The earthquake that hit China’s remote Gansu Province in late 1920 was the world’s second deadliest of the twentieth century. It struck in the evening of the 16th of December in the rural district of Haiyuan near Inner Mongolia, leading to the deaths of more than 200,000 people and to severe destruction over an area of 20,000 square kilometers. Occurring in the early years of escalating civil war in the Chinese Republic, the disaster was overshadowed by major political and humanitarian crises elsewhere in the country that year, and remains a remarkably little known event despite the scale of its destructive powers and human toll.

CAUSATION

Generally known today as the Haiyuan earthquake, the quake’s epicenter was beneath the outskirts of Haiyuan in eastern Gansu, a region that in today’s People’s Republic forms part of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. Situated along a stretch of the Yellow River south of the Gobi desert, the area around Haiyuan is part of the most extensive stretch of loess terrain on Earth.[1] Cave dwellings dug out of loess, a sediment of fine yellow soil in places hundreds of meters deep, were the predominant form of home construction in this section of northwest China, but were also particularly susceptible to collapse under seismic activity.

The ruins of a temple in the county seat of Jingning County, Gansu, in early 1921.

Source: Jingning County Archives

The initial quake struck with a maximum destructive intensity of XII on the Mercalli scale, causing 675 major loess landslides in the region;[2] estimates of the strength of the energy released by the tremor range from a magnitude of 7.8 (according to the US Geological Survey) to 8.5 (according to the Chinese Earthquake Administration).[3] Witnesses noted that buildings in the nearby provincial capital of Lanzhou were surprisingly resilient under the stress of the quake and the ensuing months of aftershocks, while the vast majority of destruction occurred in rural areas abutting the epicenter that consisted largely of cave dwelling communities, such as Haiyuan and Guyuan especially.[4]

Based on county reports from 50 (and in some cases 53) counties, the estimates of total human deaths due to the earthquake ranged from 234,117 to 314,092.[5] Many of the dead – possibly a majority – were among the region’s Chinese Hui Muslim population, which lost the most prominent Islamic figure in China at the time, Sufi sect leader Ma Yuanzhang, who was at prayer when the quake hit in the predominantly Muslim valleys of Longde district where a third of the population was killed.

One estimate put total property losses in Gansu at 30 million yuan (roughly US$20 million at the time).[6] Much of this loss was in the form of destroyed dwellings and granary stocks; in 14 counties, over 70 percent of structures collapsed.[7] Livestock were another important form of wealth lost in the disaster, although tallies of sheep, cattle and other farm animals crushed to death varied widely, ranging from 808,270 to 1.7 million head.[8]

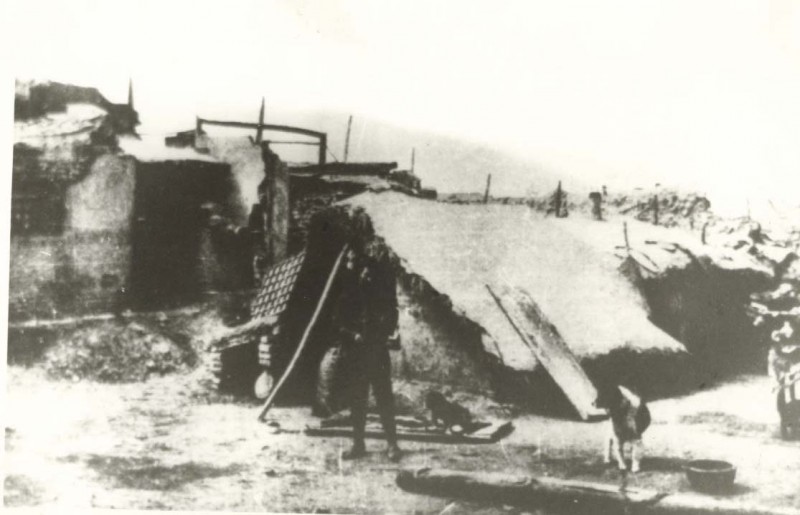

A man stands in front of his temporary shelter in the town of Jingning, Gansu, in early 1921.

Source: Jingning County Archives

RESPONSES

The destruction of homes and granaries beneath collapsed hills subjected the initial survivors both to hunger and to exposure to the windstorms and snowfall that immediately followed the quake. Vulnerable to bandit activity, many thousands roamed in a deformed landscape that was stripped of its roads, and devoid of standing structures and familiar natural landmarks. Post-quake investigations unfortunately do not make it clear what portion of total fatalities may have been due to ground-shaking versus landslides, or to starvation or exposure in the quake’s aftermath, a subject that requires further research.[9]

Soldiers and officers operating out of the regional garrisons commanded by General Ma Fuxiang, in Ningxia, and General Lu Hongtao, in Pingliang, provided the first intelligence on the disaster, and also served as first responders, distributing tents and emergency provisions to communities in some of the most hard-hit areas. In some districts, local gentry and merchant associations set up soup kitchens and contributed emergency aid, while in others magistrates issued tents and grain to the public from official granaries.[10]

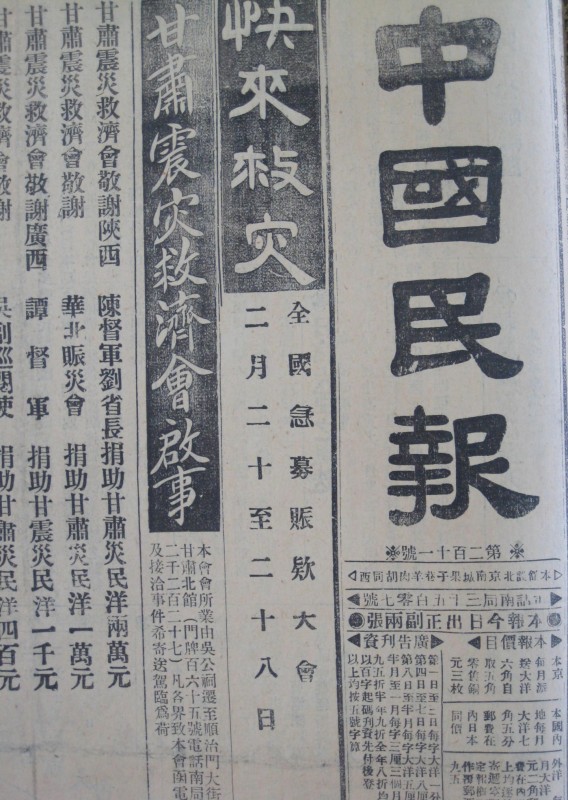

Gansu relief announcements on the front page of the Beijing daily Zhongguo minbao, 28 February 1921

Source: photograph by the author

Modest amounts of relief monies and materials were raised and dispatched to the region by provincial and county governments elsewhere in China, by fundraising groups formed by Gansu natives sojourning in Beijing, Shanghai and elsewhere in China and overseas, by charities in provinces such as Hunan and Jilin, and from the central government’s relief bureau in Beijing.[11] Later in winter, foreign missionaries in Gansu joined efforts to reconstruct communities, re-open communication lines and transport routes, and unblock the river systems before the snowmelt of spring threatened mass flooding.[12]

The catastrophe that hit Gansu in late 1920 and early 1921 struck just as a drought famine affecting 20-30 million people on the North China plain was reaching a climax and absorbing the limited attention and relief capacities of the Chinese state and general public; the resources generated for the relief and reconstruction of Gansu in 1921 was undoubtedly a tiny fraction of the enormous losses inflicted on its people by the earthquake.

SOURCES

County and provincial archives in northwest China are surprisingly lacking in materials on the Haiyuan earthquake of 1920. The local histories, scattered news reports, compilations of seismic data, and missionary writings used for this article give a sense of the limited types of primary sources that exist for this event.

Pierre Fuller is Lecturer in East Asian History at the University of Manchester

NOTES

[1] He Xiubin, Keli Tang, and Xinbao Zhang, “Soil Erosion Dynamics on the Chinese Loess Plateau in the Last 10,000 Years,” Mountain Research and Development 24/4 (2004), 342–3.

[2] Li Tianchi, “Landslide Disasters and Human Responses in China,” Mountain Research and Development 14/4 (1994), 342.

[3] Guojia dizhen ju Lanzhou dizhen yanjiusuo, ed., Yijiuerling nian Haiyuan da dizhen (1980), 1. http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/world/events/1920_12_16.php

[4] Ebenezer J. Mann, “The Earthquake,” Links with China and Other Lands 31 (April 1921), 331 (MS380302, SOAS Library, University of London).

[5] Zhongguo minbao (Beijing), 1-5 March 1921. Jiuzai zhoukan (Beijing), 13 March 1921. Xinlong zazhi (Beijing), 20 April 1921. Xie Jiarong, Minguo jiu nian shier yue Gansu dizhen baogao, republished in Gansu sheng dizhen ziliao huibian, ed. Guojia dizhen ju Lanzhou dizhen yanjiu suo (Lanzhou, 1989), 277–350.

[6] Zhongguo minbao (Beijing), 26 Feb. 1921.

[7] Zhongguo minbao, 1-5 March 1921.

[8] Jiuzai zhoukan, 13 March 1921. Xinlong zazhi, 20 April 1921.

[9] Upton Close and Elsie McCormick, “When the Mountains Walked: an account of the most recent earthquake in Kansu Province, China, which destroyed 100,000 lives,” National Geographic Magazine 41/5 (May 1922), 445–64.

[10] Aiguo baihua bao (Beijing), 25 Dec. 1920. North China Herald (Shanghai), 15 Jan. 1921. Minguo Guyuan xianzhi vol. 1 (Yinchuan, 1992), 689, 692.

[11] Xinren zhenzai ji, (Gansu Provincial Library).

[12] Wang Lie, Diaocha Gansu dizhen zhi baogao (Gansu Provincial Library). Mrs Howard Taylor, The Call of China’s Great Northwest: Kansu and Beyond (London, c. 1923), 46-57.