.

MacNair, Harley Farnsworth. With the White Cross in China: the Journal of a Famine Relief Worker with a Preliminary Essay by Way of Introduction. Peking: Henri Vetch, 1939.

Mallory, Walter. China: Land of Famine. New York: American Geographical Society, 1926.

Pathé Gazette, ‘Natives of Shanghai,’ newsreel, May 23, 1921

SECONDARY SOURCE BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bergère, Marie-Claire. “Une crise de subsistence en Chine, 1920-1922.” Annales: Economies, Societés, Civilisations 28, no. 6 (Nov.-Dec. 1973) 1361-1402.

Fuller, Pierre. “North China Famine Revisited: Unsung Native Relief in the Warlord Era, 1920-21,” Modern Asian Studies 47/3 (May 2013).

Fuller, Pierre. “‘Barren Soil, Fertile Minds’: Drought Famine & Visions of the ‘Callous Chinese’ circa 1920,” The International History Review 33/3 (September 2011).

Li, Lillian. Fighting Famine in North China: State, Market, and Environmental Decline, 1690s-1990s. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

Li, Wenhai, Xia Mingfang, et al. Zhongguo jindai shi da zaihuang (The Ten Greatest Natural Disasters of Modern China). Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1994.

Ma Ping’an, Jindai Dongbei yimin yanjiu. Jinan: Qilu shushe, 2009.

McCord, Edward. The Power of the Gun: the Emergence of Modern Chinese Warlordism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Nathan, Andrew. A History of the China International Famine Relief Commission. Cambridge, Mass.: East Asia Research Center, Harvard University Press, 1966.

Ren, Yunlan. Jindai Tianjin de cishan yu shehui jiuji (Charity and social relief in modern Tianjin). Tianjin: Tianjin renmin chuban she, 2007.

Su, Xinliu. Minguo shiqi Henan shui han zaihai yu xiangcun shehui (Rural Henan society amid flood and drought disasters during the Republican era). Zhengzhou: Huanghe shuili

chuban she, 2004.

Thaxton, Ralph. Jr. Salt of the Earth: The Political Origins of Peasant Protest and Communist Revolution in China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Xia Mingfang, Minguo shiqi ziran zaihai yu xiangcun shehui (Natural disasters and rural society in the Republican era). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2000.

Xia Mingfang, and Kang Peizhu, eds., 20 shiji Zhongguo zaibian tushi (A history of natural disasters in twentieth century China). Fuzhou: Fujian jiayu chuban she, 2001.