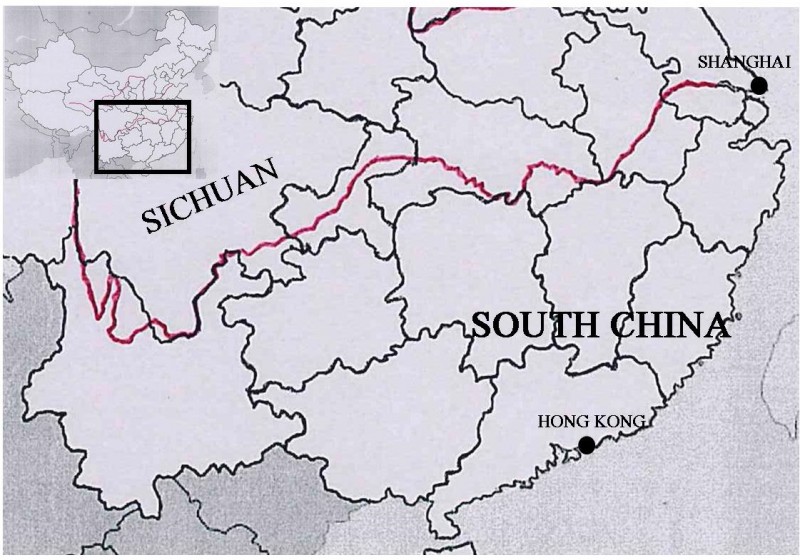

In the early spring of 1925, telegrams began to reach the China International Famine Relief Commission in Shanghai reporting the development of a major famine affecting more than 30 counties in Sichuan province 1,500 miles to the west.[1] With little surviving information on the scale of the disaster, it remains a relatively understudied episode in China’s history. Sichuan was just one of six provinces that in 1925 were reporting serious episodes of famine. Guizhou, Shaanxi, Zhili (today’s Hebei), Jiangxi and Hunan were all seeking immediate assistance from the Commission, while authorities in the province of Hubei informed central authorities of localized famine there.[2] The Sichuan famine of 1925 was part of an eruption of deadly disasters in 1920s China that coincided with the disintegration of the nation’s political system; in Sichuan especially, the famine was fuelled by the instability of China’s warlord era.

CAUSATION

Mortality statistics are notoriously difficult to attain in this period, both due to the chaotic political context and the lack of official census taking, and so estimates of overall deaths in 1925 Sichuan are often no better than guesses. One general history of the period puts total famine-related deaths in Sichuan in 1925 at more than 3 million people, but without citing relevant sources. [3] Surveys made by the Chinese and foreign relief organisations and philanthropists responding to the crisis are often the best estimates available. By June 1925, investigations by a province-wide relief society estimated that half a million people had already died in 80 afflicted counties (300,000 from starvation and 200,000 from disease) and more than 700,000 people had been displaced. [4]

One instrumental cause of the famine was the military power struggle that was plaguing Sichuan during the warlord era.[5] Military governors enjoyed an inordinate amount of control over provincial affairs and as such, they often ignored central government instructions and levied taxes to consolidate their own local sovereignty and power.[6] In the case of Sichuan, this type of political system was formed at the expense of the local population as a civil war broke out between rival warlords vying for leadership over the province.[7]

The foreign press in China reported that the famine was a combination of the effects of a provincial drought and poor rice yields exacerbated by local banditry and civil war that saw 40,000 troops moving about the province by the middle of 1925.[8] With local military officials prioritizing the provisioning of troops over feeding the local population, rice riots developed in Chongqing as soldiers consumed rice supplies at the major Yangzi river port in April.[9]

Adding to the exigencies and destruction of war, opium cultivation by farmers in Sichuan lowered the province’s overall food production.[10] By the mid-1920s, Sichuan was connected to the coastline of China by a series of roadways designed to improve the country’s internal trade. However, the high value crop of opium soon became practically the only crop that passed on these trade routes.[11] Due to the focus on opium production, the price of rice had tripled by May 1925, depleting household savings and leading to a surge in begging and the abandonment of children. [12]

RESPONSES

As a result of the chaos in Sichuan, the China International Famine Relief Commission (CIFRC) began mobilizing relief, supported by both the Chinese and foreign communities in China. In Shanghai, an initial 100,000 yuan was raised for the famine sufferers. Relief donations to the Commission’s efforts in Sichuan were also generated from major figures and individuals across China, including 2,000 yuan from the Panchen Lama to the people of the famine-afflicted provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou and Hunan.[13]

General Yang Sen was one of the most prominent of Sichuan’s warlords fighting for control of the province

Source: Wikipedia

Along with its campaign for charitable donations, the CIFRC launched relief operations, employing 32,000 people on famine relief distribution and flood prevention works in Sichuan by May 1925, a number that soon rose to 100,000.[14] The CIFRC was the largest single disaster relief organization in China since its founding in the wake of the 1920-21 North China famine. Underpinning the strength of the CIFRC was its ability to fuse the various aid cultures of its international personnel while drawing on resources from both the Chinese and foreign communities, making it instrumental in the organised responses to the 1925 disaster in Sichuan.[15]

CONSEQUENCES

Despite efforts to alleviate the affliction, famines continued to plague central and northern China for the rest of the 1920s and in the ensuing decades.[16] In Sichuan in particular, the military operations of the rival warlords delayed the relief programme as food and flood prevention mechanisms were unable to penetrate the areas that were most desperate.[17] Nonetheless, efforts were made by the CIFRC to not merely solve the short term crisis that affected northern and central China, but also to install methods of prevention that could ‘make flood and famine less likely in the future,’ through engineering works, credit-cooperatives, and skills training.[18] This included a programme to train over 40,000 people vulnerable to famine in the mat-making industry, which the Commission established in Zhili (today’s Hebei) province, providing a system that attempted to create long-lasting supportive measures.[19]

Internationally, however, the 1920s also saw a change in tone concerning China’s famines, as articles began to surface in the press overseas that created an image of the Chinese as weak, ignorant and ungrateful for international assistance received. By way of example, letter to the Washington Post in 1927 stated that ‘these famines China herself could alleviate if she had the honesty or the heart.’[20] Thus, while the internal reaction to China’s woes could be relatively positive, as highlighted by the efforts of the CIFRC that sought a collaboration from Chinese and foreign residents, some international commentators used the disasters of the 1920s to support a more negative viewpoint of a nation that remained at the mercy of western beneficence.

Luke Heselwood is a PhD student in Chinese Studies/History at the University of Manchester.

NOTES

[1] “The Triple Curse of China: Famine in Six Provinces the Result of Floods, Drought or Opium,” North China Herald (Shanghai)¸ 25 Apr. 1925.

[2] “The Triple Curse of China: Famine in Six Provinces the Result of Floods, Drought or Opium,” North China Herald (Shanghai)¸ 25 Apr. 1925.

[3] Michael Dillon, China: A New History, (London: I B Taurus, 2010), p. 202. The only source Dillon offers for 3 million deaths in 1925 Sichuan is a report from 1922.

[4] The figure of half a million deaths was reported midway in the crisis and presumably increased considerably over the year. Shenbao (Shanghai), 30 June 1925.

[5] “Famine relief: Tangible results during last year rural credit societies,” South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), 8 Jul. 1926.

[6] Edward A McCord, The Power of the Gun: The Emergence of Modern Chinese Warlordism, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), p. 308.

[7] “China’s Wars: Clash imminent in Szechuan, another assassination,” South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), 15 Apr. 1925.

[8] “Famine relief: Tangible results during last year rural credit societies,” South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), 8 Jul. 1926. See also, “Szechuan’s reply to the soldier: The New Militia, A Significant Movement, Yang Sen,” The North China Herald (Shanghai), Apr 25, 1925.

[9] “Szechuan’s reply to the soldier: The New Militia, A Significant Movement, Yang Sen,” The North China Herald (Shanghai), Apr 25, 1925. See also, Walter Mallory, China: Land of Famine, (New York: American Geographical Society, 1926), p. 164.

[10] “Famine relief: Tangible results during last year rural credit societies,” South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), 8 Jul. 1926.

[11] Carl Trocki, Opium, Empire and the Global Political Economy: A Study of the Asian Opium Trade, (New York: Routledge, 1999), pp. 124-125.

[12] ‘Severe Famine in Szechuan: Bitter Conditions Afflicting Whole Province: Help Earnestly,’ North China Herald (Shanghai), 23 May 1925.

[13] “Famine Relief for West China: The Shanghai Chinese: Foreign Famine,” The North China Herald (Shanghai), Aug 29, 1925. See also, “Panchem Lama and flood sufferers: Appeal to Nation to Aid Then Accompanying Gift,” The North China Herald (Shanghai), Oct 24, 1925.

[14] “The Triple Curse of China: Famine in Six Provinces the Result of Floods, Drought or Opium,” North China Herald (Shanghai)¸ 25 Apr. 1925.

[15] Andrea Janku, ‘The Internationalisation of Disaster Relief in Early Twentieth Century China’, in Mechthild Leutner and Izabella Goikhman ed., ‘State, Society and Governance in Republican China’ Chinese History and Society, Vol. 43, (2014), p. 9. See also, “Famine Relief for West China: The Shanghai Chinese: Foreign Famine,” The North China Herald (Shanghai), Aug 29, 1925.

[16] Dillon, China: A New History, p. 203.

[17] “Famine Relief for West China: The Shanghai Chinese: Foreign Famine,” The North China Herald (Shanghai), Aug 29, 1925.

[18] “The Triple Curse of China: Famine in Six Provinces the Result of Floods, Drought or Opium,” North China Herald (Shanghai)¸ 25 Apr. 1925.

[19] “Famine Relief for West China: The Shanghai Chinese: Foreign Famine,” The North China Herald (Shanghai), Aug 29, 1925.

[20] The Washington Post, 11 Feb. 1927.