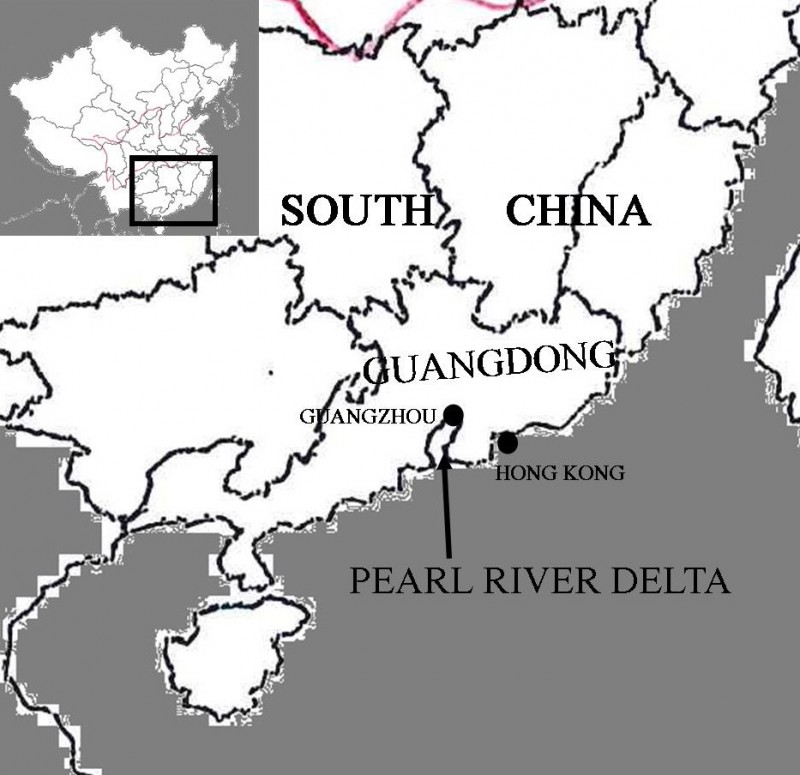

From mid-June until July of 1885 the Pearl River and its tributaries rose and caused huge flood damage in southeastern China’s Guangdong province after breaking through their embankments. With a death toll exceeding 9000 by the 31st of July, the inundation was reported by newspapers at the time as the worst seen in the region in thirty years. [1]

CAUSATION

On the night of 16th June, the calamity hit by surprise, leaving inhabitants little to no time to escape the rising waters, which in a few places reached 40 feet above normal levels.[2] As one article reported, “June was a month of violent and incessant rain. Day after day the deluges poured down unremittingly, saturating the soil and ruining the crops in all directions”.[3]

The flooding reportedly began in Tam Kong, near Fatshan (FóShān), when the embankments there gave way and continued as further embankments collapsed in Tai Wai, Lo Kap, Fung Lok and Shek Kok.[4]In addition, on the 25th June it was reported that the flooding was worsening as a result of the seasonal tides. As a result for approximately eighty miles around the provincial capital of Guangzhou, or Canton, the land was under water.[5]The lands surrounding the Pearl River in Guangdong were rice fields protected by embankments in some places as tall as 30 feet. The people living around the rivers dwelled mostly in villages ranging in population from a couple of hundred to several thousand and were highly dependent on the rice harvests. Aside from the villages there were district cities and trading towns each with populations in the tens of thousands. The buildings in these villages ranged in nature from mud hovels to brick houses but it is reported that even brick walls were not consistently able to withstand the floodwaters. In the lower reaches the river waters rising and breaking the embankments was the greatest danger to human life but in the higher regions it was the force of the water rushing down the mountain valleys that caught entire villages by surprise.[6]The situation was worsened by the impossibility of unloading the cargos on the region’s sampans, whose capsizing raised the number of those that drowned.[7]

An indirect cause of the distress was the international position of the Qing Empire. The Chinese government’s preoccupation with the fortification of the empire against external forces came at the detriment of reforms meant to bring ecological stability to settlements prone to natural disaster. Specifically, in the area of Canton, authorities reportedly showed little interest in the dredging operations required to remove build-up of sediment in the West River.[8]Meanwhile, the politico-military conflicts of the late 19th century had a profound effect on river control. During the Sino-French war (1884-1885), defensive measures blocked the outflow of the region’s waterways. In Tamkong, 14 miles from Canton, the barrier situated on the Pearl River constructed to keep the French out interfered with the natural run off from heavy rains. When the dyke system succumbed at several points, water was given free reign over adjacent lands, bringing more distress.[9]The torrent of the inundation was so strong that in certain points it carried away the dikes, and at Sz-Ni city, the city wall crumbled, leading to the drowning of thousands of inhabitants.[10]

One report from a missionary aid party states that in the 42 villages they visited 2 084 houses had been destroyed and around 9 000 individuals were in distress. The missionary group also reported widespread sickness, chiefly fever and skin diseases, presumably as a result of malnutrition and lack of shelter.[11]In terms of damage to specific districts and areas it is difficult to gauge the exact extent of the damage and loss of life. The newspapers themselves claim that the “information on the subject is vague” but seem to agree that at least eleven large districts were severely affected. A report from district magistrate Po Wan Kok details the effects of the flooding on Sam Shap Luk Heung (Sānshíliùxiāng), where he claimed that twenty-eight villages of the thirty-six in the district had been entirely swept away including 2 000 shops and houses leaving 50 000 people homeless.[12]Similar reports from the Tsing Un and Kwong Ning magistrates tallied 150 000 and 5 000 people in distress in their respective districts.[13]

RESPONSES

It appears that most of the relief provided to the people affected by this calamity came from foreign missionaries and a number of hospitals in the Pearl River delta area. The missionary newspapers detail their own party expeditions and also praise the Oi Yuk Shin Tong, a hospital in Guangzhou, and the Tung Wah Hospital in Hong Kong. These Chinese organisations sent steam launches upriver to bring aid to those in need as a result of the inundations. It is noteworthy that the steam launches were instrumental in bringing relief as conventional crafts could not navigate upstream in such extreme conditions and certainly could not when bearing sufficient emergency supplies. The missionary parties themselves apparently visited over 350 villages and distributed 3 400 piculs of rice and $1 000 worth of biscuits. This roughly distributed 6 catties of rice to each person, approximately 3.6kg per person, from only the missionary parties though it must also be remembered that these parties did not reach all affected areas.[14]The Chinese hospitals in Guangzhou and Hong Kong continued to provide aid after the floodwaters subsided providing further food supplies and medical aid to affected villages.

The Qing government offered employment to the men that were affected by the flood in repairing the dams, reallocating some to other districts, and assisted the planting efforts of local farmers.[15]Later that year, the government determined that its dispatching of 30,000 taels (silver ounces) was insufficient for relief, and upfronted a request for 10,000 more.[16]

CONSEQUENCES

The damage to the rice fields was immense; reports say that villages near the rivers were entirely swept away and vast areas of crops were destroyed. As a result of the huge loss of rice crops the price of rice is reported to have risen by 18% in Shanghai.[17]Not only was the rice lost but the fields themselves were under six feet of sand. The damage to the rice fields not only had the immediate effect of destroying the current harvest but also, due to the sand, made the fields unusable so the following harvest became delayed. It was reported that along the river from Wai-tsap, a village near the border with Guangxi Province, to Sam Shui (Sānshuǐ), in Foshan, the rice crop was entirely destroyed. [18]In addition to the loss of rice crops the silk crops were also heavily damaged but the reports on this were less detailed presumably due to the fact that it posed a less immediate dilemma.

Elisa-Andreea Linu contributed writing and research to this article. Christopher Yien (Chinese Studies) and Elisa-Andreea Linu (History with Economics) are undergraduates in the class of 2019 at the University of Manchester.

[1] ‘Serious Floods at Canton’, The North China Herald and Supreme Court and Consular Gazette (Shanghai), 3 July 1885, 12.

[2] H. V. Noyes, `Floods in Kwangtung: Before the flood’, The Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal (Shanghai), 1 October 1885, 374.

[3] ‘The Weather and the Floods’, North China Herald, 10 July 1885, 34.

[4] ‘Terrible Flood in China’, Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney), 29 August 1885, 450.

[5] ‘Serious Floods at Canton’, North China Herald, 3 July 1885, 12-13.

[6] ‘Floods in Kwangtung’, Chinese Recorder, 1 October 1885, 375-376.

[7] `Serious Flood at Canton’, North China Herald, 3 July 1885, 12.

[8] `The floods in China’, The Scotsman (Edinburgh), 4 December 1885, 7.

[9] `The floods in China’, The Scotsman, 4 December 1885, 7.

[10] `Serious Flood at Canton’, North China Herald, 3 July 1885, 12.

[11] ‘The Floods in Kwangtung’, North China Herald, 31 July 1885, 130.

[12] ‘The Kwangtung Inundations’, North China Herald, 17 July 1885, 69.

[13] ‘Floods in Kwangtung’, Chinese Recorder, 1 October 1885, 375.

[14] ‘Floods in Kwangtung’, Chinese Recorder, 1 October 1885, 376.

[15] H. V. Noyes, `Floods in Kwangtung: Before the flood’, Chinese Recorder, 1 October 1885, 374.

[16] `Abstract from Peking Gazette’, North China Herald, 21 October 1885, 466.

[17] `Serious Flood at Canton’, North China Herald, 3 July 1885, 13.

[18] ‘The Floods in Kwangtung’, North China Herald, 31 July 1885, 130.