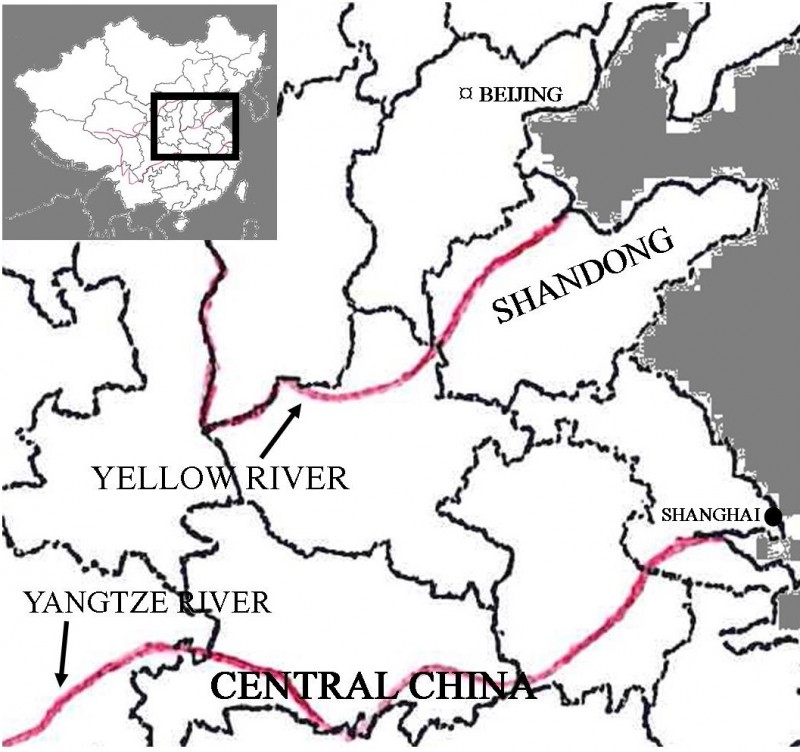

On the 8th of August 1898 the banks of the Yellow River burst through the dyke system at various locations in Shandong province.[1] On the 14th of November, the Qing official Li Hongzhang was sent by the Empress Dowager to devise ways to prevent further flooding, suggesting the crisis had come to a close, but the effects of the flood continued to felt long after this date.[2]

CAUSATION

The river burst its banks in three locations on the south side of the river, and in one place on the north side, affecting 34 counties in Shandong and the neighbouring provinces.[3] The banks burst on the north side first, near the town of Yuzhou in the Tongzhou district, while the first break on the south side, north-east of Jinan, the provincial capital, measured at least 7 miles across.[4] The total death toll of the flood is unknown, but an estimated 2,000 people drowned in Shandong province by the 25th of October, while 100,000 were left homeless in the same area. In addition to the loss of many settlements, the flood also resulted in the destruction of cereal crops and the loss of cattle, precipitating a famine that affected one million people in Shandong province alone.[5] Later on in the spring of 1899, it was estimated that at the very least two million people were affected by the famine.[6] Much of the land was submerged, often in depths reaching 12 feet, while 9 districts in range of the break at Jinan were totally inundated.[7]

The meteorological cause of the flood was heavy rains throughout the summer, and the flooding was prolonged and worsened by other events such as a freak storm beginning on the 9th of September, which caused four days of constant heavy downpour.[8] The extent of death and destruction was also worsened by socio-economic problems, such as the poor structure of the homes of many rural peasant farmers, although rich and poor people alike were affected. Geographically, Shandong province lies on the North China Plain, which is flat and constitutes a large part of the Yellow River floodplain – the topography of the region made it especially vulnerable to flooding. The large majority of crops were grown on the fertile alluvial soils of the floodplain without protection or channelling, accounting for the huge loss of crops in the flooding, and the subsequent famine. There were additional political causes – German residents, keen to gain concessions of land in the province, pressured the Qing government to dismiss anti-foreign officials there. It was the conservative-minded officials concerned with traditional matters of state, such as Shandong Governor Li Bengheng, who had been so effective in maintaining dykes and preventing floods of the Yellow River beforehand, who were targeted, leaving authorities less familiar with the water control system to unsuccessfully manage flood threats.[9]

While the floods were occurring in Shandong, the rest of China was experiencing a political crisis in the form of the failed ‘100 days reform’ movement. This resulted in a coup d’etat of the Guangxu Emperor, the movement’s leader, by Empress Dowager Cixi, who had been China’s de facto, but not official, ruler since 1861.[10] Increasing tensions between foreign residents and missionaries and the native Chinese, especially in Shandong province, characterised the final years of the 19th century, and were exacerbated by the devastation and desperation caused by the floods and various other natural disasters occurring at this time.[11]

RESPONSES

In the aftermath of the flooding, government funds were set aside in order to relieve affected areas, including a new emergency tax on wealthier locals in order to accrue money for aid. A missionary journal took the position that this was an attempt to show the benevolence of the Chinese government to the rural peasantry, in order to draw favour away from foreign missionaries and charitable organisations.[12] In terms of foreign aid, organisations such as the Baptist Missionary Society sent telegrams to their native countries to appeal to the public for subscriptions and other help.[13] A relief commission of 52 missionaries from Shandong and Henan Province, as well as various locations around the British Empire, was set up and raised a total of £5,413.17, £4,059 of which was used to relieve an estimated 78,000 people in Shandong. The majority of relief money was paid out to refugees in regular amounts in return for helping to repair damages.[14] Rather than money much of the relief sent from the United States consisted of corn, partly motivated by a desire to open up the food market in Asia to the west.[15]

CONSEQUENCES

The course of the Yellow River was permanently changed after the flood due to the seven-mile wide bank collapse near Jinan. The famine and destruction caused by the flood continued to increase dissatisfaction and desperation among the rural peasantry in Shandong province. Desperation created by the flood would be a major factor in the mobilisation of the provincial population against foreigners during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900.

Daniel Stone is a History undergraduate in the class of 2017 at the University of Manchester

NOTES

[1] Joseph W. Esherick, The Origins of the Boxer Uprising (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), p. 177.

[2] The Adelaide Chronicle, Nov. 19th, 1898.

[3] Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal, Dec. 1st 1898.

[4] The North China Herald, Nov. 7th 1898.

[5] The North American, Oct. 25th 1898.

[6] The New York Times, Mar. 25th 1899.

[7] The North China Herald, Nov. 7th 1898.

[8] The North China Herald, Oct. 10th 1898.

[9] Esherick, Origins of the Boxer Uprising, p. 179.

[10] Luke S. Kwong, A Mosaic of the Hundred Days: Personalities, Politics and Ideas of 1898 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 1984), p. 21.

[11] The New York Times, Jun. 24th 1900.

[12] The Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal, 1st Dec. 1898.

[13] The Morning Post (London), Nov. 9th 1898.

[14] The North China Herald, Sept. 12th 1900.

[15] The Washington Post, Feb. 26th 1899.