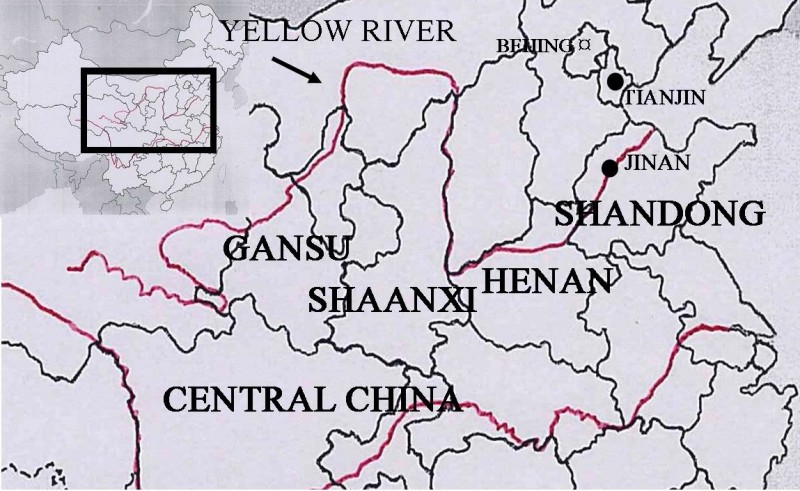

Starting in early 1928, warfare and drought disaster across northern China reached their destructive peaks, culminating in severe famine in roughly 300 counties. First affecting coastal Shandong Province, and then shifting northwest to inland Henan, Shaanxi and Gansu, millions faced a natural disaster that would plague northern communities for three years. Despite limited local and international relief efforts, the Northwest famine of the late 1920s rivals the North China Famine of 1876-1879 as the most devastating natural disaster in modern Chinese history.

CAUSATION

The failure of crops in Shaanxi’s fertile Wei River Valley was a main ‘spark’ in triggering food shortages in China’s Northwest, with drought rendering 9.2 million acres of arable land barren.[1] Nonetheless, the famine that ensued was more political than natural in origin.

Famine conditions were exacerbated by simultaneous military activity in the area. Warlords had already established the foundations of famine, stripping counties ‘ruthlessly’ of grain, livestock, and farming implements.[2] Their demands for the people to plant opium for their economic gain also helped catalyse the famine, cultivable food-producing areas reduced to opium plantations.[3] Subsequent conflict accelerated and intensified the effects of famine, causing mass upheaval in Northern China. Further causing and catalysing such effects was the lack of participation the Chinese National Government had in defence and relief schemes. Preoccupied with military conflict, various levels of government neglected dam and dike maintenance, increasing the likelihood of famine conditions, while food-production decreased massively in the prioritising of supplies to soldiers over the workforce. Indeed, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions reported that “several cases of cannibalism” had been confirmed in the desperation of sustenance.[4]

Millions living in the Wei River Valley initially affected by famine abandoned their province in search of better conditions. Manchuria in China’s Northeast experienced an influx of 4 million refugees, and the city of Jinan in coastal Shandong Province saw 25,000 refugees ‘existing on only one bowl of free gruel daily.’ On top of Shaanxi’s 3 million deaths by hunger and disease, 6 million people fled.[5]

Due to sketchy and incomplete data, estimates for the famine’s overall death toll ranges anywhere from 3 to 10 million people.[6] In place of official statistics, which the region’s warring military regimes often neglected to collect, the Famine Relief Commission estimated that 4,000,000 had been reduced to beggary,[7] while a major newspaper claimed that “thousands die[d] daily” in the famine.[8] Famine-based casualties showed no signs of decreasing, a further 2 million expected to die between January and June as late as 1930.[9]

RESPONSES

News of widespread famine in China’s Northwest elicited substantial relief efforts from around the country, and from international channels. In 1929, the Chinese-Foreign Famine Relief Committee distributed $382,000 to fund relief work from affected regions from Gansu to Jiangsu. It also confirmed additional payments of $75,000 and $36,000 in 1930 to the innermost provinces of Gansu, Shaanxi and Henan.[10] Furthermore, projects were funded to “make nature help herself,” notably one developing drought-resistant seeds for Chinese farmers. By 1930, the North China Mission had given $6,000 towards making such seeds increasingly available to farmers nationwide. Thousands of Chinese responded, many establishing charity kitchens and offering basic accommodation for migrants.[11]

CONSEQUENCES

Efforts to send aid in response to the Northwest Famine were only beneficial in providing short-term relief, and even then, financial aid could only prop-up provinces, not offer a long-term solution to famines and subsequent disasters. Even in 1932, droughts, floods and plagues were reported as being “more frequent in the North and Northwest” than ever before.[12] Much relief never saw those it was intended to aid, the campaigns led against warlords Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan by Chiang Kai-Shek severely disrupting trans-Chinese commerce; and the execution of ‘scorched-earth’ tactics and disruption of rail traffic destroying the remaining arable land, making essential provisions especially harder to transport.[13] Drought-proof seeds were not an immediate solution. The elusive but undeniably catastrophic death-toll of the famine exemplifies how ineffective the aid was at saving lives, with possibly 10 million of 57 million residents killed.[14] However, this is not to suggest all relief-efforts were ineffective. Newspapers in 1931 report a $1,000,000 canal-building project from the King River to Shaanxi Plain, limiting the effect of drought in some areas in the years ahead.

Hal Baldwin (History) is an undergraduate in the class of 2018 at the University of Manchester.

NOTES

[1] ‘Famine Prevention’, Chinese Recorder, 1 February 1930.

[2] ‘Famine in China’, South China Morning Post, 20 January 1930.

[3] ‘Refutation of Northwest Militarists’ Manifesto’, China Weekly Review, 19 October 1929.

[4] ‘Tells of Famine Horrors’, New York Times, 7 July 1929.

[5] Li, Lillian, Fighting Famine in North China, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), p. 304.

[6] Li, Fighting Famine, p. 304.

[7] ‘Children Sold by Chinese Parents’, Daily Telegraph, 21 January 1928.

[8] ‘Thousands Die Daily’, New York Times, 23 February 1929.

[9] ‘Famine in China’, South China Morning Post, 20 January 1930.

[10] ‘Chinese-Foreign Famine Relief Work’, China Weekly Review, 22 March 1930.

[11] ‘Famine Prevention’, Chinese Recorder, 1 February 1930.

[12] ‘Flood Reconstruction’, North China Herald, 5 January 1932.

[13] ‘Famine in China’, South China Morning Post, 20 January 1930.

[14] Li, Fighting Famine, p. 304.