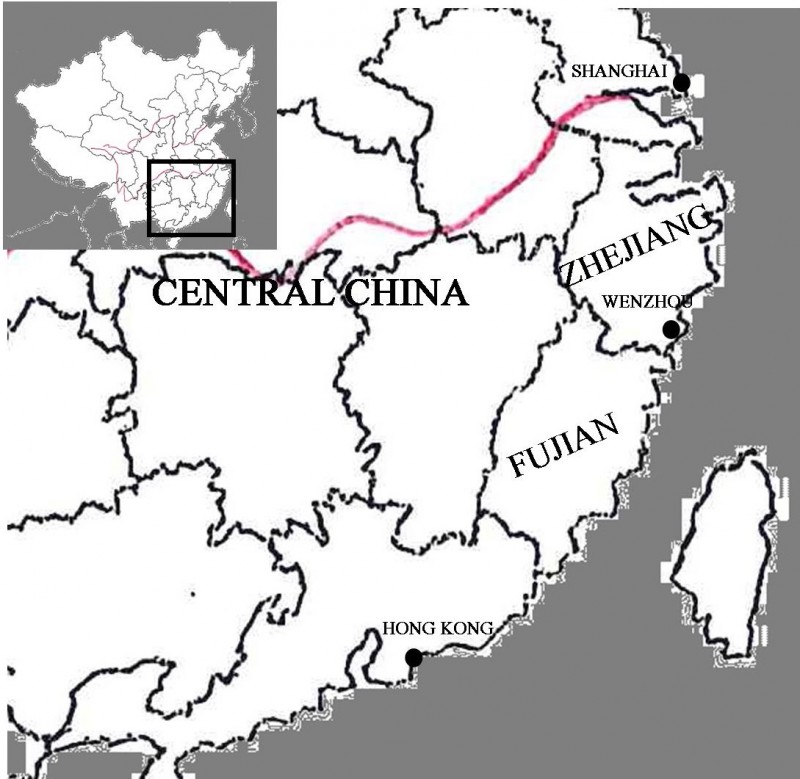

The Zhejiang flood involved the flooding of the Wenzhou River in August 1912, devastating the surrounding area for a number of months. The main effects of the flood were felt in the south of Zhejiang, in Wenzhou and the surrounding areas, including Qingtian and Yunhe.[1] With an estimated total death toll of around 220,000 the flood was described at the time by a newspaper based in nearby Shanghai as “one of the most devastating ever experienced.”[2]

CAUSATION

Numerous factors progressed quickly into a full-fledged disaster, initiated first by typhoon conditions in the Wenzhou region on the 29th of August, “combined with torrential rain and high tides” over a period of 24 hours.[3] This caused a swelling of the upper-most section of the river – which was enclosed by mountains and hills – resulting in an excessive build-up of water, which subsequently poured down into urban areas through large waves, causing huge damage. [4] The suddenness of the flooding was also a key aspect of the disaster, with water rising by “four or five feet” within minutes.[5]

The scale of the flooding was extensive, affecting the Qingtian and Yunhe districts of Zhejiang as well as Wenzhou, where the disaster originated. The event was captured in headlines on several continents, with some papers overseas reporting that around 30,000 had drowned as a result of the flooding of Quzhou and around 10,000 in “Tsingdie,” located around 10 miles from Wenzhou itself and situated at the foot of the hills where the flood began.[6] Another international report suggested the typhoon alone had killed around 40,000 people.[7] Accounts from survivors of the flooding indicate that the town of “Keneo” was “entirely destroyed” resulting in the death of almost its entire population, although no figure from this particular town is known.[8] The districts of Rui’an and Pingyang had also “suffered terribly,” with an estimate total death toll of around 30,000 to 40,000 people.[9] A major Shanghai paper put the total death toll from the flood at 220,000.[10]

In addition to the severe loss of life, there was also huge damage to infrastructure in many parts of southern Zhejiang; not only had buildings been wiped out as many cities and towns were destroyed, but also the affected regions were completely cut off by rail and wire communications, increasing the impact of the disaster.[11] In the months and years following the flooding further fears were expressed of similar disasters occurring in the region, and as a result residents erected ‘inferior’ or temporary housing on higher areas. Reclamation and rebuilding was reportedly conducted largely through primitive means due to a lack of necessary tools, resulting in reliance on hand tools and baskets to rebuild damaged areas.[12] Yet, despite the severity of the damage caused by the flooding in Zhejiang in 1912, optimistic accounts of the lack of damage to crucial rice fields indicate the importance of the crop yield, and agricultural production generally, to the process of recovery in affected communities at the time.[13]

RESPONSES

The immediate response to the flood, which commenced the following day, was largely a collective effort, incorporating the efforts of both officials and civilians.[14] The civilian-led rescue efforts were reportedly spurred in part by offers of reward for each life saved, which, provided by Chinese residents themselves affected by the disaster, resulted in the rescue of around 150 to 200 people.[15] In conjunction with these localised efforts, the official response to the flooding reflected the increasingly decentralized governance of the early Republican period (1912-1928). There was a evident lack of response from any form of centralised governing body, and instead regional officials conducted the rescue efforts and aided with the subsequent recovery. These officials also sought to obtain reliable accounts of the damage and death toll, and much of the subsequent rebuilding projects were funded by grants from the regional government.[16] This was further aided by relief money given by foreign residents to those affected; for example the financial aid provided by the residents of Weihai stood at a total of $1,223.50[17]

Alexander Ankers is a History undergraduate in the class of 2017 at the University of Manchester.

NOTES

[1] ‘The Typhoon at Wenchow: Report from Eye Witnesses.’ The North – China Herald; 21 Sept. 1912.

[2] ‘The Great Typhoon: The City That Was Lost,’ The North China Herald; 14 Sept. 1912.

[3] ’40,000 killed by Typhoon: Chinese Province is Desolated by a Great Storm’ The Enterprise (Williamstown N.C.) 13 Sept. 1912.

[4] North China Herald, 14 Sept 1912. ‘Floods in China: 40,000 drowned,’ The Advertiser (Adelaide) 11 Sept. 1912.

[5] North China Herald, 14 Sept. 1912.

[6] ‘Tens of Thousands Perish by Typhoon, Wind and Tide,’ Chicago Daily Tribune, 10 Sept. 1912; ‘The Wenchow Typhoon,’ The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 Oct. 1912.

[7] ‘40,000 Chinese Drowned: Flood Destroys Towns,’ The Argus (Melbourne), 10 Sept. 1912.

[8] North China Herald, 14 Sept. 1912.

[9] North China Herald, 14 Sept. 1912.

[10] Shenbao, 20 Sept. 1912.

[11] ‘40,000 are Drowned by Typhoon in China’ Chicago Examiner. 10 Sept. 1912.

[12] North China Herald, 25 Apr. 1914.

[13] North China Herald, 14 Sept. 1912.

[14] North China Herald, 14 Sept. 1912.

[15] North China Herald, 14 Sept. 1912.

[16] North China Herald, 25 Apr. 1914.

[17] North China Herald, 7 Dec. 1912.