In spring 1936, reports of drought and starvation in Sichuan began to appear in the press in China and overseas.[1] By the following year it was being reported that two thirds of the countryside in the normally fertile province had turned to ‘hard, grassless clay’,[2] while according to a survey of the Szechwan Famine Relief Commission 30 million people were affected in 140 out of 149 hsien (districts) in the province.[3] Reports also tallied 50 million ‘famine refugees’, although some may have been the result of civil war.[4] Rains finally arrived in April 1937, although many people remained starving, and press and government attention to the province and its plight was yet to peak.[5] One general history of famines worldwide offers an estimate of 5 million human famine-related deaths in 1936-37 Sichuan, although the basis for such a figure is unclear. Millions of deaths out of the estimated 30 to 50 million afflicted from famine in Sichuan in 1936-37, however, is not unlikely. [6] Drought-famines occurred at the same time in Henan, Shaanxi and Gansu provinces.

CAUSATION

While fertile and densely populated, Sichuan was economically backward.[7] The province had seen 100 civil wars since 1911 and taxed its farmers heavily and up to 80 years in advance, leaving farmers to live on the very margins of existence.[8] A report in April 1937 said that the drought centred in the ‘northeastern portion of the extreme northwestern portion of the province’, and that 9 counties lost 2/3–4/5 of their crops in 1936, 30 hsien lost 40-50%, while another group of counties lost ‘some’ crops.[9] The province had poor transport links to the rest of China,[10] which was exacerbated when low tide on the Yangzi prevented food from reaching the province.[11] The Shanghai-based foreign news daily China Press downplayed any role of communist insurgency in the crisis, stating only that the drought occurred ‘in the wake of communist disturbances and natural calamities’[12]

The famine, and the disorder it bred, occurred in a fragile political balance with fighting between communists and nationalists and between provincial and national authorities. The China Press, for example, reported that the riots and displacement of population ‘constitute a constant menace to peace and order’ and urged government help.[13]

It should be noted that the New York Times was sceptical of the famine reports, arguing that what had been reported in the province was ‘merely a normal condition which has become somewhat exaggerated’. While acknowledging the drought in early 1937, as well as the precariousness of peasant livelihoods in Sichuan, the paper argued that famine reports were built from only ‘fragmentary evidence’ and that ‘it is not on record that any official has urged the sending of grain into his special district. But all of them plead that money be sent so that they can purchase grain.’[14] However historians now record a famine as having occurred in Sichuan. According to Cormac O’Grada the ‘1936 famine, the product of severe drought compounded by civil war, killed up to five million people in Sichuan and led to reports of widespread cannibalism.’[15]

CONSEQUENCES

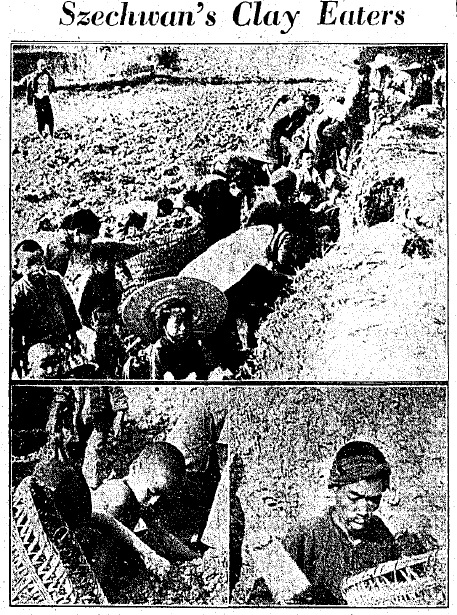

The population were reported to have made a variety of desperate attempts to survive. In March 1937 the New York Times reported widespread prayer for rain by the afflicted population.[16] Newspapers widely reported that ‘bark and grass were the only succor of many sufferers. Snatching of foodstuffs by despairing victims is almost a daily occurrence. Often in these riots, the casualties ran to several scores.’[17] Riots also featured in the American press coverage, including a report of ‘800 hunger-crazed farmers attacking rice junks’ at Yongchuan, near Chongqing. It was suggested that riots occurred in nearly every section of the province and that the starving had ‘raided rice shops, kidnapped children to sell them for food and eaten the leaves off trees.’[18] In eastern and central parts, parents were seen ‘tossing their children into the streets to die.’[19] Missionaries reported refugees eating ‘Fuller’s earth’ and that some were ‘digging out an oil-bearing shale, which they stated they were mixing with tree-bark, green weeds and a little kaoliang for food.’[20] As well as stories of hardship, photographs were published in the press and shown in Shanghai theatres to elicit sympathy and donations (see below).[21]

Famine sufferers in Sichuan digging below the dry surface of the soil for moist clay and roots underneath to eat, along with other so-called “famine foods.”

Source: The China Press (Shanghai), 10 June 1937.

RESPONSES

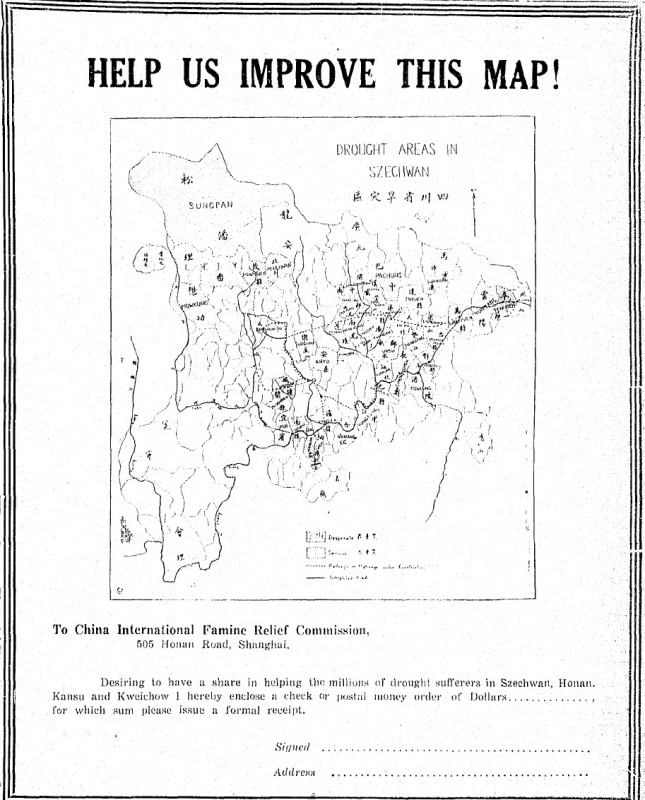

Public and private funds came from a variety of sources as the famine gained prominence in the national consciousness and began to affect the politics of the region. In the tradition of native-place associations, Sichuanese in Nanjing and Shanghai made particular efforts to rally support and raise funds.[22] Overseas philanthropist Hu Wen-hu sent $10,000 through the Bank of China,[23] while diaspora communities in Japan and the Philippines sent similar amounts for the relief funds.[24] Foreign missionaries offered some help[25] and a Polish Bishop sent 1,000 Zloty.[26] Demonstrating a mix of Chinese agency and internationalist ideas, the National Child Welfare Association was formed to raise funds from the public for famine orphans, using press and fundraising in schools. It opened a number of homes in Sichuan and other districts, and was based on the principle, articulated at in the Declaration of the Rights of the Child in Geneva, that children should receive relief first.[27] The China International Famine Relief Commission (CIFRC), jointly set up by westerners and elite Chinese in 1921, also garnered a lot of press attention, with its president, John Earl Baker, described as an ‘ace famine fighter…swinging into action’ in tours in the famine regions.[28] The body was well-linked with the national government and leading financial centres and in May 1937, with the help of the vice president of the Executive Yuan raised a $300,000 loan from three government banks.[29]

Relief measures included emergency relief, labour relief, small loans for farmers, subsidized food and free food.[30] The CIFRC, for example, entered into an agreement with the West China Development Corporation whereby famine victims would be given preference in hiring for railway building, and the CIFRC would construct several earthworks. They also made an agreement with the Salt Administration for highway building as a means of work relief.[31] The relief was delivered in the context of the National Government’s desire to exercise greater political and military control over Sichuan.

A relief fundraising appeal in the English-language press in Shanghai in spring 1937.

Source: The China Press (Shanghai), 15 May 1937.

Money was forthcoming from the beginning and in March 1936 the ‘Szechwan provincial government…ordered the Provincial Department of Finance to appropriate $100,000 immediately for urgent relief.’[32] By April 1937, it had raised over $14m: $6.5m for exemption of the farm tax in drought districts, $4.8 for road construction by refugees, $1m for small credit loans ($20 each) for peasants and $2m to buy rice from other provinces to stabilise prices.[33] Nanjing’s help was also called for and in March 1937, Liu Hsiang, chairman of the Sichuan provincial government, asked for $5,000,000 from the National Government.[34] Indeed, some difficulty was reported over the security for a government-backed loan.[35] However, ‘prospects brightened’ for the flotation of bonds to relieve the famine when an envoy of Hsiang pledged loyalty, stating that the Sichuan authorities were willing to hand over all military and political power to the National Government.[36]

Prominent members of the Nanjing government used the famine to assert their compassion, efficacy and authority. Press reports noted their fact-finding trips, such as a General Chu, chairman of the National Relief Commission, arriving in Sichuan greeted by a military band before touring the famine areas.[37] A temporary committee was also organised by Chiang Kaishek’s provisional headquarters in Chongqing. All staff members were to donate a certain proportion of their salary, with those above Major-General giving 20%, above Lieutenant-Colonel 10%, lower ranks 3-5% and soldiers 10 cents.[38]

The relief effort was also couched as part of efforts to develop Sichuan’s economy, infrastructure and governance. The Szechwan Famine Rehabilitation Research Committee used the famine to petition the government for an end to opium cultivation and ‘oppressive taxes’, often levied 70 or 80 years in advance, which had ‘drained’ the province ‘to the bone.’[39] Nevertheless, the China Press was sanguine about the prospects of modernisation since the communists had been driven away, reporting on the ‘new deal’ begun by General Liu in 1935, including investments in education, construction of a Chengdu-Chongqing railway, a Sichuan Water Conservancy Commission and a Rice and Wheat Improvement Station.[40] Similarly, the Institute of Pacific Research, a Rockefeller-funded NGO, reported on the province after the famine, urging modernisation and expressing the question-begging hope that ‘the famine will teach the farmers the benefits of using drought-resisting seeds.’[41] Railways and roads were touted as a way to improve the fortunes of Sichuan,[42] and Chiang Kai-shek announced regulations ‘for the construction of dams, canals and ponds as a permanent solution for the famine in Szechwan.’[43]

Luke Kelly graduated with a PhD in History from the University of Manchester in 2013.

NOTES

[1] ‘South Honan Hard Hit By Flood Ravages: Northern Szechwan in Grip of Spring Famine,’ The China Press, 30 March 1936; ‘Millions Die in Record China Drought Famine,’ Los Angeles Times, 11 July 1936. The same report was printed in the New York Times.

[2] ‘Famine in two provinces: Reports from China’ Manchester Guardian, 17 March 1937.

[3] ‘On Verge of Starvation,’ The China Press, 20 March 1937; “Plans Adopted To Push Drive For Szechwan,” The China Press, 18 May 1937. Other reports estimated there were 35 million famine-afflicted. Shenbao (Shanghai), 29 April 1937.

[4] ‘Wu Ting-Chang, Back From Szechwan, Urges Prompt Famine Relief,’ The China Press, 7 April 1937.

[5] ‘Chinese drought broken: Heavy, Widespread Rains Fall In Central Section,’ Baltimore Sun, 9 April 1937.

[6] Cormac O’Grada, Eating People is Wrong, And Other Essays on Famine, Its Past, and Its Future (Princeton, 2015), 138.

[7] Cormac O’Grada, Famine: a short history (Oxford, 2009), 251-252.

[8] ‘The Plight of Szechwan,’ The China Press, 26 June 1937.

[9] ‘Baker Returns From W. China Famine Study: Million People Said Seriously Affected,’ The China Press, 24 April 1937.

[10] Jonathan Spence, In Search of Modern China (London: 1999), 431.

[11] ‘Szechwan Relief Group Being Organized Here: Provincial Natives Sponsor Association,’ The China Press, 10 April 1937.

[12] ‘Wu Ting-Chang, Back From Szechwan, Urges Prompt Famine Relief,’ The China Press, 7 April 1937; ‘Szechwan’s “New Deal” Described In Nanking,’ The China Press, 22 March 1937.

[13] ‘Wu Ting-Chang, Back From Szechwan, Urges Prompt Famine Relief,’ The China Press, 7 April 1937.

[14] ‘Szechwan Hunger is Found Normal,’ New York Times, 11 July 1937.

[15] O’Grada, Eating People is Wrong, 138.

[16] ‘10,000,000 starving in China’s drought,’ New York Times, 29 March 1937.

[17] ‘On Verge of Starvation,’ The China Press, 20 March 1937.

[18] ‘Rioting Hungry Farmers Shot By Chinese Troops,’ Baltimore Sun, 25 March 1937. The same article was printed in the New York Times.

[19] ‘Children Left to Die in Street,’ Los Angeles Times, 14 April 1937.

[20] ‘Baker Returns From W. China Famine Study: Million People Said Seriously Affected; Relief Plans,’ The China Press, 24 April 1937.

[21] ‘Corpses Being Stolen, Eaten In Famine Area,’ The China Press, 10 June 1937.

[22] ‘Szechwan Relief Group Being Organized Here: Provincial Natives Sponsor Association,’ The China Press, 10 April, 1937; ‘Relief Sum Obtained On Kung Order Earmarked,’ The China Press, 21 May 1937.

[23] ‘Dr. John E. Baker Proceeds to Szechuen to Discuss Famine Relief,’ The China Weekly Review, 17 April, 1937, 264.

[24] ‘Chinese Residents in Osaka Contribute $12,500 to Drought Relief,’ and ‘Sir Robert Hotung Donates Another $50,000 for flood relief—is entertained at reception,’ The China Weekly Review, 3 July 1937.

[25] ‘Famine relief in Szechuen,’ The Chinese Recorder, 1 September 1937.

[26] ‘Polish Bishop Aids Szechwan: 1,000 Zloty Sent To Help Refugees,’ The China Press, 20 June 1937.

[27] ‘Drive Starts To Relieve Famine Areas,’ The China Press, 18 April 1937; ‘Children Asked To Give For Child Welfare,’ The China Press, 7 June 1937.

[28] ‘Dr Baker leaves today to direct relief in Szechwan,’ The China Press, 9 April 1937.

[29] Relief Sum Obtained On Kung Order Earmarked,’ The China Press, 21 May 1937.

[30] ‘Concrete Plans Decided On For Famine Relief: Emergency Fund Set Up; Labor Relief Money Provided,’ The China Press, 21 April 1937.

[31] ‘Baker Paints Bleak Picture Of Dry Areas,’ The China Press, 7 July 1937.

[32] South Honan Hard Hit By Flood Ravages: Northern Szechwan in Grip of Spring Famine,

The China Press, 30 March 1936.

[33] ‘Chu Back, To Push Szechwan Relief Efforts: leaves For Nanking To Discuss Local Question,’ The China Press, 17 April 1937.

[34] ‘On Verge of Starvation,’ The China Press, 20 March 1937.

[35] ‘Ministry Turns Down Proposal Of Relief Loan: $15,000,000 Szechwan Issue Rejected As Impractical,’ The China Press, 29 April 1937.

[36] ‘Liu Hsiang Sends Envoy To See Chiang: Tension Over Szechwan Situation,’ The China Press, 23 May 1937.

[37] ‘Chu Arrives In Chungking On Relief Mission,’ The China Press, 20 April 1937.

[38] ‘Rain Proving Real Godsend For Szerhwan: Chengtu Official In Sian, Reports On Situation,’

The China Press, 3 May 3 1937.

[39] ‘The Plight of Szechwan,’ The China Press, 26 June 1937. The paper said it was ‘not informed’ of the composition of the committee.

[40] ‘Szechwan’s “New Deal” Described In Nanking,’ The China Press, 22 March 1937.

[41] William Lee, ‘Vast Change In Szechwan, Carter Finds,’ The China Press, 29 May 1937.

[42] ‘Railways and roads to ease famine: Salt Administration to Start $500,000 Project,’ The North – China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette, 14 July 1937.

[43] “Irrigation Projects Will Ease Szechwan Drought Situation,” The China Press, 20 May 1937.